06 Sep Rendering: Crafting an Experience

“People hire me for my imagination,” explains Craig Wickersham.

The Scottsdale, Arizona-based architect designed his first home when he was only a teenager. His family lived in Santa Cruz, California, and his father was building a new house. The whole operation caught Wickersham’s attention, and he began accumulating the tools — draft tables, T-squares, triangles, and so on. Wickersham’s high school vice principal, who’d studied architecture, mentored the 13-year-old boy and taught him how to design a house. “I just started drawing,” Wickersham says. “You know, floor plans and elevations, and the mechanical plans and the plumbing plans. We worked on every document. And then we went down to the city and got a building permit.”

The exterior is clad in copper and natural stone. Architect Craig Wickersham designed the front door, light fixtures, stained glass, and steel pots at the entry. Photo by: Jim Christy

One of his father’s friends was a developer and offered to build the house, so by age 14, Wickersham’s first architectural design became real. From that point forward, he was the kid who was given Frank Lloyd Wright books for presents, and he spent his time immersed in architecture.

At 17, he managed to get an appointment with Olgivanna Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West. Wright’s widow, who ran Taliesin after his death in 1959, accepted the teenager into the institute before their conversation had ended. “Apparently, it wasn’t very common,” Wickersham says of the on-the-spot acceptance. “Keep in mind, I didn’t have very much education or experience in architecture, so most of the time, I was kept in the studio.”

The complex structure is composed of 105 steel beams. Wickersham also designed the fire features and the pool. He orientated the home to overlook sweeping views of the Arizona desert. Photo by: Jim Christy

Wickersham left Taliesin a few years later in 1985 when Olgivanna died, but by then, he’d developed deep connections to Scottsdale. He got his architecture license and worked for 19 years at Swaback Partners. His brother-in-law, Mark Philp of Allen + Philp Partners, also brought Wickersham on to various projects. All these firms had a profound influence on Scottsdale’s architecture, from resorts and public buildings to houses.

Over the years, Wickersham says his practice has gotten smaller, and his firm now operates with three other employees. “I work as a freelancer for whatever king hires me,” Wickersham says. “My practice is about accumulating high-level performers who work more or less as I do. I have eight or 10 consultants that I’m working with every day, which gives you more freedom than when you have 30 employees. I don’t mean this in a derogatory way, but there’s so much babysitting, so they’re not as highly productive or as light. The bigger they are, the more cumbersome it is, so I’ve watched my colleagues struggle, and I’ve kind of avoided that.”

The materials palette flows from indoors to out. The architect designed all aspects of this home, including the furniture, rugs, and fixtures, and he even selected the art. Photo by: Jim Christy

Wickersham doesn’t just create houses. He designs furniture and lighting and will even scout galleries and buy art for his clients. He plans the pools, landscaping, and hardscaping, and he works with an installer who sources dramatic cacti and boulders. “I’m not just drawing a floor plan and elevations,” he says. “I’m listening to the client and giving them a true custom approach, which is very holistic. I’m designing an entire experience.”

As an architect, he’s been part of the dramatic expansion of Scottsdale. “When I left Taliesin, there was nothing above Shea Boulevard,” he says, referring to a major east-west thoroughfare that’s been developed as construction marches north.

In a project titled Peak View, black steel fascias, metalwork with plank stone, and Hem-Fir ceilings lend a modern appeal. Photo by: Dino Ton

Wickersham gives his clients questionnaires that dig into what they want, adding their imagination to his. But his favorite clients turn him loose. These designs are modern and at one with their environment, particularly when they are located in the Arizona desert.

“In my opinion, the best architects in the U.S. today practice here in Arizona,” he says. “There’s an interesting dynamic between people of extreme wealth and the desert. Some people go to Florida, some people go to Southern California, but there’s a huge population of people here in Arizona who love the environment.”

Inside the home, the contemporary aesthetic is warmed with neutral colored fabrics and earth tones. Photo by: Dino Ton

Wickersham himself is inspired by the sculptural quality of the desert, the cacti, the boulders, and the uninterrupted, sweeping vistas to the mountains. Any design has to start with incorporating these views.

If he has signature materials, they’re earthy and local: copper, stone, stucco. He tries to use an Arizona glass manufacturer, but steel has to be imported.

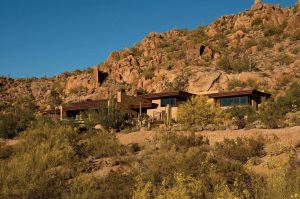

A home titled Alta occupies a high lot. Composed of copper and natural stone, the house is embedded in the boulder-strewn mountainside. Photo by: Jim Christy

Asked about his relationship with sustainability, he replies, “At the AIA, there’s a lot of this sustainability pressure, but in reality, it’s bunk. You build a 30- or 60-story building and call that sustainable? To me, sustainability is using local materials. America started off as fully sustainable, right? You built a log cabin from a tree on the property and from mud from a river. Now because of technological advances, we have materials coming from all over the world. You could go and build a house the way Frank Lloyd Wright did in the desert in the 1930s, where almost everything came from the site — the sand in the concrete; the stones in the walls; everything but the wood.”

The sculpture and art were designed by Wickersham to complement the architecture. Photo by: Jim Christy

He views the seemingly unstoppable spread of building as inevitable. “We have a population that’s exploding. When we’re looking at architecture, it’s the single largest energy use and component in our society — there’s an AIA study that’s readily available. So architecture has to be more and more energy efficient.

The facade is a mixture of textures: copper, natural stone, glass, and smooth stucco. Wickersham even designed the landscaping for Alta. Photo by: Jim Christy

In the meantime, he’s happiest designing every aspect of a house, outside and inside. That’s what custom means to him: something completely original and geared to the client’s unique wants and needs, down to the smallest detail.

In the Peak View House, clean, modern lines intersect with cacti specimens native to the surrounding desert. Photo: Dino Ton

No Comments