09 Jan Rendering: Creativity and Craft

At the far end of a shallow alleyway in Santa Barbara’s El Pueblo Viejo neighborhood, a 19-by-19-foot four-story home wrapped in undulating white plaster has two large keyhole windows, an elliptical garage door, and a front light that dangles from a delicate iron pole stretching the length of the building. It’s somewhat Andalusian, a bit Dr. Seussian, and entirely beautiful.

The structure is known as the Ablitt Tower, after the couple who commissioned it, and architect Jeff Shelton said he initially turned down designing it. He was up on a ladder installing mosaic tile on a home he was just finishing when Neil and Sue Ablitt called to him from the street below, asking if he would also build them a house.

Architect Jeff Shelton drew this sketch of the Ablitt Tower’s dome, with its zig-zag pattern of green and white tile and 6-inch steel ball. Shelton says it’s important to celebrate the place where a building meets the sky.

“No,” he said flat out. “I’m too busy and not taking on any more work.”

But they persisted, arguing the lot was just a block from his office, and then added, apologetically, that it was unfortunately only 20 by 20 feet.

“I’ll take the job!” Shelton said.

Now, 16 years later, the architect says, “Maybe I was getting smart and I knew. But the cool thing about restrictions is, you’re going to get to the point fast.”

The entryway to the Ablitt Tower is wrapped in blue and white tile handcrafted by the Los Angeles company that makes all the ceramic tile in Shelton’s buildings, including the motifs Shelton draws specifically for individual projects.

Shelton, who grew up in Santa Barbara, has designed and built more than 55 homes and buildings there since returning from a stint in Los Angeles 28 years ago. Eight of them are in the city’s historic El Pueblo Viejo, where strict design codes and review boards enforce a unifying theme of early Andalusian-Moorish architecture.

It took three years of planning and review for the Ablitt Tower to receive a permit. After a denial from the city’s planning commission, it won approval from the city council on appeal. Today, it’s affectionately embraced by residents as a delightful addition to the historic district.

Throughout downtown, white-washed and adobe-like exteriors with arches, red-tile roofs, balconies wrapped in wrought iron, and tufts of clinging chartreuse bougainvillea appear everywhere. The rules have allowed the city to carry its Spanish Colonial roots forward and retain an enduring charm, but developers and architects decry the challenges and red tape. (It took three years for the Ablitt Tower to be approved.) Nonetheless, Shelton just keeps interpreting Andalusian-Moorish themes through a lens of mirth.

The large keyhole windows on the tower’s third floor were crafted from black walnut by a local artisan. The 108-foot handrail, also handcrafted in walnut, moves upward in sinuous curves from the first floor to the rooftop deck in a single continuous piece. It turns the corners in a snake-like manner; there’s even a snake’s head at the start and a tail where it ends.

“Our intention is always to give life to the street and to create a building that invites and brings delight to the pedestrian and community,” he says in The Fig District, a new book about the buildings in El Pueblo Viejo he’s designed and built with a loyal band of artisans and craftspeople. And anyone can see delight taking center stage in the details of color and craft. Consider the patterns of alternating tile above windows in a suggestion of eyebrows.

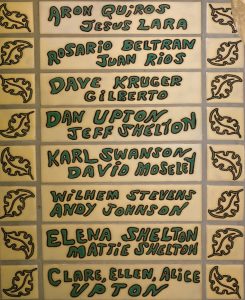

The names of the artisans and craftspeople who worked on Ablitt Tower are painted on a tile that’s adhered to the building, a regular practice on all of Shelton structures.

The eight live-work spaces Shelton and his crew built on East Cota Street are arranged around four courtyards. Gurgling fountains, colorful blooms spilling from Gulliver-sized ceramic pots, and tiled benches say people are the point here. Iron handrails designed by sculptor David Shelton — who happens to be Jeff’s older brother — loop and curl over pickets that tip forward and backward as if walking along. Hand-blown and custom lights held up by wrought-iron fixtures embellish front doors. At night, they shimmer a soft gold color.

Santa Barbara’s parking requirements and a pink flame tree Shelton wanted to preserve determined the shape of the Garden Street Residence. With the living space condensed on the left side of the lot, the structure resembles a giant high-top sneaker — the kind the building’s owner wore every day — earning the name El Zapato.

“I’ll look at every façade as its own sculptural thing,” he says. “I think, so how does that work? And I often go with my gut. Those have to be there; and something has to be there; it needs something; what does it need?”

West of State Street is a mixed-use condominium building known as El Andaluz. Here, seven townhomes overlook a capacious courtyard. The façade features a series of grand Moorish-style arches, opening up to pedestrians what could easily have been a monolith. A tile-wrapped arcade-like entryway flows to a staircase and gate that is — you guessed it — slightly and intentionally droopy, as if exhausted from the strain of its vertical position.

Custom hand-blown glass lights, suspended from wrought iron fixtures, reflect the Andalusian designs that Shelton loves to interpret and inject with a dose of whimsey.

I once asked Shelton why the clock on his El Jardin building has 12 o’clock at 2, and 2 o’clock at 10. He just drew it that way, he says, as if he’d simply been taking dictation from the god of play. Happily, perhaps shockingly, it made it past the review boards.

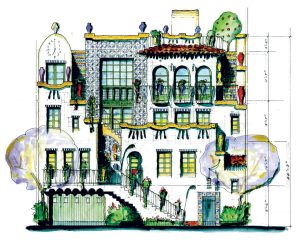

Shelton often looks at his buildings as a whole sculptural piece. This sketch reveals harmonious colors and details.

“There’s no predicting what peculiar idea might appear on a loose sheet of paper,” Shelton says in The Fig District. In our interview, he adds, “I try to respect things that come out and at least give them their chance. They came out for a reason. They may die on the vine; it doesn’t matter. I try to treat those little sketches just like that little voice that maybe talks to you and bugs you about something, or reminds you of something, or helps you with something.”

El Zapato’s unique tile design of interlocking lobsters wraps around the windows and doors. Shelton chose the lobster motif instead of a floral one because the owner is from Maine.

Brian Cearnal, a prominent Santa Barbara architect, puts Shelton’s work on par with Antoni Gaudí of Barcelona, Spain, whose designs are known for their outlandish curves, mosaics, and arched rooflines. “I would hope that Shelton’s influence would be to make the [city] review boards realize that buildings here don’t all have to look like they were designed by dead architects. Let’s allow for innovation from within the spirit and the style.”

El Jardin is a mixed-use building whose design was influenced by Shelton’s trip to Southern Spain. The exterior staircases and an interior courtyard resulted from the constraints of an owner’s feng shui consultant and the city’s design requirements.

Shelton grew up the youngest of four sons on the pastoral grounds of a boys’ prep school that closed in 1933. The family’s home occupied the old infirmary, classrooms, and library. He didn’t live in a conventional house until college.

The whole family is immersed in one artistic endeavor or another. Shelton’s older brother, Ron, is a filmmaker, responsible for “Bull Durham” and “White Men Can’t Jump,” among other films. His father was a jazz musician who played nightly for the family. “He’d hear a Beatles song and turn it into jazz or make something up about what you just said,” Shelton says.

Located on the street named Garden, El Jardin’s garden motif seemed a good fit. The tile design is a black rose, and sculptor David Shelton created the balconies to reflect the shape of a giant succulent leaf. Each balcony makes a silhouette of a flower against the sky when viewed from the sidewalk below.

If you sit down to chat with Shelton about his work, only a minute or two will pass before he starts weaving in the many contributions of his merry band of craftspeople — the plasterers, woodworkers, glass blowers, painters, and others who’ve followed him from one project to another over the decades. “If I don’t talk about them, it’s just a fake little story,” he says. One of them, of course, is his brother David, whose raw ironwork is so integral to his designs, one can hardly imagine a Shelton building without a wavy handrail or sculptural balcony. Their thinking and approach are so similar that when a problem crops up, they often work it out without uttering more than a word or two.

A clock with hours gone haywire was designed after Shelton learned the owner would be running a travel business onsite, sending clients into myriad time zones. A limestone clock-keeper, made by a local artisan, appears to be shaking a finger at the clock’s ineptitude.

Dan Upton has been the contractor on 50 of Shelton’s projects in Santa Barbara. “Nothing Jeff draws is from anything but his head,” Upton says. So when Shelton hands him a sketch with a feature that’s never been done before, for Upton, that’s where the fun starts. “You’re like, ‘Okay, well, where do I get that?’ Well, you don’t. You make it,” Upton says. He searched and searched, for example, for tile makers who could create the original designs Shelton drew for each building — a lobster for El Zapato, a rose for El Jardin, etc. “There is no scroll through and click on this, that, or the other thing. It’s all a blank slate. Jeff draws it, and we figure out how to make it. For us, it’s why we get up in the morning.”

The Cota Street Studios were one of Shelton’s earlier buildings. The outdoor staircases feature raw iron railings created collaboratively by Shelton and his brother David Shelton, an established sculptor. As time has passed, David’s ironwork has accrued prominence and visibility in his brother’s designs.

Every building or home Shelton designs has the names of all the craftspeople involved on a tile that’s embedded somewhere on the structure.

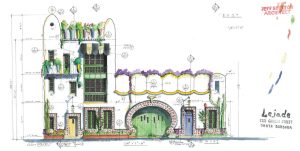

A sketch of El Andaluz shows the mixed-use building’s six elliptical arches ribboned with red and white tile to provide a sense of warmth and playfulness to the façade.

“It’s just been a really important part of my life to work with Jeff and build these buildings,” Upton says. “Being able to leave a legacy in my hometown of beauty, and my three daughters — their footprints and handprints are in the concrete of the driveways and sidewalks and things over different projects. It seemed kind of boring to them at the time, but now they’re really proud of it.”

The interior courtyard of El Andaluz gives residents the full flavor of Andalusian design: painted tiles, iron railings, lush vegetation, and exterior plaster walls that appear to be settling comfortably into the landscape.

Isabelle Walker lives in Santa Barbara, California, where she teaches and writes creative nonfiction and poetry. She has a Master of Fine Arts from Antioch University, Los Angeles.

Based in Santa Barbara, California, photographer Jason Rick specializes in architecture and interiors; jasonrick.com.

No Comments