10 May Rendering: Pragmatic Solutions

You’d think all the sustainability awards that Nathan Good Architects have won would be the primary draw for new clients. But much to the surprise of everyone in the Salem, Oregon-based firm, only about a third of their patrons desire an ambitiously energy-efficient home, says founding principal architect Nathan Good. The rest have been drawn by the firm’s design aesthetic.

But there’s a photo in the January/February 2019 issue of Green Builders magazine that says it all: Good was named the publication’s first Sustainability Superhero. There he is, in a Superman pose, surrounded by the firm’s small staff, all grinning irrepressibly.

In the open-plan great room, a live-edge dining table is by Zapatero from Terra Mai with Cassina leather chairs and barstools. In the living room, vintage Barcelona chairs take advantage of the views. The wood flooring is made of recycled shipping pallets from Southeast Asia. Clerestory windows usher in the morning light. Photo: Indivar Sivanathan

Good knew in the second grade that he was destined to be an architect. However, before incorporating his firm in 2005, he spent five years running an interior design firm in Denver and then additional time consulting and educating architects on sustainable building and design.

Good’s interest in architecture started during childhood, thanks to the distress he felt during heated arguments his parents had over the floor plan for a new house, which led him to ask if he could try. He was so successful at satisfying both parents’ needs that he began thumbing through their magazines, looking for architecture photos. On one search, he discovered an image of John Lautner’s famed 1960 Chemosphere house, an octagonal spaceship-like structure suspended on a pedestal over a 45-degree lot in the Hollywood Hills of Los Angeles. “Here I am,” Good says with a laugh, “a kid in second grade, living on the Kansas prairie, and that Lautner house to me was just the future. So I started getting hooked then, and like so many others, there were Lincoln Logs and Legos and all sorts of cardboard boxes and tree forts, and I was off to the races.”

Glare and heat from the expansive west-facing windows are reduced by overhangs and bands of metal sunscreens, and the windows are triple-pane Unilux from Germany. Photo: Rick Keating

He quickly became a fan of Frank Lloyd Wright as well. Then, in his sophomore year at California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo (where he also received his master’s degree), Good discovered Alvar Aalto, which motivated him to spend his last undergraduate year studying in Denmark. “I traveled all around to see Alvar Aalto’s work in Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and went to see one of the buildings he designed in Iceland. A combination of Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto — that’s my foundation,” Good says.

In addition to Aalto, Good also wanted to study the “sensibility of clean contemporary Danish design,” which the architect still loves today. “Danish Modernism is just elegant design with a use of natural materials,” he says. “And I found that to be an ethos amongst the Danish people as well — frugal but thoughtful. And the aesthetic results of their design was in everything from a table to chairs, to their architecture, their schools, their public spaces, their planning.”

Views range from the Deschutes River to the Cascade Mountains. The dining room light fixture is by Stickbulb; the ceiling is Western red cedar; and the fireplace is Montana moss rock. In the background is a Steinway baby grand piano. Photo: Indivar Sivanathan

A recurring theme is “honesty.” Good designs houses that are elegant but hardly flashy. His structures are pared down to the practical, tailored to individual clients and sites, and universal in their craftsmanship, environmental responsibility, beauty, and longevity.

When asked to explain what he means by “pragmatic solutions” in the firm’s philosophy, he says, “That goes back to the Danish, to things that make sense, that are understandable, not flippant or arbitrary.” He laughs. “I should probably share with you that I spent 10 summers on my uncle’s farm until after I graduated from college, and that’s the epitome of pragmatic. There’s a reason behind everything you do. So I guess you could say that’s in my design DNA; how important it is that things make sense.”

The striking curved plaster wall at Portland Skyline’s east-facing entry extends through the interior and out the western end of the house, uniting the flow of the rooms. Solar panels provide most of the house’s electricity, and the triple-pane windows and doors are from Lowen. Photo: Jeremy Bitterman

Growing up on the prairie, Good had only occasional opportunities — on visits to Kansas City or St. Louis — to see much architecture. But in his search for aesthetic inspiration, he found awe in the grain silos of the Midwest. “They became like cathedrals of the prairie,” he says. “There I developed an interest in the whole aesthetics of pragmatic technology. The way things are designed, there’s a beauty in much of that technology.” He adds that Paris’s Pompidou Center is a great, if not completely successful, effort in that direction. And he was also impressed early on by Ed Mazria, the founder of Architecture 2030, who’s been a leader in the green building movement.

Portland Skyline’s floors are Pacific madrone from Oregon, subtly contrasted by cherry kitchen cabinets and Absolute Black granite countertops. The heavy wood beams were salvaged from the house previously on the site. Photo: Jeremy Bitterman

After moving to Oregon, Good worked with Portland General Electric to form a business that encouraged people to reduce energy usage. “Then we started providing consulting services to architects and building owners on how to reduce their environmental footprint, and that was a very successful program,” he says. “It received a lot of national attention, and it launched me as a green building expert.”

Eventually, he tired of the travel consulting entailed. He was tired, as well, of primarily consulting rather than designing. “Most of my work,” he explains, “was in the commercial building arena, and what I really missed was the intimacy of working with residential clients. So I shifted my focus to single-family custom homes.”

The stairs are Forest Stewardship Council-certified Pacific madrone wood, with windows providing natural daylighting. Upstairs are three bedrooms, and downstairs the family room and exercise room. Photo: Darius Kuda

Good is still engaged in education, but now it’s part of the process of working with clients and construction firms. He avoids questionnaires that unearth a client’s needs and aspirations. Instead, he spends time with them, walking the sites, observing the wind and the sun’s passage, and helping them express their desires. The shape of the award-winning Cannon Beach House, for example, was inspired by a client’s love of “the curvature of sand dunes.”

“We do it in real time,” Good says.

The dining room at the Cannon Beach House features a live-edge table of wind-toppled Douglas fir. The same wood forms the heavy timber frames in the Camas Basalt thermal storage wall.

Utilizing natural light is another critical element of the firm’s designs, especially in the often overcast Pacific Northwest. “A properly day-lit home bathes the interiors with soft, indirect light,” says Good. In certain seasons or areas, light can provide passive heat, but for Good, its primary importance is enhancing the inhabitants’ mood and health, or, as he puts it: “the joy of experiencing how the quality of light shifts throughout the day and over the seasons, how it enhances the color and texture of an interior environment, and how it connects us to a time and place.”

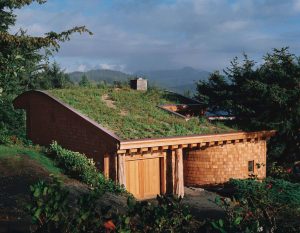

The green roof softens the view of Cannon Beach for the houses above it and reduces the rate of rainwater flowing into the neighborhood stormwater system. The home was designed around an ancient Sitka spruce, and the Western red cedar shakes were sourced from an Audubon forest in Washington. Photos: Nathan Good

Good tries to include numerous energy-saving elements in his projects. “Indoor air quality is one of the features that we don’t compromise on and for which we advocate the most stringently,” he says. “But if they don’t want to go with super-insulated walls or they want double-pane rather than triple-pane windows, we’ll back off … ” Other elements might include a rainwater collection system, a Tesla power wall, and a backup generator.

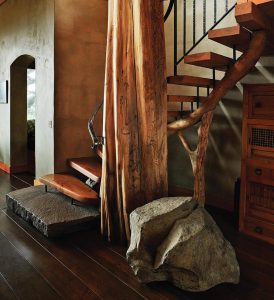

An incense cedar column anchors the staircase, which leads to a loft. The stair treads are wind-fallen Douglas fir, and the boulder was originally meant for a fireplace but was too heavy to move after it was rejected. Photo: Daniel Root

Fire mitigation is also always considered. Even on the coast, Good uses metal roofing and noncombustible exteriors. There are no crawl spaces or open vents where sparks might enter. Some clients have installed outdoor sprinkler systems that come on only when a fire is detected. “It brings up something that’s really hard for me to share,” he says. “In my own heart and mind, we’ve gone through trying to change the market to prepare people for the inevitability of climate change.” But the built environment remains both vulnerable and responsible for a large degree of carbon in the atmosphere. He feels now they’re building homes defensively as much as for energy efficiency.

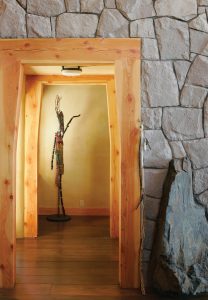

A wooden sculpture anchors the hallway.

Over the last decade, the firm has built eight LEED-certified houses (including Platinum, the highest rating), two passive houses, and 14 Earth Advantage-certified houses. Still more are coming. But as Good points out, getting a LEED rating isn’t for everyone. It’s complicated, and not everyone who’s built an energy-efficient house cares about ratings.

Two incense cedars serve as natural columns to support the south-facing covered porch. The bamboo privacy screen was designed by Shannon Belthor. An evacuated tube solar-thermal system provides heating and hot water to the house. Photos: Greg Kozawa

These days the firm is a five-person team, which includes Good’s son, Forrest, an architect and a partner at the firm; architect Lydia Jesse Peters, who was Good’s first hire 18 years ago; interior designer Emily Doerfler; and Meghan Laro, another original hire and the office manager. They’re a family, and often go on outings together. These days, Good is slowly inching back so that Forrest and Lydia can take charge of more projects. In four years, he plans to step down and leave the practice to his son.

No Comments