01 Feb A Class of his Own

UNDER THE WATCHFUL EYE and unerring hand of artist Logan Maxwell Hagege, the deserts of the American Southwest come marching to life in a parade of angular images that capture the spare beauty of an arid landscape and of an ancient and enduring Native American culture shaped by the extremes of its environment.

There can be no missteps in the unyielding desert, a stern taskmaster that tenders no forgiveness for the unschooled sojourner who neglects to carry such necessities as water and who strays too far from shelter in the unrelenting sun.

It is as much a place of imagination as harsh reality, a land where massive mesas can be dwarfed by towering clouds and where dreams can be as broad as the horizon. For Hagege, vast deserts are the source of his inspiration — but not the limit of his imagination.

The 33-year-old California artist has emblazoned his website with the legend, “Protesting against the rising tide of conformity,” but his paintings will persuade you if the words do not.

Hagege has marshaled all the artistic forces that stem from his years of formal study to create works informed by Modernism in design and color but not mastered by it, and to achieve a style that is produced by a vision so individual that it comes as a fresh surprise to learn of its universal appeal.

Art experts and collectors of Hagege’s works are not so much admiring of his paintings of the peoples and land-scapes of the American Southwest as they are mesmerized by them.

“Logan has an entirely unique style. You can’t call it Realism; you can’t call it Abstract. He is sometimes categorized as a Western artist and sometimes categorized as a contemporary artist. In truth, he’s in a class of his own,” says Beau Alexander, who, as owner of Maxwell Alexander Gallery near Los Angeles, represents Hagege.

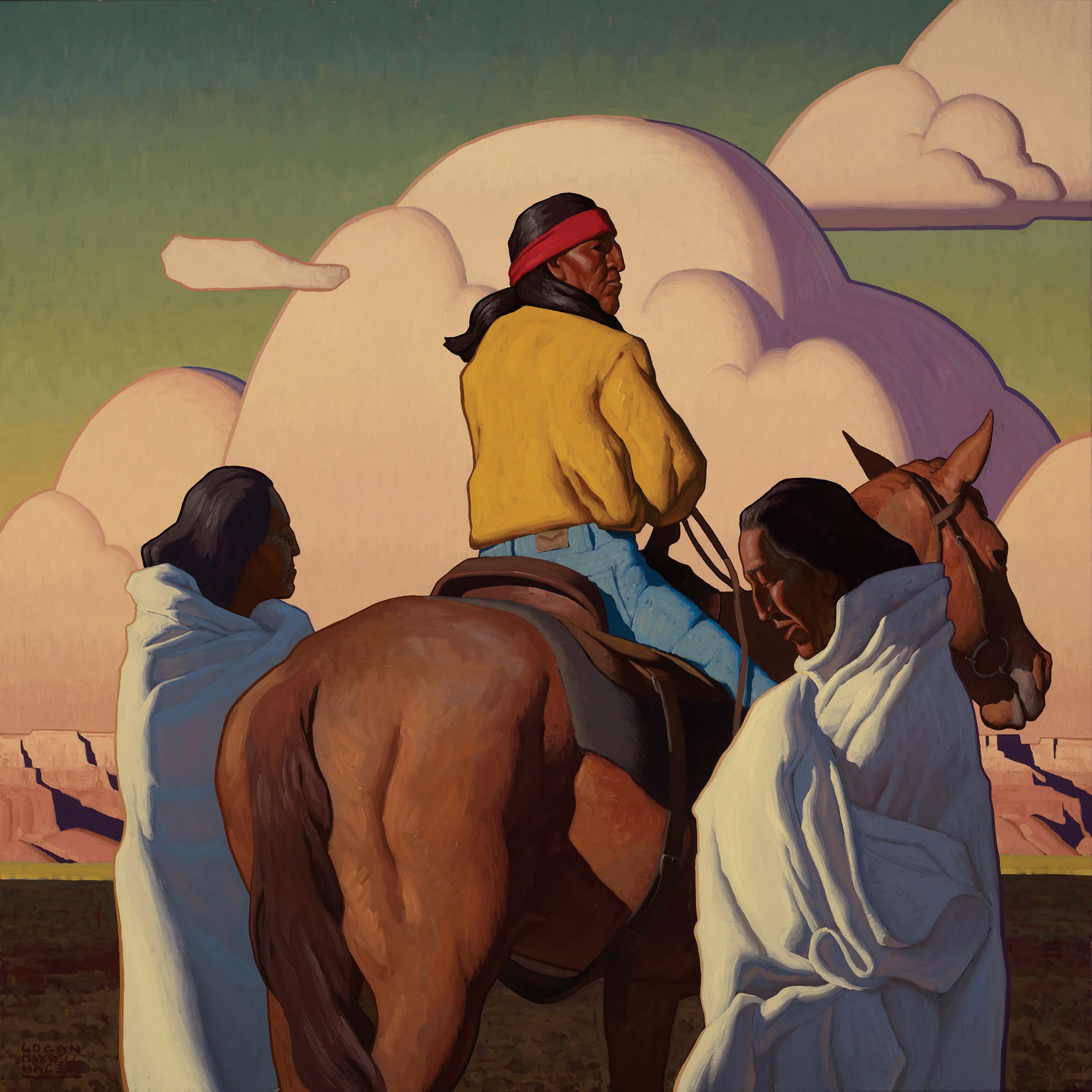

Echoing the subjects of the early 20th-century Taos Society of Artists in New Mexico, Hagege’s desert figures are mostly Native Americans, sometimes wrapped in blankets, often depicted in profile where facial planes mimic the hard-edged beauty of flat lands uplifted by rock features but overtly ornamented by sky.

Hagege is an explorer uncovering worlds inhabited by wanderers like himself. A face and figure from the San Felipe Pueblo outside Albuquerque, New Mexico, appears and reappears, his craggy features softened against the backdrop of outsize, geometric clouds in Full Sky, an oil-on-linen composition, and in the oil The Sun and the Clouds.

“A lot of the people I paint are constantly wandering, they are walking in a certain direction, they appear to be going somewhere, but it’s unclear where,” says Hagege.

They are the artist in other guises: nonconformists, searchers whose objects are indefinable, seekers of such things as are found in the desert, where openness acts as a kind of cover.

It is a land of statements about resilience, of desert creatures such as lizards and of human community, which can fend so well with so little. What is hidden is revealed by Hagege, a maestro who uses contrast to sharpen color and mood to subdue it.

That technique reaches a crescendo in Monument Valley Summer, a landscape in which vertical rock formations worn by wind and abrasion form a symphony of rust reds and coral pinks intensified by an overarching white cloud and muddy gray sky.

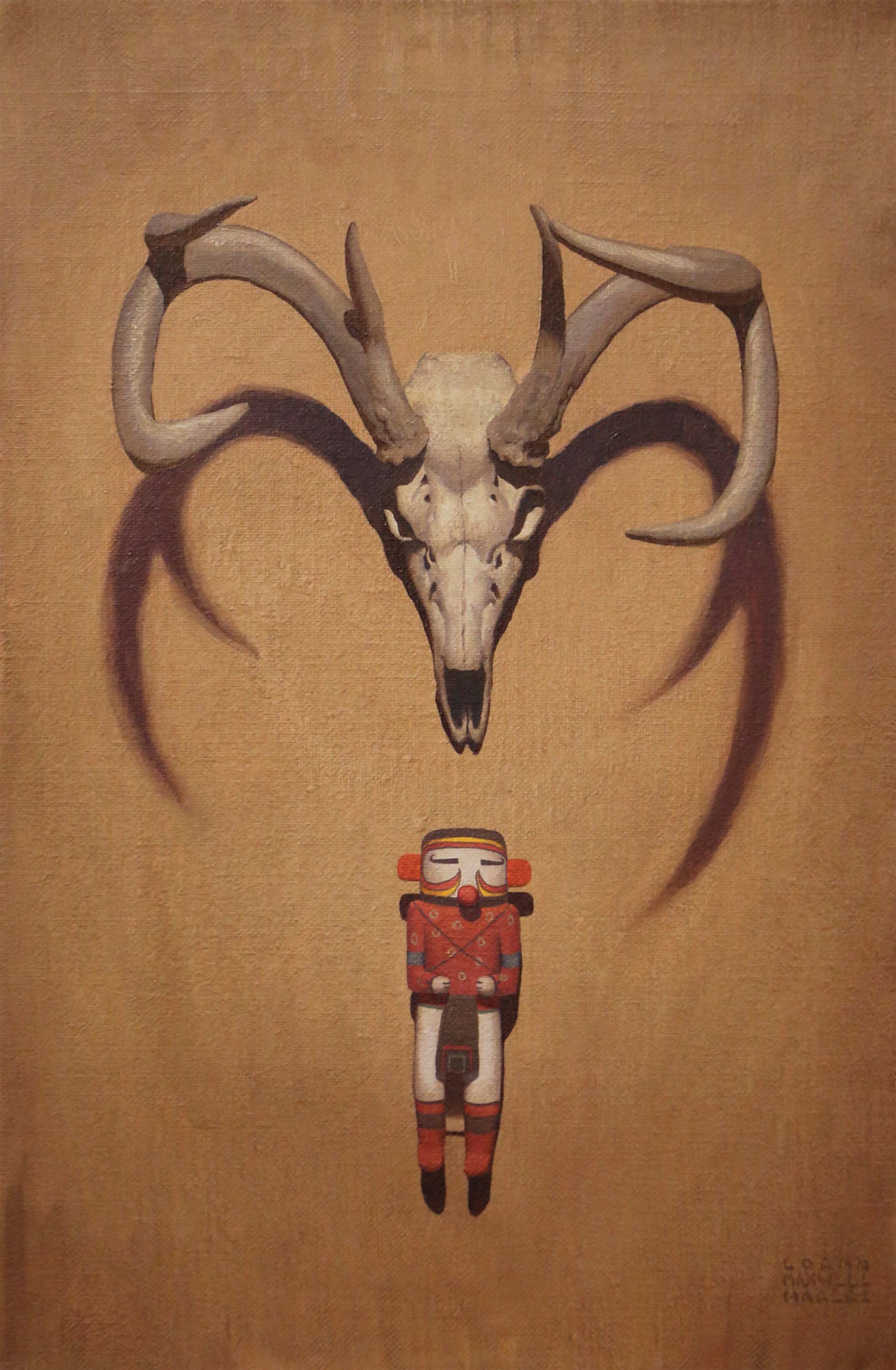

There is little that is static in a Hagege work, with movement the natural rhythm of a restless brilliance that finds its voice in Floating Skull at Vermillion Cliffs, a painting that evokes works with animal skulls by Modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe.

Peter Riess, director of Western art at Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, says Hagege’s work references O’Keeffe and Taos artists such as Gerard Curtis Delano, but Hagege has his own vernacular, causing his shows at the gallery to all but sell out.

Like Taos artists who found a nation within a nation in northern New Mexico, Hagege depicts a region that is in America but not of its main-stream culture.

Referring to the early local art colony and its members, Jina Brenneman, curator of the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, says, “In many respects and, for their time, they were outlaws.”

For Hagege, rules bend at the insistence of imagination rather than will. Realism is juxtaposed with Abstraction because classical training paired with creativity permits it to be so.

“There’s a role for bucking the trend,” he says.

Western Gothic takes that role center stage. A deer skull crowned by a rack of antlers looms, outsize, over a tiny Hopi Katsina doll in a painting whose power is not muted by the sparseness of the design. Before the image appeared on canvas, it took form in Hagege’s mind and it spoke to what he describes as a process of distilling the complex within the simple.

“It’s not easy to bring things down to their fewest elements and still make a painting work,” he says.

Hagege strikes no inauthentic notes in his paintings. A lesser artist might succumb to temptation and splash color on the unadorned white blankets that cloak two of the three American Indians in The Rising Clouds, a triangular composition whose edges are blunted by a background of rounded clouds. The painting is yet another indication that Hagege has mastered that fine point of fine art: knowing what to leave out.

It is a talent shown in relief by such established 20th-century American artists as Maynard Dixon, whose later Modernism still was paired — to advantage — with Western themes.

It is a heady time for Hagege, whose work will be show-cased in February and March along with the works of other acclaimed artists at the Masters of the American West, the signature annual event at the Autry National Center in Los Angeles.

It was at a past Masters that Maryvonne Leshe, managing partner of Trailside Galleries in Jackson, Wyoming, and a class of Scottsdale, Arizona, was entranced by a Hagege painting and sought to purchase it. The piece was acquired by another buyer, but Leshe won the prize: to represent the artist at her galleries. Hagege is to be at the center of a show at the Wyoming gallery in September, at the height of the Jackson Hole Fall Arts Festival.

“What attracts me to his work, his strong palette and modern designs, is that it is different from the work of other artists; it’s refreshing,” she says.

Hagege is unwilling to rest on laurels he has gained as an artist who is still relatively young. Like the landscapes he prefers, he has no wish to be boxed in.

“I’m going to keep changing as I go on, one painting leads to the next and that one to another,” he says.

- “The Rising Clouds” | Oil | 60 x 60 inches

- “The Sun and The Clouds” | Oil | 40 x 40 inches

- “Above the Mountains” | Oil | 40 x 60 inches

- “Western Gothic” | Oil | 30 x 20 inches

- “The Rain Falls” | Oil | 80 x 52 inches

No Comments