06 May A Love of the Western Way

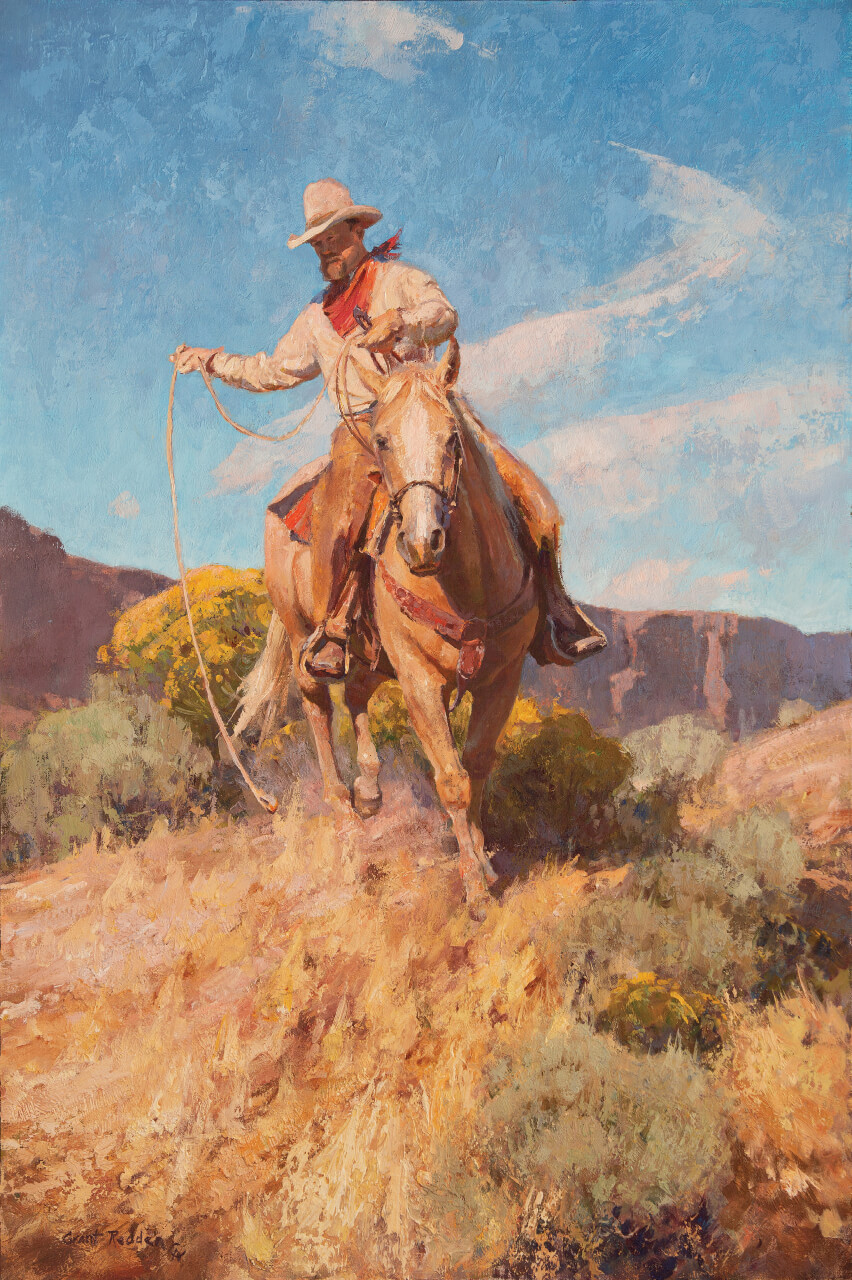

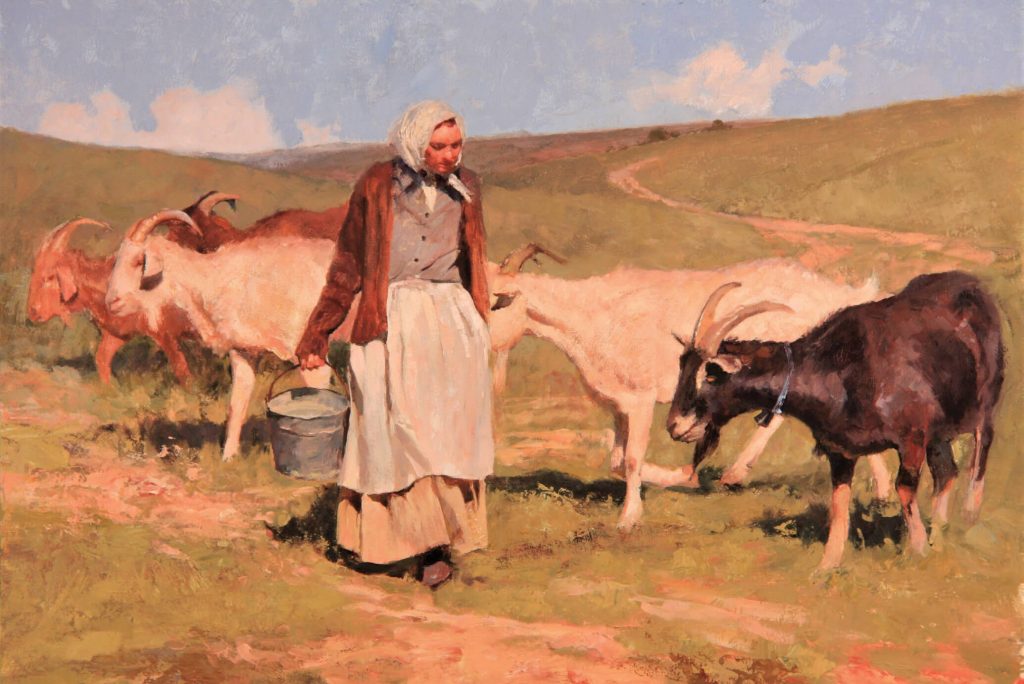

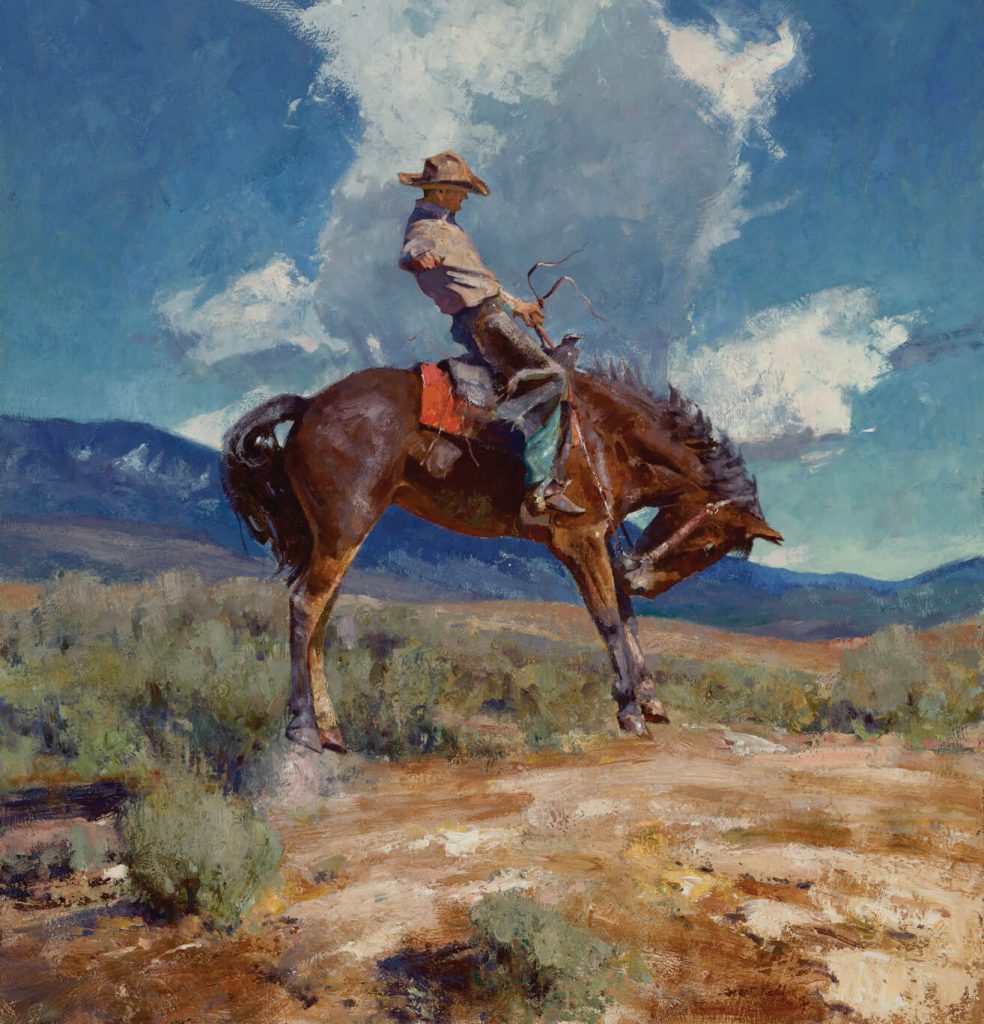

Grant Redden’s paintings of the people, animals, and terrain of the West have a gentle, almost tender luminosity. Even in portraying the rugged trappings of ranch life and the features of an often unforgiving landscape, his works have an intimate, deeply attentive quality that strikes a chord in art lovers across the nation — including those who have never set foot on the Wyoming landscape where Redden, a self-taught artist, has spent his whole life.

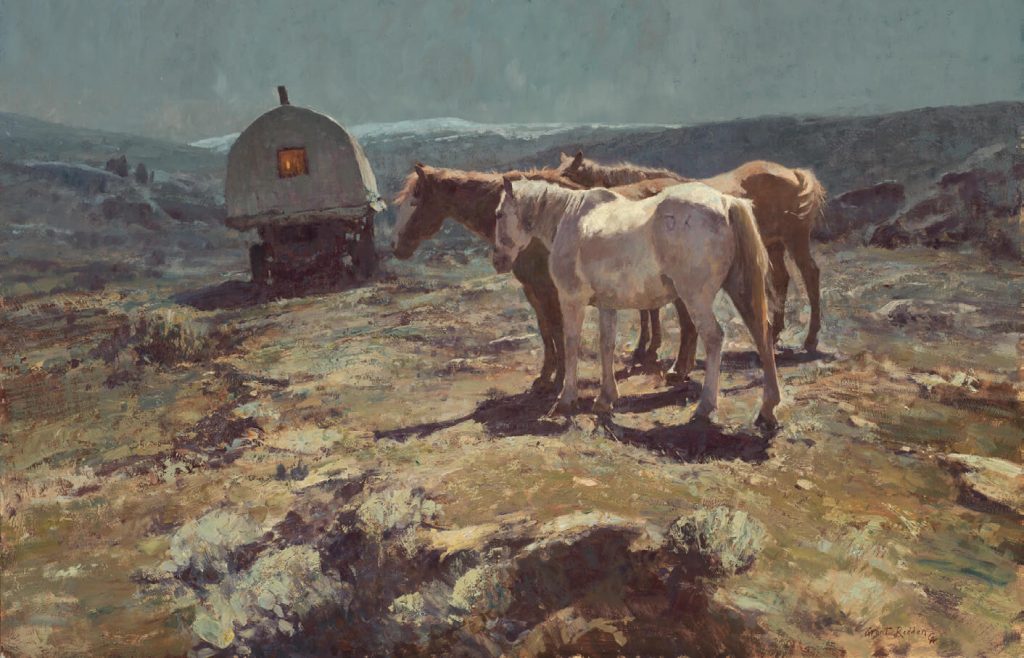

Decidedly painterly, his art is distinguished in part by a palette that feels at once true to life and transcendent: the moody and fleeting deep blue of a sky on the threshold between dusk and darkness; the almost-opalescent tints of pink, aqua, and gold reflected by a pioneer girl’s white apron; the lamplit orange glow that radiates from the window of a lone sheepherder’s wagon — Redden’s rendering of light and color speaks to universal human emotions.

“I’m always surprised, and a little confused, about people’s reaction to my colors and my edges,” he confesses with characteristic modesty. “I just don’t understand their reaction to them. This is the way I paint. I can’t do anything about it,” he adds — a fact that comes as a relief to fans of his work. For any type of artist, a certain degree of obliviousness to one’s own unique voice is a blessing; it ensures they can retain their singular style without self-consciousness or, worse yet, self-caricature. This has been the case with Redden, whose consistently evocative work has earned him the honor of inclusion among the Cowboy Artists of America. Rather than resting on his laurels, however, Redden remains humbly driven to continually grow and improve.

Now 60, he still has the obsessive passion of a younger, fledgling artist. “My main reason for getting up and going into the studio every day,” he says, “is to become a better painter, to become more capable, and create more beautiful textures. I spend a lot of time studying the Old Masters. I love to go to museums and get my nose up close. I just want to practice and get better and better every day.”

Redden’s earnest commitment to his artistic growth was evident many years ago. As a young husband and father of eight who supported his family by conducting real estate appraisals, he found that his lifelong love of painting would periodically break through the routines and responsibilities of everyday life and demand his attention. “I would go on these art binges where I would draw and paint, mostly watercolor, as much as I could. Then I’d go two or three months without doing it. Then I’d do it some more,” he says.

Eventually, Redden sought out a mentor who might help him turn his passion into a real living: Jim Norton, a successful cowboy artist, had settled in his hometown. “I called him up and said, ‘Hey, I want to be an artist,’ Redden recalls. “He agreed to look at some of my work. He looked at it for a while and didn’t say anything, and then he finally said, ‘Well, it’s better than I thought it would be.’ And then he took me down to his studio and introduced me to artists like [Joaquin] Sorolla and [John Singer] Sargent, and showed me what he did to make a living, and told me what I should do to become a painter.”

Encouraged, Redden studied the work of the aforementioned masters, along with that of Anders Zorn, Heinrich von Zugel, and others, and he took workshops. “I just kept painting and painting, and every month or so, I’d take my work down to [Norton], and he would critique it and coach me.”

With Norton’s encouragement, Redden shifted from watercolors to oils. “One of the things I love about oil paint is the type of craftsmanship you can put into it, the layering of color, the buildup of paint to get beautiful texture,” says Redden. “A painting should be compelling from across the room, and that is primarily dependent on its design: the arrangement of dark and light shapes. And [looking at it from a distance of] 3 feet should also be really interesting. And then 3 inches away from the painting should be really interesting as well, and that’s when you start to look at the surface: the different levels of paint and color and the handling of the pigment. That’s why I love oil painting.”

While his medium changed from watercolor, his favorite subject matter remained the same. “The landscape is my first love,” he says. Redden is most compelled by the land, as well as the animals and people who live in close relationship with it. Perhaps this relationship is part of what viewers respond to upon seeing Redden’s paintings — a sense of connection many of us remember, miss, or long for.

Growing up on a Wyoming sheep ranch, Redden was part of a web of interdependence that still holds meaning for him. When the boy wasn’t blasting through annual boxes of crayons and filling art tablets, he was working outdoors with his family. “I love animals,” he says, “and they’re critical to the Western lifestyle, especially in the old days when every job that you had to do on a farm or a ranch you did with animals. Nowadays, everybody just hops on their four-wheeler, pickup truck, or tractor to do the work. In the old days, you were more connected to things. It’s a cool feeling to listen to the jingle of a harness, the smell of the animals, the sweat, the thump of their feet on the earth. I think there’s a lot of beauty that’s been lost in [the contemporary ranching] lifestyle, where we start up the motor, turn on the air conditioner and the music. You know, we’re missing so much that can connect us to the land.”

It’s these types of experiences that Redden’s paintings bring to life. In celebrating that sense of connection, Redden eschews photorealism in favor of soft edges that link his paintings to those of the Old Masters who inspire him. “He’s working in the tradition of a lot of great painters,” says Seth Hopkins, executive director of the Booth Western Art Museum, who considers Redden “one of the most technically proficient artists making Western art today” and especially appreciates his renderings of “sheepherding families, and the family scenes, things that not everybody’s painting. It’s not just cowboys or Indians…”

Work, men, women, children, cows, sheep, horses, seasons, night, and day — none of these primal facets of life seem separate from the others when rendered by Redden’s brushstrokes — nor do they seem far away, though many of his works are set at the turn of the century. “A lot of the things that I paint, I’ve experienced myself. When I paint a nocturne of a cowboy sitting on the ground in front of his horse, in the dark, in the sagebrush, I’ve experienced that. There’s a quiet out there that I think affects our personalities and our view of the world,” he says. “I paint what I know.”

No Comments