08 Nov Western Landmark: The Mission Inn

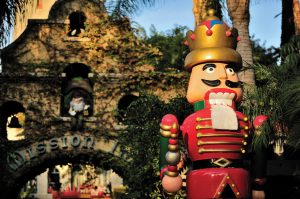

In one of America’s most spectacular holiday displays, the Mission Inn presents its annual Festival of Lights for six weeks starting the day after Thanksgiving. More than four million electric bulbs decorate the square-block property in an extravaganza that includes upwards of 400 animated figures, giant nutcrackers, a gingerbread house, and even artificial falling snow. Hundreds of thousands of people flock to the hotel in Southern California’s “Inland Empire” of Riverside, about an hour east of Los Angeles.

The travertine-tiled courtyard of the St. Francis Chapel includes, to the left of its entrance, a Famous Fliers’ Wall that pays tribute to great American aviators.

“It’s like an absolutely free Disneyland,” says Kelly Roberts, the hotel’s vice chairman and chief operating officer since 1992, when she and her husband, Duane, purchased the property. Kelly credits Duane, a Riverside native, with the original inspiration to launch the festival in 1993. “He remembers getting in his family’s car and driving to see all the beautiful homes lit up at Christmastime. Duane wanted to provide that kind of experience as a gift for everyone in our community,” she says.

The design of the Mission Inn’s secluded Alhambra Court was inspired by a Moorish palace in Granada, Spain.

Such sentiments suit the Mission Inn, which boasts a family history almost as long as Riverside’s. Four years after the town’s founding in 1870, a civil engineer named Christopher Columbus Miller was commissioned to expand the irrigation canal system. He moved his family to Riverside from Wisconsin. The following year, in lieu of payment for his services, he received a square block of land downtown, where he built a two-story, 12-room hotel that he called Glenwood Cottage. Five years later, his older son, Frank, bought the property for $5,000, and expanded it to 75 rooms by 1886.

A giant nutcracker greets holiday guests at the hotel’s main entrance.

Frank Miller had good reason to grow the hotel. From two Brazilian orange seedlings shipped to the city from Washington, D.C., in 1873, Riverside’s citrus industry boomed. Twelve years later, it was hailed as the “greatest orange growing city in the world,” with lucrative groves that gave it the nation’s highest per capita income by 1895.

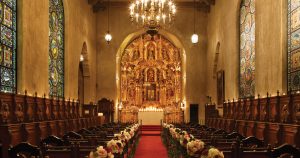

Riverside began attracting wealthy Easterners escaping winter, and Miller’s Glenwood Hotel was the place to stay. In 1902, architect Arthur B. Benton designed an addition with more than 200 guest rooms, in a Mission Revival style that evoked California’s Spanish Colonial past. Miller continued expanding his rechristened Glenwood Mission Inn, adding a 45-room Cloister Wing in 1911; a Spanish Wing by famed architect Myron Hunt, including 10 guestrooms and an art gallery filled with European paintings, completed in 1915; and, between 1929 and 1931, an International Rotunda and the St. Francis Chapel, featuring seven of the hotel’s eight Tiffany stained-glass windows.

Inside the St. Francis Chapel, Tiffany stained-glass windows flank an 18th-century Mexican altar, carved from cedar and covered in gold leaf. It was shipped to the hotel without assembly instructions in 32 pieces designed to be held together with pegs, making it “the world’s first 3-D jigsaw puzzle,” quips Ursula Dubé, a docent at the Mission Inn.

Along the way, the Mission Inn also became a showcase for Miller’s ever-growing collection of treasures. Highlights from its vast holdings include a complete set of Henry Chapman Ford’s 19th-century oil paintings of California’s historic Spanish missions; The California Alps, a massive oil of the Sierra Nevada painted in 1874 by William Keith; The Charge Up San Juan Hill, Vasily Vereshchagin’s 1900 canvas depicting Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War; and a vast bell collection, of which some 400 remain, the most famous dating from 1247 A.D. “A friend of mine constantly says that the artifacts here may be worth as much as the hotel itself,” says Skip Forster, one of some 100 docents who leads public tours of the hotel with the Mission Inn Foundation.

Portraits of U.S. Presidents who’ve visited the hotel welcome guests to the Presidential Lounge. Photos courtesy of the Mission Inn

Not surprisingly, the Mission Inn welcomed elite guests from every walk of life, including industrialist Andrew Carnegie, naturalist John Muir, disability rights activist Helen Keller, aviator Amelia Earhart, and educator and civil rights leader Booker T. Washington. Movie stars from Hollywood’s Golden Age also flocked there, among them Bette Davis, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Spencer Tracy, and Elizabeth Taylor. Ten U.S. presidents have also visited, and their portraits now appear outside the Presidential Lounge.

Beneath the Amistad Dome, the Bridal Suite’s curved, painted ceiling adds an air of romance.

Despite its allure and fame, the Mission Inn began declining in the mid-1950s after Frank Miller’s grandchildren sold it. For a time, despite achieving National Historic Landmark status in 1977, it seemed destined for demolition — until Duane and Kelly bought it, restored it to its former glory, and updated it with modern amenities, including the luxurious, Tuscan-style Kelly’s Spa.

Duane’s restaurant showcases the painting The Charge Up San Juan Hill, featuring Rough Rider Teddy Roosevelt (center), who stayed at the Mission Inn in 1903. Winner of a Wine Spectator award of excellence, the wine list at the hotel features Oregon’s Irvine and Roberts Family Vineyards, a partnership that includes the hotel’s owners.

Yet, some upscale travelers may still ask one bothersome question: Why visit Riverside? Fortunately, persuasive answers abound. The town provides a convenient halfway point between Los Angeles and Palm Springs for leisurely road trips. It also offers idyllic tree-lined neighborhoods filled with residential architectural gems; the 1,900-acre University of California Riverside campus; the nearby Riverside Art Museum in a 1929 Classical Mediterranean building by Hearst Castle architect Julia Morgan; and, adjacent to the hotel, the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture, the home to the comedian’s extensive personal collection, opening in May.

Launched in 2004, Kelly’s Spa has the ambiance of an ancient Tuscan villa.

Then again, myriad reasons exist never to leave the hotel’s confines. “It’s like going to Europe without leaving the United States,” says Antoine Maalouf, the hotel’s vice president and general manager. Besides lingering in rooms appointed with antiques, dining in the four restaurants, luxuriating in the spa, or relaxing by the palm-fringed swimming pool, guests could spend many hours simply wandering the labyrinthine corridors and walkways, delighting in seemingly endless decorative details and priceless treasures. As Kelly Roberts says, “The Mission Inn is the gem of the Inland Empire.”

Along the pathway to the lobby, the late-19th-century iron-alloy Nanjing Bell, weighing 3,500 pounds, was given as a birthday present in 1914 to the Mission Inn’s founder Frank Miller by his daughter Allis.

The spacious, antique-filled Alhambra Suite has welcomed distinguished visitors, including Richard and Pat Nixon, Ronald and Nancy Reagan, and Robert F. Kennedy.

With its spiral staircase, pillars, arches, and wrought-iron railings, the 1929-1931 International Rotunda was inspired by founder Frank Miller’s dedication to world peace.

No Comments