01 Dec Altered State

BEAUTY IN NATURE: Is it sublime or foreboding and subliminal? Is it real or mirage, fragile or resilient, sacred or profane? Are the images we see before us cause for sensual comfort or alarm?

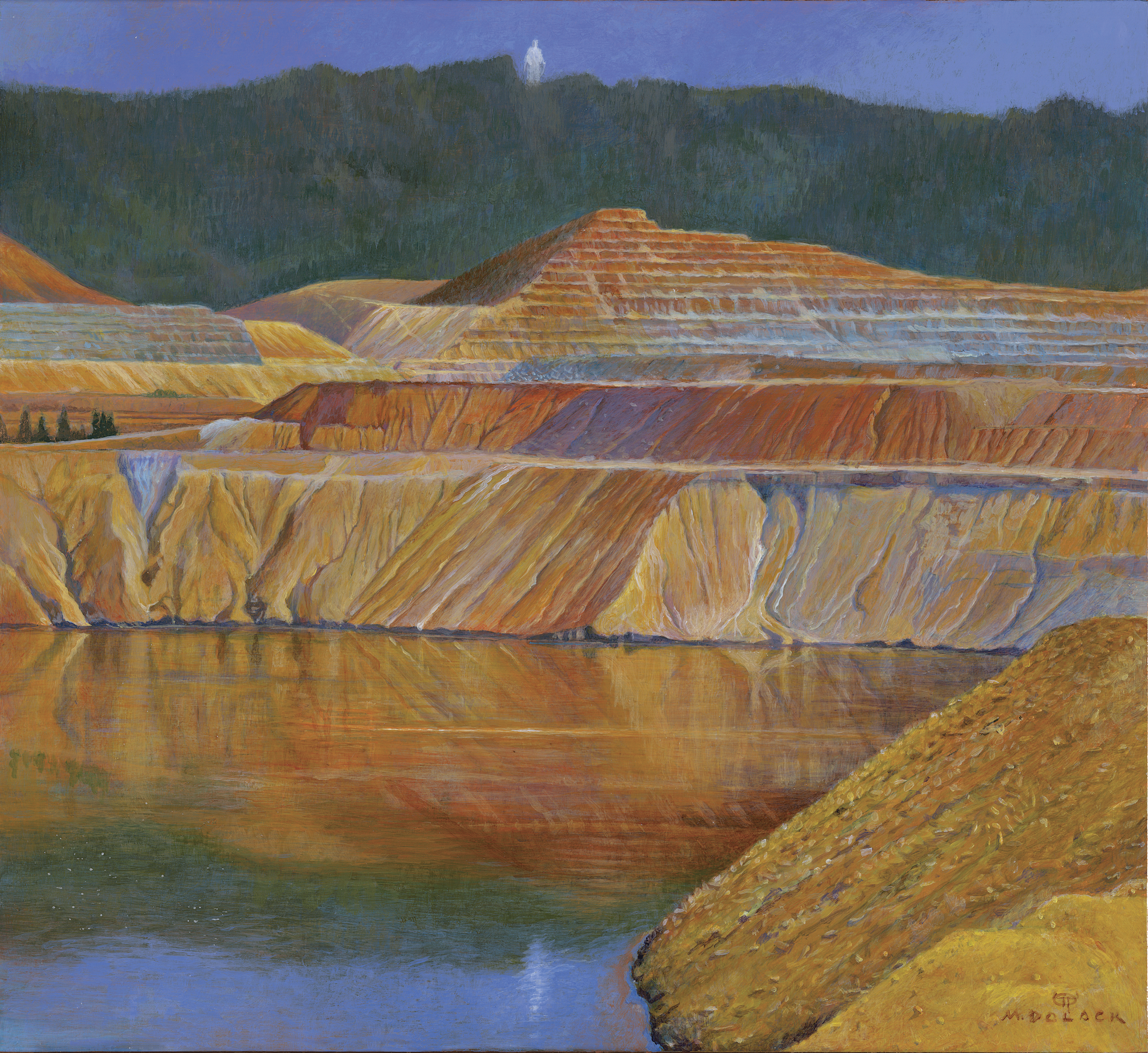

In one of several new Monte Dolack paintings, consider this scene that might easily be mistaken for a portrayal of Yellowstone’s geothermal wonderland — an interpretation perhaps of the national park’s awe-inspiring travertine terraces at Mammoth Hot Springs?

Yet step closer to Dolack’s ironic illusion and one discovers that the subject is not what it appears. In fact, it’s a view of the notorious Berkeley Pit, a federal Superfund site in the copper mining town of Butte, Montana, among the most toxically contaminated, human-dug craters in America.

Although the orangey stew of surface water reflects the purity of a blue billowy sky above, Dolack invites us to ponder the starker dual truth. Such is the milieu of Dolack’s solo exhibition opening in January 2014 and running through April at the Holter Museum of Fine Art in Montana’s capital city of Helena.

Titled Altered State: Musings on the Contemporary Montana Landscape with Paintings and Constructions by Monte Dolack, it is arguably the most important and ambitious show of the artist’s career.

“I’ve been struck by the dynamic tension between Montana’s diverse natural landscape and its collision with civilization, industry and development. Most intriguing is how both come together through the elemental forces of fire, water, wind and land,” Dolack says from his studio near the loom of the Rattlesnake National Recreation Area and Wilderness outside of Missoula.

Some of the dichotomous relationships that Dolack explores deal with the legacy of copper mining on the Clark Fork River, at Silver Bow Creek and Milltown Dam (recently torn down to let the Clark Fork flow free again); the presence of a massive oil refinery in Dolack’s hometown of Great Falls on the banks of the Missouri River where Lewis and Clark walked on their famous expedition; the epic earthmoving that occurred along Mike Horse Creek, a important tributary to the Blackfoot River made immortal by writer Norman Maclean in A River Runs Through It; and the flowering of massive wind turbines on the prairie yielding their own surreal aesthetic.

For good measure — and intended by design to heighten the jumble of mixed metaphors — Dolack also garlands Montana’s big open with the trappings of coal trains moving like serpents through “the Last Best Place,” and missile silos housing doomsday nuclear warheads; geometric patterns of timber clear-cuts; dinosaur bones reminding us of long-ago extinctions; and the emerging impacts of climate change.

For Dolack, a Treasure State native son who is something of an artistic folk hero, Altered State represents not a departure from previous, more sanguine and satirical work but an assertion of his identity as a fine artist and visual provocateur.

“Monte is one of Montana’s best-loved artists for many reasons,” says Arlynn Fishbaugh, executive director of the Montana Arts Council. For the generation that experienced the first Earth Day in 1970, Dolack literally turned the cause of conservation into a fashionable art form. No other painter in the West arguably has worn the modern environmental ethic so passionately on his sleeve and with such courage and reach.

“Monte Dolack’s lifetime of work as master poster artist, illustrator, and painter have defined a graphic style and visual identity for Montana. He celebrates his homeland’s iconic vistas, its natural monuments and the creatures that inhabit them: trout and bison, mountain goats and kingfishers, bear and wolves, and the occasional cowboy or fisherman. His colors are as startling as a prairie sunset, as vivid as a field of wheat. His shapes are realistic, but not quite real, tending toward the mythic. And his passion for preserving the glories of his homeland is tangible in every poster, every painting,” says Annick Smith, the noted Montana writer who co-edited the acclaimed anthology The Last Best Place and co-produced the Hollywood movie A River Runs Through It with Robert Redford.

“But Dolack is never preaching, never boring,” Smith adds. “He salts his visions of living on the fringes of the wild, as most Montanans do, with a sense of humor and paradox — mallards in bathtubs, penguins in the fridge, a huge rainbow trout on the living room couch. Montana is a state that loves stories, and Monte’s picture stories are about movie stars and ranchers, fishermen and couch potatoes, bears and great blue herons and symphonies and firefighters. They are entertaining and ethical and crystal clear, like the best loved stories of what we believe is the last best place in the American West.”

Dolack’s lithographs and posters today adorn the walls of homes and businesses from the mountains to the prairie. Over the years, he has helped to raise millions of dollars for groups involved with wilderness preservation, safeguarding imperiled species, protecting scenic open space and ensuring that trout streams — his favorite venue of escape — continue to run pure and clean. He’s also been a major booster of public television.

Calling him a “populist” in the same way that Charles M. Russell created works common people could relate to, Fishbaugh notes that Dolack, because of a line of commercial products, has helped make contemporary art more accessible to the masses.

“He’s done a great deal to help people develop into authentic art collectors,” she says. “Many may start with a Dolack card or poster. Then they buy a print and eventually they purchase an original painting.”

Altered State, however, reveals another side of Dolack — that of serious painter who possesses technical skill far beyond the gifts of graphic design with which he is closely associated.

“These new works don’t look like the pretty posters that most viewers are accustomed to,” says Caleb Fey, director of the Holter Museum. “They’re nutty and fun and whimsical, yes, but they emanate deeper, darker narratives. When I first saw them in his studio, I looked at Monte and said, ‘Really, these are coming out of you?’”

Dolack says the ideas have been germinating a long time and contemplated at length with his wife, the nature painter Mary Beth Percival. Their friends assert that finally, at last, Dolack’s vision and technical prowess will be fully appreciated.

Dolack loves to experiment with incorporating found projects into his surfaces, combining mixed media and exploring different kinds of surfaces. He even works three-dimensionally in Pop art sculpture. His piece, Tyrannosaurus Wrecks, is constructed of Hot Wheels toy cars.

In Altered State, many of the flatworks are painted on copper panels both to achieve a more interesting iridescent effect, and as a symbolic reference to the legacy of Montana’s Copper Kings, who amassed Gilded Age fortunes from the ore they disemboweled at Butte — and the gargantuan environmental messes they left behind.

There’s added significance for Fey, who previously worked at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., before taking his current job. Ironically, he notes, the Corcoran’s Clark Wing is named after Butte mining titan William Clark, a museum benefactor and a man known for trying to buy himself a seat in the United States Senate. “Dolack’s show helps to bring the circle back around,” Fey says. “His imagery invites us to contemplate the past, try to make sense of where we are, and to look forward.”

In 2014, Dolack’s profile will get another national boost. He’s been commissioned by several American conservation organizations to paint the commemorative poster for the Wilderness Act of 1964’s 50th anniversary. Just a few years back, Dolack received special recognition at a retrospective sponsored by the United Nations when 24 works were used to highlight its “International Year of Trees” celebration in Geneva, Switzerland.

Dolack, whose art has been likened to the literary device of magical realism, is devoted to the principle that art can serve as a mirror held up to society. But before humankind can make an honest assessment, it needed to confront the mythology that is part of its storytelling. Dolack’s richest vein is the construct of Manifest Destiny and the false promise of limitless resources.

The artist’s connection to the Montana history he’s excavating is not abstract. His father worked at the old Anaconda copper refinery in Great Falls and Dolack himself found employment there as a laborer during its last legs when he needed to make money for college at Montana State University and the University of Montana. He proudly notes that his grandfather, Steve Dolack, immigrated to America and toiled as a coal miner in Belt, Montana.

“Who is Monte Dolack? A gentle soul who would defend the people and places he loves with the heart of a lion,” says Emily Heid, a surgeon and ardent Dolack collector.

“Monte doesn’t see himself as a landscape painter, per se. His work always evokes emotion — sometimes joy and often a sense of melancholy, but not sadness, she adds. “Seeing his work, I often long to walk into one of his settings and feel the magic he instills. He’s an artist with an incredible sense of how all things big and small are vital to nature.”

That sense of interrelatedness, of sentience uniting a spirit of all living things, is important in Dolack’s thinking. He invokes Leonardo da Vinci, the template for a Renaissance man who incorporated art, philosophy and science into every act of self expression.

“I am interested in and influenced by the fusion of art and science, which is vital to the time we live in,” Dolack says. “Governance can be good or bad for those who are governed. It can be informed by the best information and science available or by opinions simply informed by others’ opinions and that has the potential to put humanity down a perilous path.”

Dolack and Percival have been inveterate global travelers, their favorite destinations being art museums and the archeological sites of ancient civilizations in the Old and New worlds. On his bookshelf, not far from his painting easels and drawing boards, are The Power of Myth and The Hero With A Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell, Collapse by Jared Diamond, The World Without Us by Alan Weisman and National Geographic photographer James Balog’s documentary “Chasing Ice.”

Dolack’s brushstrokes are informed by their cautions firing the synapses of his brain. “I have worked toward achieving a balance of tension and ambiguity, and have tried not to be too didactic or preaching,” Dolack says. “At times a gentle humor or narrative mixed with a bit of the surreal or the magic derived from observing nature and being infiltrated by it.”

For him, what does the perspective of being a Montanan hold that the rest of the world might heed? “Respect for nature and the hard lessons learned from our huge industrial mistakes of the late 19th and 20th century,” he says. “Not all Montanans share the view that healthy nature is priceless, but more and more people do. I just want to join them by providing a little visual encouragement. By coming together in a little meaningful work, all of us can leave a better Montana, and a better West, for the children of the future than the one we inherited.”

- Artist Monte Dolack works on “Tyrannosaurus Wrecks”

- “Winds of Change” | Acrylic on Copper | 11 x 12 inches

- “Fossil Fueled” | Acrylic on Copper | 9 x 12 inches

- “Suspension of Belief” | Acrylic on Copper | 18 x 20 inches

- “Superfund River” | Acrylic on Copper | 9 x 10 inches

- “Silver Bow Creek” | Oil on Copper | 9 x 10 inches

No Comments