01 Sep A Sculptor's Sculptor

THE MOUNTAINOUS, RIVER-CARVED LANDSCAPE OF HIS NATIVE NAIROVI, KENYA, bears little likeness to the low-lying flatlands of North Texas but the distance between the disparate geography and contrast in cultures is a matter of degree for internationally acclaimed artist Robert Glen.

If Glen can claim a legacy in sculpture that stretches beyond the expanses of East Africa and its exotic wildlife, then it is showcased in a granite-encased plaza in the upscale planned community of Las Colinas in Irving, Texas. That is where Glen’s band of nine larger-than-life bronze mustangs gallop through a 400-foot stylized arroyo amid a sleek office complex that contains some of America’s leading corporations.

The Mustangs of Las Colinas, which brand the complex known as Williams Square and which rival the Alamo as one of the most visited sites in Texas, this year celebrates its 25th anniversary. More than seven years in the making and casting, the sculpture-cum-landmark is — literally — a textbook example of the nexus between art and architecture and the largely unheralded achievement, in an era of cost-conscious development, of art dictating design.

Matched in magnificence with the mythical mares of Diomedes, but devoid of their savagery, the horses shaped by Glen are monumental. The effect of the bronze animals is powerful, not only because of their size; instead, the mustangs command attention because they embody what their creator conceived as the wild and free spirit of Texas and, more broadly, the American Southwest.

It is a testament to the puissance of the sculpture that it has imbued Las Colinas with a cachet, and this despite the development’s position as part of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex.

It is by intention that the mustangs symbolize a near past in which horses whose bloodlines linked to herds imported by Spanish conquistadors thundered across the wide-open spaces of the West.

Ben Carpenter, the business magnate behind Las Colinas, sought to preserve for generations an abstraction of the West Texas prairie framed by the high-end urban development that once made up the grasslands of his family ranch.

Encapsulating his philosophy in a memo to his staff in 1974, Carpenter wrote, “We are merely the custodians of this property during its important stage of development. None of us can take it with us into immortality, so let’s resist the attitude of some real estate developers in the past to squeeze out the very last short-term dollar.”

Perhaps chance was not at issue in the decades-distant meeting between Glen and Carpenter, a hunting enthusiast with a penchant for seeking big game on safari in remote reaches of Africa. He was introduced to Glen by a mutual friend and, in the fashion of later patrons like Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II and the Aga Kahn, Carpenter began to collect the sculptor’s tabletop wildlife bronzes.

Poised to transform ranchlands into the exclusive enclave that is Las Colinas, Carpenter envisioned a plaza that would function much like the public forum in the urban architecture of ancient Rome. He turned to Glen in hopes of a monument that would evoke the image of his beloved Texas, a quality of independence whose limit fades against the vast backdrop of the Lone Star State.

Today, at 69, Glen can tally his share of monuments, including a statue of Carpenter in Irving and a figurative bronze in San Jose, California. And he can boast exhibits of his signature wildlife work from London to Monaco. But when Carpenter inquired about Glen’s interest in “doing some horses for a project,” as Glen recalls, the artist was unaware of the sheer magnitude of the proposal.

It would take nearly eight years of study, design and unadorned hard labor for Glen to produce the piece that Carpenter approved nearly unaltered. Once Glen unveiled the scale models of the sculpture, Carpenter presented them to the late Jim Reeves, a principal of SWA Group in San Francisco.

“Ben told him this would be the artwork and everything should be designed around it,” says Mary Higbie, who mans the museum devoted to the sculpture, aptly named the Mustang Museum. “Mr. Carpenter knew exactly what he wanted.”

Glen sought to capture what he refers to as the essence of the creatures. His early training in the Denver studio of the legendary taxidermist Coloman Jonas gave Glen an intimate understanding of the anatomy of an animal but art has ever demanded something more.

“When you are looking at an animal, you are not just looking at the structure,” says Glen, who for more than 15 years has lived among the animals of Africa in a primitive camp studio — sans electricity and running water — in Tanzania’s Ruaha National Park. “You are looking at how the animal is, how it moves, almost what it feels. To assess an animal you must get closer to what it actually is rather than concentrating on appearance and dealing in generalities.

“I’ve seen literally thousands of elephants. But even today, with as much as I think I know, I must go out and sit with elephants. You must learn to see beneath the bone, understanding as much as you can about what they are. Then you take a wee bit of that and go back and put it together with what you think you know.”

It is a tradition steeped in time, with early adherents of Western art — Remington, Rungius — living for stretches with the animals and in the environment that comprised their oeuvres.

David Wiegand is head of Sculptureworks Inc., a Texas-based concern that represents an international consortium of sculptors, Glen included. He compares the African bush-dwelling Glen to Remington in his calling to immortalize, in art, wildlife whose present is as uncertain as its future.

“He is documenting something that might not be there for our children and our grandchildren,” Wiegand says of Glen’s array of elephants, lions and baboons. “Robert’s got that in his mind, that he must make his work stand for all time. And this is a fellow who is invested in making it right; he’s a sculptor’s sculptor.”

Glen’s penchant for realism found a like mind and manner in Carpenter. He gave Glen carte blanche concerning the artist’s rigorous standard for research. Glen traveled to Spain to observe a herd of Andalusian horses, believing those animals most likely today to exhibit the conformation of American mustangs of old. Countless drawings and models later — with each horse requiring two tons of clay — Glen traveled to England for the bronze casting, a period that stretched for more than two years.

The horses, which are one-and-a-half times larger than the size of the actual animals, are represented from youth to age, with the band containing two stallions — one triumphal and massive at 6,000 pounds — five mares and two foals. The sculpture is in relief in a plaza built of Texas pink granite, one reason Williams Square has been the object of both national and state architectural awards. And the site still collects accolades as a planned community conceived at a time when such developments were relatively rare.

Yet the concept of a commemoration in the public domain, the act of establishing art in urban areas, spans the centuries, says Elise Bright, professor and coordinator of the urban planning program with the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning at Texas A&M University.

“In Europe, there are many cases where art is featured in a park or statues in public squares,” she says. “In this country, it became less common with the development of suburbs and populations spreading out from the urban center. In the ’40s and ’50s, developers weren’t budgeting for art, they were building houses. But today we’re trying to recreate spaces like the old urban neighborhoods — and art is part of that.”

And art is a part of everything that is lasting about civilization, predating the metopes of the Parthenon and designed to outlast the hour on stage allotted to the individual. So keen is Glen to leave nothing to posterity that is undeserving of it, he has been known to destroy a model even as it was being packaged for the foundry.

“It’s better to scrap it and start again from scratch than to keep working on something that hasn’t got it,” he says. “When I look at a sculpture, I am analyzing its essence. But you learn as you go. You look at your work and say, ‘What can be left out? How can I say something with as little as possible and still have an impact?’ When you can answer that, when you can achieve it, you will have a sense you’re on the right road.”

That road has been long and circuitous and sometimes fatiguing. But Glen has emerged refreshed by a lifestyle that dispenses with modern conveniences in exchange for a deeper understanding of his relationship to the universe. While the leisure activities of many fasten on ways to escape the world, Glen is intent on immersing himself in it.

“Anyone involved in art can’t rely on gimmicks,” he says. “Animals have something to do with who we are and where we come from. To live with them and among them is to begin to know them. And, in the process, you begin to know yourself.”

Laura Zuckerman lives and writes in Salmon, Idaho. Her work has been featured in a range of publications, from The Washington Post to Country Magazine.

- “Buffalo Bull” | Bronze | 7 x 23 x 11 inches

- “Lion Lying” | Bronze | 8 x 16 x 8 inches

- Glen stands with The Mustangs of Las Colinas, which brand the complex known as Williams Square and which rival the Alamo as one of the most visited sites in Texas.

- “Pair of Elephants” | Bronze | 10.5 x 20 x 9 inches

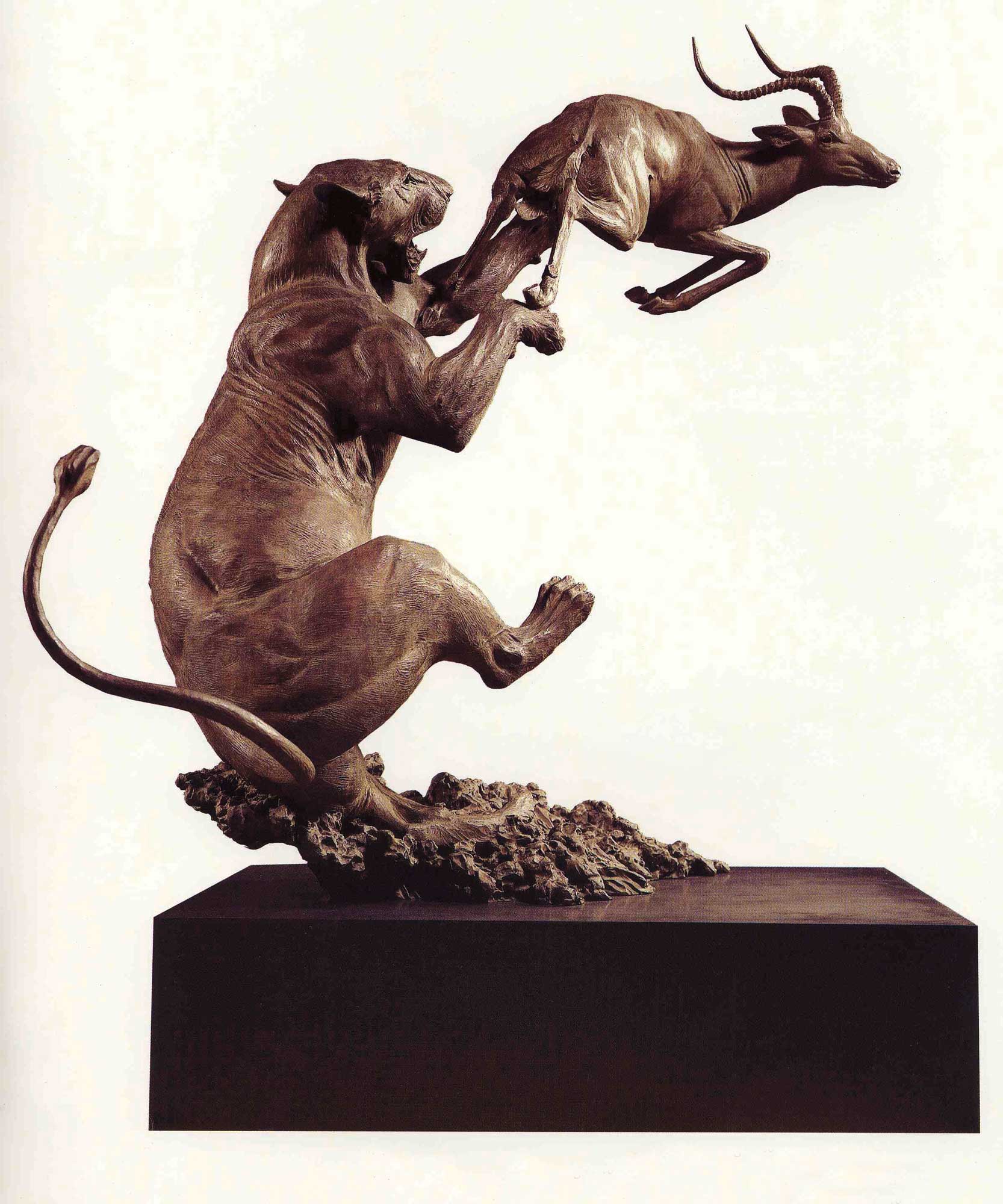

- “Close Shave” | Bronze | 128 x 75 x 45 inches

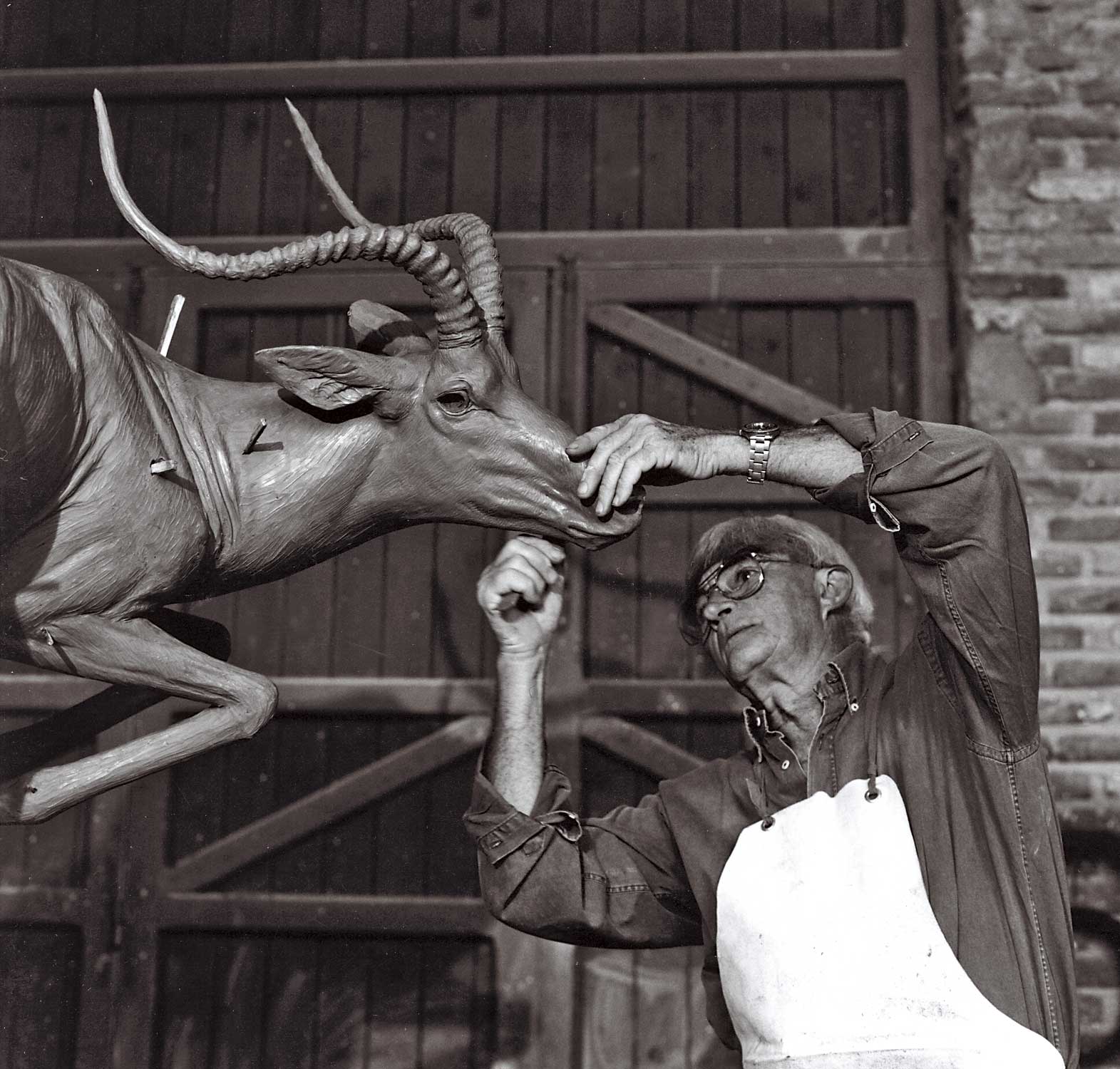

- Robert Glen works on the plasticine model of a lifesize impala. Photograph by S. Sabella

- “Sable” | Bronze | 28 (tip of horn) x 21 inches

- “Young Somali Girl Chasing Camel” | Bronze | 12 x 20 x 7 inches

No Comments