11 Jan Perspective: Western Revelry

Born in 1925 and raised on the Gulf Coast in the small oil town of Port Arthur, Texas, Robert Rauschenberg matured into an internationally influential artist and a citizen of the globe. Known to his friends as Bob, he may never have visited the Denver area where the Museum of Outdoor Arts (MOA) is exhibiting Rauschenberg: Reflections and Ruminations through March 20. He did, nonetheless, enjoy a robust connection to the American West.

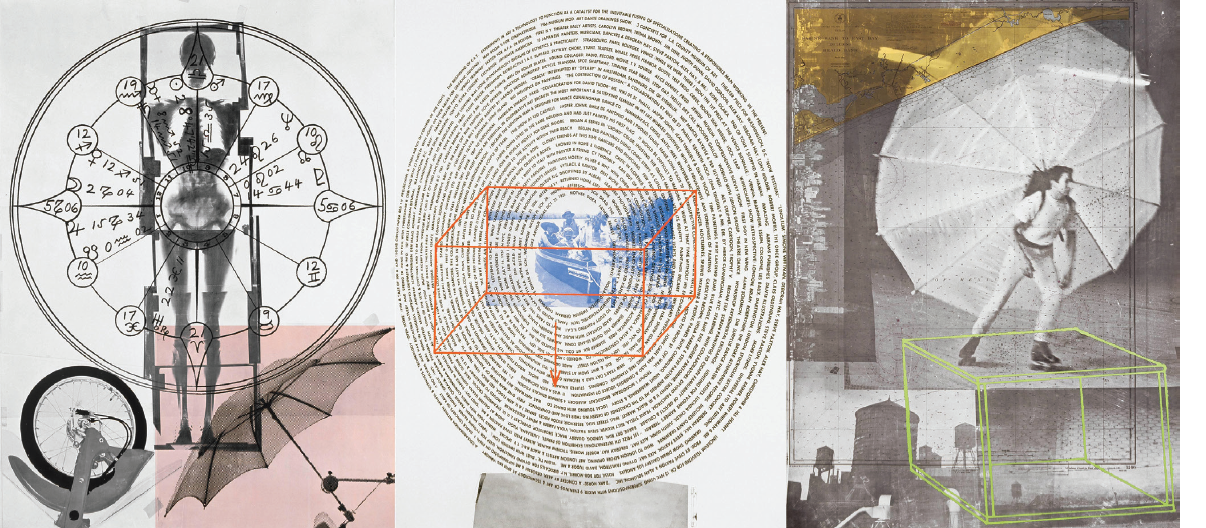

Windward Series VIII |Acrylic, Solvent Transfer, and Graphite on Paper | 1992 | Private Collection | Photo Courtesy of MOA | Windmills appear prominently in Rauschenberg’s work, perhaps reflecting the artist’s attraction to the dynamism of the spinning blades. Tires, wheels, clock faces, and bicycles are used in a similar fashion in several examples seen throughout the MOA exhibition in Denver. Collectively, they can be viewed as reflections of Rauschenberg’s interest in machinery, his fascination with travel and motion, and an overarching interest in the passage of time.

“Rauschenberg is an autobiographical artist,” says the exhibit’s co-curator, Dan Jacobs. “He embodied the West Coast spirit. He was not a New York artist, though he was shown in New York galleries when he was in his 20s — but he was not seduced by that success. Rauschenberg had Western cool.”

Co-curator Sarah Magnatta adds, “Rauschenberg was an East Coast radical, taking risks. He was non-establishment. He saw everything in a fresh way and forced us to ask, ‘What is high art? What is low art?’”

Robert Rauschenberg at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, April 1968, with his artwork.Photo source: Nationaal Archief, CC0 | Photograph by Jac de Nijs / Anefo

The MOA show includes numerous nods to Rauschenberg’s connection to the West. A case in point: In Autobiography, his spiral timeline installed in the Englewood Civic Center lobby just outside MOA’s doors, Rauschenberg noted Camp Pendleton in San Diego, California, where he was stationed while serving in the U.S. Navy. In Opal Gospel, a tabletop interactive book of sorts made of silkscreen ink on Plexiglas sheets, Rauschenberg incorporated texts derived from the oral traditions of Native American tribes out West, including the Navajo, Pawnee, and Apache.

Rauschenberg mixed media, blended genres, and demolished pigeonholes that separated photography, painting, sculpture, found objects, and performance arts. He famously erased a Willem de Kooning drawing and went on to create white paintings as the maximal minimalism.

But Rauschenberg is perhaps most highly esteemed as an innovative printmaker. He designed the first Earth Day poster in 1970. The MOA show exhibits a range of exuberant Rauschenberg prints, and some of them were produced at Gemini G.E.L. (Graphic Editions Limited) in Los Angeles.

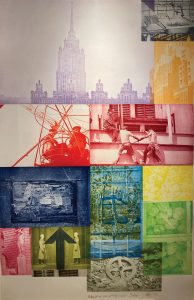

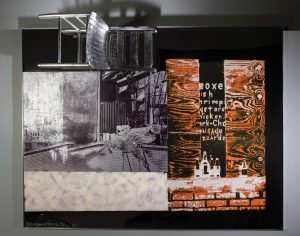

Soviet/American Array VII | Photogravure | 1991 | Collection of Carol and Henry Goldstein | Photo Courtesy of MOA In many of the prints shown during the USSR leg of Rauschenberg’s international exhibition tour, he combined images from the U.S. and Russia, documenting everyday scenes from the two major Cold War powers just as that period was coming to an end. A believer in the unifying power of the arts, he featured the similarities between the two cultures more than the differences.

The exhibition features works from Colorado collections, both public and private. One of the quirky showstoppers, Pegasits, features a winged horse printed on stainless steel and a 3-D wooden chair covered in silver leaf. The piece is on loan from the Madden Collection at the University of Denver, donated by John W. Madden Jr.

The Madden Collection also loaned Ileana, an intaglio print, and Eagle Eye, a photolithograph, both from Rauschenberg’s Ruminations series. A retired developer and longtime patron of the arts, Madden and his daughter Cynthia Madden-Leitner co-founded MOA in 1981. Madden came by his Rauschnbergs directly, having befriended the artist in Captiva, Florida, a small island where they both owned homes.

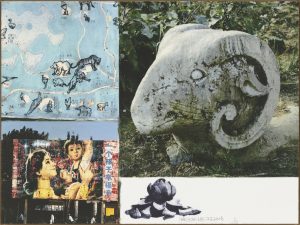

Lotus X, from the Lotus Series | Ink-Jet with Photogravure | 2008 | Collection of the Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) | Photo Courtesy of MOA In his final print series, Rauschenberg presented the lotus as an enduring symbol of meditation, tranquility, and reflection. The photographs were mostly taken during his groundbreaking art-making collaborations in China more than two decades earlier.

When Rauschenberg attended a Christmas party at the Maddens’ home, Madden-Leitner, like most people who met the charismatic Rauschenberg, was charmed. A fan of his art, she subsequently traveled to Italy and New York City for two of the artist’s major exhibitions, all the while envisioning a Rauschenberg exhibition at MOA.

Like Rauschenberg himself, she collaborated, connecting the dots between her contacts in the art world. MOA hired the co-curators, and Jacobs and Magnatta brought their impressive academic pedigrees, each with stretches at both the Denver Art Museum and the University of Denver. The curators followed trails and discovered Rauschenberg connections in Colorado.

The MOA show includes two Rauschenbergs on loan from the University of Colorado (CU) Art Museum. Hog Chow, a 1977 screenprint on paper with collage, is from an edition of 100 and is part of Rauschenberg’s Chow Bags series. Sketch for Monogram, a lithograph and screenprint, was a gift from Rauschenberg to the CU Art Museum. In addition, Colorado collectors Carol and Henry Goldstein loaned their Rauschenberg titled Soviet/American Array VII.

The artworks in the MOA exhibition depict popular culture, pets, friends, and parts of the artist himself, such as his skeleton X-ray and handprint. The artist’s personal life was almost as colorful as his artworks.

“Like Picasso or Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg is one of those artists whose personal life gets almost as much limelight as his art,” says Madden-Leitner.

Speaking in Tongues | Printed Translucent Vinyl LP Record with three Printed, Translucent Plastic Inserts and Clear Plastic Album Cover | 1983 | Private Collection | Photo Courtesy of MOA In 1983, Rauschenberg designed a translucent special edition LP of the Talking Heads’ hit album, “Speaking in Tongues.” By designing an element that could be mass-produced and purchased by thousands of consumers, Rauschenberg brought the concept of collaborative art directly into audiences’ homes.

Rauschenberg’s biography reads like a “who’s who” in American arts. In the 1950s, on the GI Bill, he attended Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he met two of his closest creative friends: the composer John Cage and the artist Jasper Johns. He also collaborated with the dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham and many others.

Rauschenberg was one of the rare American artists who was a household name during his lifetime. He used his significant influence to bridge not only media but also nations.

“Rauschenberg was an international pioneer,” says Nora Burnett Abrams, the Mark G. Falcone Director for the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver (MCA). “Just as you can’t contain his work in painting or sculpture or stage design or costumes, you can’t connect him to any one place.”

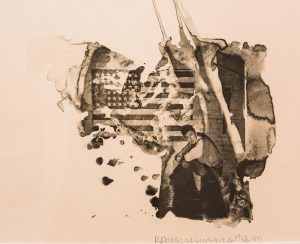

Jap, from the Ruminations Series | Photolithograph on Paper | 1999 | Madden Collection at the University of Denver | Photo by William O’Connor Rauschenberg often reflected on photographs and souvenirs of his early life. Jap features an image of well-known American artist Jasper Johns, who Rauschenberg endearingly called “Jap” for short. Having met Johns while attending Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the early 1950s, the two artists later had a close relationship and lived in adjacent apartments in New York City, where they experimented and exchanged ideas in the 1950s and ‘60s. Both were instrumental in pushing the art world out of Abstract Expressionism and into figural representation.

Under the aegis of the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange (ROCI) — pronounced “Rocky,” the name of the artist’s pet turtle — the artist made groundbreaking trips as an art ambassador. He went to China, where he worked at the Xuan paper mill — one of the oldest in the world. He traveled to Africa and Japan. In Russia, he met with President Mikhail Gorbachev. In Cuba, he stayed at President Fidel Castro’s beach house. He enjoyed the hospitality of Malaysian headhunters, spent a week with the Dalai Lama, and rubbed elbows with a cross section of luminaries and celebrities, including Hilary Clinton, Elizabeth Taylor, Mohammed Ali, Lauren Hutton, Lily Tomlin, and Sharon Stone. Rauschenberg happened to be in Berlin when the wall came down. Everywhere, whether at a mansion or a junkyard, Rauschenberg gathered information and inspiration. “Rauschenberg was a visual anthropologist,” Jacobs says. “He was a sponge for visual culture.”

The MOA show displays Rauschenberg’s affinity for the circle. In addition to the spiral of his timeline, his works show the roundness of bicycle wheels, automobile tires, windmills, waterlily pads, clock faces, umbrellas, gears, a spherical ball of twine, and LP records. Rauschenberg’s sculptural printed discs and plates figured into several of his large-scale works.

Pegasits | Acrylic, Fire Wax, and Chair on Stainless Steel | 1990 | Madden Collection at the University of Denver | Photo by William O’Connor Pegasits is one of many works in which the viewer becomes part of the art, which is essentially a giant mirror with painted and printed areas. The title refers not only to the mythical winged horse Pegasus (shown here as the familiar emblem of Mobil Oil), but also to the simple chair soaring overhead.

The artist had a wide circle of friends and cast his benevolent net even wider through his philanthropy. A person remembered well for his joie de vivre and fearless innovation, he’s lionized as one of America’s most influential artists.

Rauschenberg: Reflections and Ruminations showcases more than 50 works created from 1962 to 2008, the year of the artist’s death on Captiva Island in Florida, where he’d lived since the 1960s and died at age 82, another full circle drawn.

No Comments