12 May Rendering: A Collective Effort

Steve Bull can’t recall a definitive moment or event that led him to architecture. There was no childhood epiphany over a set of building blocks; architecture was simply the course his life took, and nothing, from his undergraduate studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to real-world jobs, ever dissuaded him.

When Bull opened his firm, Workshop AD, in 2004, he worked alone in a 250-square-foot space in Seattle’s downtown Pioneer Square. He had what he describes as the classic architect’s start: doing small projects for friends. Within months, he was able to bring on senior associate Dan Rusler, and over the years, the firm has won numerous awards and grown into a team of 10.

From the beginning, Bull’s vision was for the firm to be a collaborative endeavor, and naming it after himself was not a consideration. But beyond the idea of generating a collective design voice from disparate backgrounds and experiences, Bull saw the workshop as equally dedicated to craft and materials, and their context within a project’s environment. To explain, he conjures up a mental image of a metal or woodworking shop, where the shavings and dust generated by apron-clad craftsmen are reflected in shafts of light.

“It’s our hope that our approach to our work reflects an understanding of how and why we make things,” he says, “both through the design process and, ultimately, the structures and spaces that process leads to. Along the way, we study the nature of the materials and how they come together to express a qualitative intention for the spaces we build.

“When I taught at a design studio a few years ago,” he says, “I showed an image of [musican] David Byrne standing in an empty warehouse with [playwright] Robert Wilson and [artist and actress] Adelle Lutz. There’s a dynamic interaction between the three, with David holding a script, Robert’s hand on his chin in thought, and Adelle gesturing to them. For me, it’s this moment where there’s an idea for a project that’s not yet fully formed that’s often the most important. In the workshop; it’s this ‘what if’ moment where we run through how the central idea is tested, expressed, and developed in the design process.”

In his 20s and 30s, Bull was a marathon runner, adventure racer, and cross-country skier. The discipline and constant practice that went into athletic training, combined with the influence of his somewhat eccentric thesis advisor at MIT, Hungarian architect Imre Halasz, has carried him throughout his professional life.

“Imre’s biggest lesson was this notion of practice,” he says. “You’ve got to do it. To be a really good architect, you’ve got to be tenacious. There are always going to be roadblocks and people who just want to dilute what you’re after — you have to be tenacious in pursuit of what you’re doing.”

Another influence was the work of Carlo Scarpa, a Venetian architect known for his love of craftsmanship and creating Modernist spaces inside historic buildings. For Bull, what resonates is the way Scarpa created a new relationship between the two genres.

“I believe I’m drawn to this idea of interaction and how architecture can build relationships to our environment,” he says. “When I think about works that have influenced me, it’s not so much about a style, but how they’ve built these relationships and created a strong experience of that place.”

He lists a wildly far-ranging number of works seen in his travels, from the Kimbell Art Museum by Louis Kahn and St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, Italy, to Kerry Hill Architects’ Amankora resort in Bhutan, and the amphitheater-like Incan terraces in Moray, Peru. “All of these projects have a certain amount of simplicity and material relationship to history and tradition, a framed view, or an awareness of one’s position in the landscape,” he explains.

At Workshop AD, there’s always a project leader, but at one time or another, everyone in the firm lays a hand on each design. “Throughout the process, people are coming in and out in small-team charrettes to get different voices and perspectives,” Bull says. “I’m usually there in the background, kind of steering; from ‘Have you thought about this? Have you thought about that?’ to directing.”

With many clients, the firm uses what Bull calls postcards. “They’re little 5-by-7s with a question or two on each as a way to get them out of thinking of a house as a series of rooms, and into how they want to live in it and their relationship to the landscape. So we always have these little thoughts like, ‘It was a glorious winter day, it just snowed and we did this, then we went home and …’ We have them write about what they imagine themselves doing in the house as a way for us to get to know them.”

To further guide clients away from thinking of houses as a collection of rooms, at Workshop AD, they talk about territories. “Do you begin your journey when you leave work, at the end of the driveway, or when you’re opening the front door?” he asks. “What are these different territories that you’re moving through, and what are the relationships between them? Because a house is connected to the broader landscape, whether it’s on a hillside in Alaska or on a tight lot in Seattle.”

Much of the firm’s work in Seattle has been creating light-filled, satisfying living spaces on small, subdivided lots further constricted by building codes and just as frequently by budget restrictions. In the end, the designs are like intricate puzzles.

And problem-solving is in the firm’s nature. “I think there’s a certain tidiness and compactness that we strive for,” Bull says, “an idea of efficiency.”

The tidiness carries over into sustainability. “Making things that don’t use a lot of resources to begin with; that’s one piece of it,” he says. “And we think of things very much in terms of systems, which is a description of how we look at a project: energy systems, water systems, daylighting, and just the materials we’re using and where they came from. All these elements come together in a holistic approach.”

A noted project in Alaska is Goldenview, a 5,000-square-foot house in Anchorage. Construction had been halted for more than five years before Workshop AD took over. The firm redesigned the house within the constrictions of the existing steel frame and footprint, and they took on the issues resulting from the long pause. The result is an airy, cleanly modern hillside structure that’s suspended above the terrain like a treehouse and accessed by a bridge.

At Lightbox, in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, a 3,000-square-foot site was subdivided from an existing house on a corner lot. In addition to the limited footprint, there were height and depth restrictions, and a need to be considerate to the occupants of the neighboring structure. By creating a raised section of roof with clerestory windows and adding a “lightbox,” or open pocket garden, the designers were able to flood the living area with light, giving it the experience of a much larger space. The client was a sailor, so Workshop AD approached the project as if fitting the maximum space into a boat.

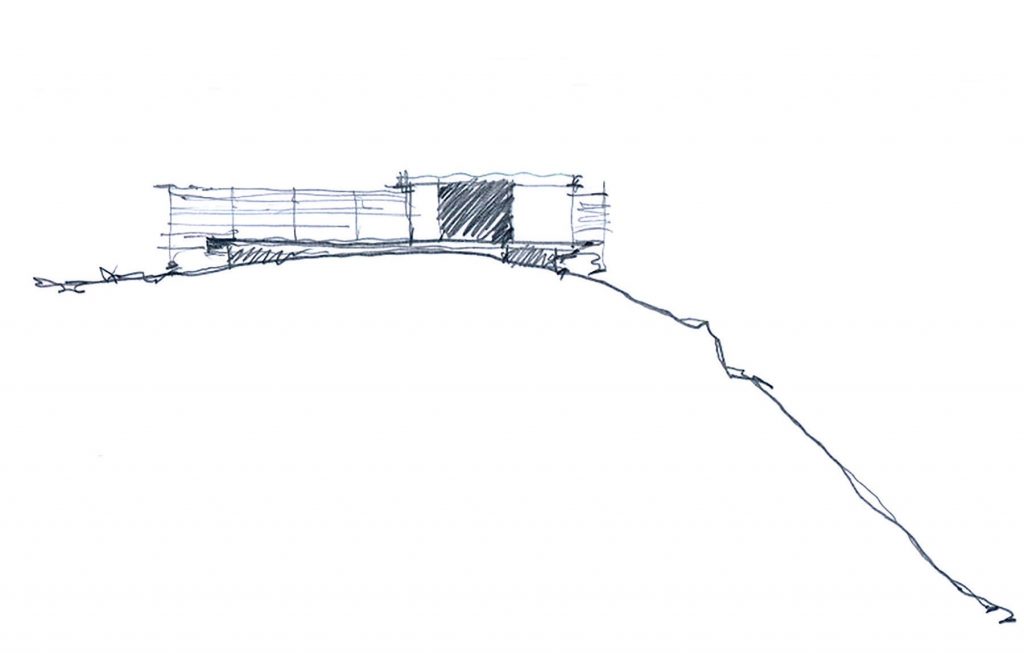

Road D is Bull’s weekend family retreat from Seattle. Just over the Cascade Mountains, spring comes earlier and the sun shines often. Two volumes occupy a ridge above a basalt valley, serving as a meeting place for the two landscapes. The house’s 800 total square feet allow it to be completely off the grid — any larger, and regulations would have required a septic tank, power, and other systems. As it is, the house has a dry toilet and sub-cisterns for collecting water. A breezeway connects the two volumes, one for living and one for sleeping.

As for the future of Workshop AD, Bull says, “I kind of feel like we’re doing really good work at the size we’re at, and we deliberately work with different scales and on different project types to keep things interesting.” It will be interesting to see the direction the firm takes as their body of work continues to grow and their collaborative voice pushes the edges of imagination.

No Comments