06 Sep Rendering: ASPEN EXHILARATION

On the office walls of Aspen, Colorado-based DJArchitects, team photos show the staff mountain biking, hiking through meadows beside pristine lakes, or bombing downhill with powder flying. The exhilaration of outdoor sports in the stunning mid-Rockies setting serves as fuel for their award-winning designs.

In the 1990s, founder David Johnston fled Ohio for Aspen. “The economy took a hit for me,” he explains. “So I came out here to hang out and ski. I didn’t even know architecture was a big thing here, and then I stumbled on a firm that was doing custom homes and had basically blank canvases to work from. There was no need for me to make the drive home.”

In 1997, at the urging of a client, he opened his own firm, and in 2000, he was joined by partner Brian Beazley.

A full view of Hunter Creek, along with its pool and spa, encompasses the surrounding trees of Hunter Creek Valley. Photos: Michael Brands

Beazley had left his New Jersey home because he disliked what was going on there in the building world. At Syracuse University, he’d been steeped in a usual suspects list of modern architecture all-stars.

“However,” he says, “I was really drawn to any designer who melded architecture and the natural environment, and that’s what we do on a day-to-day basis here in the mountains. And that’s why we gravitated to the area, because it’s such an incredible place. I wanted to practice in a place where the surrounding environment and the community are equally as powerful — and respected.”

Johnston emphasizes that a love and respect for the environment is the governing principle behind each project, in the Rockies and elsewhere. They’re equally passionate about living in Aspen and contributing to the community.

The infinity pool is reached via a terrace and the lower level’s expansive outdoor living area.

“People here bring their skis to work and they might go out at lunch every day and ski,” he says. “We love winter, but our summers are so nice that we encourage everyone to take some time off and get out with their families and do things. That’s part of our philosophy.”

“Some skied 100 days this year,” Beazley adds. “That’s not to say we’re slacking off work. We say, bring your dogs to work, because on that afternoon walk down to the river, you may find inspiration. We’re not running a sweatshop here.”

The great room gazes directly at Aspen Mountain, the ski town’s crown jewel.

Including the two partners, the firm numbers only six, and it’s kept intentionally small.

“We’ve stayed a boutique firm by choice,” Beazley says. “There’s so much work here; we could have grown and doubled in size, or become a 12-headed monster. But we really have chosen to stay this size for that family feel, and the communication, where we’re all talking all the time and everybody has a hand in everything.”

One or the other partner will be the primary on a project, but the whole team engages in meetings and design charrettes. Divvying projects so that no one is stuck working on a single variety keeps the design process vital.

The entry’s harmonious combination of stone, glass, and custom steel was created by local fabricator Brandon Walpole of Western Welding. Photos: Michael Brands

“We also match client personalities with architect personalities,” Beazley says. “Then we create a team with a builder, an interior designer, and so on. We want to keep everything in balance, so we don’t necessarily want one person to work on three remodels or two monster homes, or one person has all the affordable housing projects or one person has all the restaurant remodels.”

“We don’t have a style,” Johnston points out. “We’re very client oriented. If someone comes to us and wants more of a contemporary house, we provide services to show them what that means in our eyes, and see if it melds with their eyes. If they want a log house, or if they want a small Victorian remodel with a glass box behind it — over the 25-plus years, no one comes to us for a style. They come to us for a service, personal attention. They know we’re going to research the hell out of any type of theme they bring to the table. We’re going to be sure that we cover all the bases and we knock it out of the park.”

At Thunderbowl Ski Haus, a cascading wood plinth framed in an elegantly curved glass railing connects the main level to the lower family retreat.

Designs begin with sketches. “We love to get a roll of trace out and start sketching,” Beazley says. “But we embrace technology fully here. The rendering programs are very, very powerful and efficient now; [they] really help communicate design and can create the mood, but sometimes we kind of dumb them down to give them a softer feel. We’re constantly trying to find the balance between that hand-drawn world, where we’re trying to keep it loose, with refining things down to very detailed. The main struggle is that in conceptual design we’re telling too much of the story already. It gets a little too rigid, and it’s hard to unwind that. We do 3D models of every project. We model the mechanical systems, we model the structure, we model all the civil engineering, everything. Nothing gets missed. That’s very important to us.”

The ski-in, ski-out house is located on the Thunderbowl ski run at Aspen Highlands. Beautiful year-round, the architecture truly shines during winter’s snowfall.

Aspen was once inconvenient to reach except by private plane, which gave it an air of exclusivity that has always attracted the rich and famous. As a result, it’s full of extravagant houses. The median list price of a single-family house is just under $3 million, but that’s not taking into account the neighborhoods where some of the wealthiest people in the country have built vacation manses. The sheer size of these homes means they consume considerably more energy, or, as The Denver Post put it, they’re “energy hogs.”

Snow-melt systems, heated outdoor pools, spas, terraces, even security systems can add to more conventional energy consumption. The city of Aspen requires offsetting these elements with, for example, photovoltaic systems (as in solar roofs).

DJ Architects engaged local landscape architects Bluegreen to help create a backyard suitable for the entire family and especially magical for children. It includes a custom playground and a wood “Spirit Nest” created by artist Jason Fann.

Earlier in 2023, the Aspen City Council – which is aiming to hit net zero by 2050 – passed some of the most stringent building codes in the state. But for a firm like DJArchitects, sustainability has long been a no-brainer. It’s what you do.

“I don’t think it’s responsible to do anything but that,” Beazley says. “We’ve worked all over the country and it’s never as complex as here. That’s by design, obviously. That’s why this place is so beautiful. We have great respect for all of those codes and we work really well with the building department, planning, and zoning. We work hand in hand with these guys, because this community and the built environment here is so precious. You can’t wind it back, so you’ve got to get it right up front. Yes, they are larger homes, and that’s even more of a reason to make them extremely efficient. So we don’t tell them, ‘Don’t heat your pool, that’s a waste of energy.’ We can tell them, ‘Here’s how you offset that energy.’”

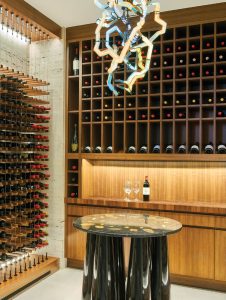

The owners are also avid wine collectors, so they commissioned a wine cellar capable of holding 2,000 bottles, along with a custom, handcrafted tasting table and an abstract light sculpture. Photos: David Patterson

“Our clients who are spending that level of money, they’re educated, they know what’s out there, they know what they need to do,” adds Johnston.

Aspen also presents design challenges unique to mountain architecture.

At Woody Creek Cabin, the architects undertook a full remodel of a dark, 1980s riverside log cabin. To open the structure to the light, they designed for the main living room a steel sliding door system manufactured by Arcadia Custom Luxury Windows and Doors. The area now opens onto a wraparound porch with views of the Roaring Fork River.

The dark original Frasier fir logs in the kitchen and dining area were corn blasted and whitewashed throughout to lighten and brighten the home.

“The retention that’s required for some of these hillside houses is top level, complex,” says Johnston. “Once you’re out of the ground, you’re in a conventional manner, you’re constructing four walls and a roof. And that’s a very understated description, but coming out of the ground is one of the hardest things to get through; and then the other thing we have to deal with, clearly, is water and snow management. Where does the snow go, where does it melt, what’s the runoff like? It goes without saying that a mountain community is pretty unique in that regard.”

A view from the Roaring Fork River includes the outdoor dining area, the fishing porch to the left, and the mother-in-law suite to the right. Photos: Alex Irvin

“Avalanche mitigation,” Beazley adds. “Debris flow. All the civil engineering components behind that. Powder blasts. The 200-year weather events. That’s pretty intense. That’s very real in the environment here. The climate is very intense at the elevation we’re at, so our energy codes are extremely intense in the amount of glazing and energy consumption. And all of that is very tricky to design.”

Interior designer Robyn Scott assisted in creating warm, inviting bedrooms featuring custom artwork from local artists, including the primary bedroom’s featured watercolor mural.

As to the future, Johnston sees the firm moving in a more “board of director-ish” way. “For so long, it was one, then it became two. But now we’re thinking that everybody has a hand in where we’re headed as a firm. We think it’s important for people to have a say in what we do, what projects we take on, or don’t take on; and if we continue like that, as a team, we’re moving forward. I think that’s the best possible way to adapt to the future.”

While the firm has designed houses as far away and as full of different challenges as the Cayman Islands, they’re not anxious to open auxiliary offices. Aspen is their home, their source.

The architects designed a wraparound porch that can comfortably seat the owners’ extended family, enabling them to take in the sights and sounds of life at the confluence of Woody Creek and the Roaring Fork River.

Off the kitchen, an intimate outdoor room of reclaimed barn wood includes such touches of modernity as steel details that offset the cabin’s inherent historic feel. Photos: Alex Irvin

“I really like focusing on the community we live and work in,” Johnston says. “To help create that community fabric and take that experience to these other areas, like Denver, or the islands, and say, ‘This is how you do good architecture, guys.’ We’d like to share our expertise.”

Writer and editor Laurel Delp is a frequent contributor to WA&A and other magazines and websites, including Town & Country, Departures, Sunset, and A Rare World.

No Comments