11 Mar Art as Testimony

IN THE WIZENED, PIERCING GAZES that appear in David Kassan’s oil paintings of Holocaust survivors breathes an intangible ghosted presence draped with the knowledge of our collective history. These life-sized portraits bear witness to one of the darkest moments in humanity’s past. Yet, they also exude a sense of endurance, courage, and beauty.

For the last few years, Kassan has painted portraits of Holocaust survivors, which continues to be the singular focus of his career. Blending paint and testimony, his work translates the experiences of survivors into something tangible. When confronted with this work, it’s hard to look away without needing to know the stories behind it. Kassan completed 20 life-sized portraits for last year’s solo exhibition at the USC Fisher Museum of Art in Los Angeles but wants to create 20 more with an eye toward more museum shows.

“I’ve met with 40-some survivors right now, and I have video footage of our meetings. The L.A. show represented about half the survivors; I’ve been trying to get to them before they pass away,” Kassan says. “They’re all in their late 80s or early 90s, so I really feel the pressure to get this done.”

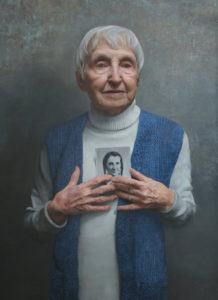

Raya Kovensky | Oil on Panel | 40 x 27.5 inches | 2017

Kassan began painting and interviewing survivors in 2013, when an Israeli collector asked for a portrait of his mother. “I told him that I don’t usually do commissions,” Kassan says. “Then he told me she was a survivor of the Shoah. I immediately told him I would do it, but it won’t be a commission; you can buy it, but I want control of it.”

The collector did not end up buying the painting, but Kassan gained more than a single sale — he found his calling. For the next five years, he traveled to Holocaust survivors’ homes collecting stories and painting them in a “social documentary” style, funded in part by donors of the University of California’s Shoah Foundation and in part by his own fundraising.

“David is a painter who has an Old-World, traditional style,” says Dr. Stephen Smith, executive director of the Shoah Foundation. “What struck me was the vivid imagery, and I immediately recognized what he was doing as an act of testimony. I spend a lot of time with Holocaust survivors, and there’s something particular about the way they appear.”

Edward Mosberg | Oil on Panel | 30 x 22 inches | 2019

When Smith met Kassan, the artist wasn’t exactly who he expected. “I’ll be honest, I expected a 70-year-old, not a 40-year-old with a ponytail,” Smith says. “This young person had the maturity to paint people whose lives were so impacted. … [He conveyed] the essence of their characters, which I knew so well. I saw an individual who dedicated years on his next brushstroke — a purist and a perfectionist — but at the same time, someone who recognized it was worth taking his time with this very distinct group of people to create images in perpetuity. The thing about a painting is that you don’t throw it in the trash.”

Kassan plays the interviews he recorded while painting to inform the work and to keep the subjects alive in his mind. He also hopes to one day use the videos in a documentary film. “Imagine having more information on who the Mona Lisa was? It helps the painting come to life a little more. Especially the people I’m painting right now. The interviews are an excuse to get to know the subjects a bit better,” he says. “The testimony is important for the people I’m painting. I’m in their homes, and it’s inspiring because I meet with their families and they show me photos from their past.”

Kassan begins with a charcoal drawing to allow himself to be as expressive as possible. Then he transfers the drawing onto a sanded acrylic mirrored panel, which adds luminosity. “From there, I do an oil glaze; then, I put the tracing where I want it on the panel,” he says. After these initial steps, he builds a tapestry of color by implementing a series of small strokes, a technique called broken color. “Broken color interacts and allows you to see all the different hues that make up skin tones,” he adds. Kassan also prints a photo of his subject that’s the same size as the finished work, and each portrait is life-sized. “A lot of the time, I paint [the canvas] upside down and sideways, because I’m not that tall. They’re 8-foot panels. I love abstracting everything to see the shapes, and it’s easier to paint upside down and sideways,” he says.

John Adler | Oil on Linen | 27 x 34 inches | 2018

Kassan doesn’t enhance the features of people, as doing so goes against his documentary-style effort. “I paint very raw; I don’t have a beauty filter,” he says. “The paintings I want to make are very honest. It’s hard to do that when people want to be changed [to look better]. I find it very soul-stealing. A painting is something I love doing, and I don’t want any negativity in that process. It’s my sacred space. As a painter, I’m not making a product.”

Beau Maxwell, owner of Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles, represents Kassan on the West Coast and has observed the progression of his work. “David is on the fence between two worlds: the Contemporary Realist and Classical Realism,” he says. “But even with those, he pushes them to the point where it feels very contemporary. He’s just gotten better and better over the years. A lot of the time, an artist searches to paint what his mind sees. David turned a page in his ability to do that and in his willingness to take a step back, as he did with the survivor series. That is not an easy sale, but it’s something that will hold its own in history. It’s what the world needs to see at a time when the world needs to see it.”

At the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, Kassan meets with the Holocaust survivors that he painted for Bearing Witness. Photo by Andy Romanoff

When weighing his portraits against photography, Kassan points out the advantages of paint: “It’s a great medium to capture humanity,” he says, adding that he wants the emotions to come from the sitter. “But it also comes from me, the way I chose to show the subject and the background, that’s all my handwriting on the painting. I want people to have a conversation with these paintings.”

After graduating with an art degree from Syracuse University, Kassan moved to New York City. “I always wanted to be a figure painter, but I wasn’t good enough yet,” he says. At first, he worked as a graphic designer, but after September 11, he decided to paint full time and enrolled at The Art Students League of New York, “working from morning to night” for five years. “I was doing it like it was my job,” he says. “I was living way below my means. In 2006, I became a stay-at-home dad, so I switched to taking night painting classes. Then I got a grant to study in Italy for two months.” While there, he studied sculpture, and by the time he returned to New York City, he felt ready to tackle the figure.

Hanna Pankowsky | Oil on Linen | 35 x 25 inches | 2018

After moving from Brooklyn to Albuquerque, New Mexico, Kassan feels himself following in the footsteps of one of his artistic idols, Ashcan School artist Robert Henri. “The Ashcan School inspired me when I first moved to New York, and they’re still inspiring me,” Kassan says. In 1916, Henri started to spend time in New Mexico, and in the following years, his enthusiasm for the landscape and the people brought many other artists out West. Now Kassan understands that connection. “I see a lot of the same textures in the urban environment of the West that I saw in New York, and I connect with the people; it’s kind of an ethical and moral perspective that I respect,” he says.

In New York City, Gallery Henoch has represented Kassan since 1999, when he painted cityscapes, building façades, and intersections of city life. Andrew Liss, assistant director at the gallery, sees Kassan as an important painter and as the only contemporary painter combining live interviews with historically significant subjects.

“From a capitalist point of view, it’s a money loser, but these are not paintings made to fly off the wall. They’re made to be influential. They speak to who we are as a society, where we’ve come from — that linkage of memory — and not allowing that memory to be lost. This is the high-art component he provides. The light and life force energy in these paintings is profound. These people are not supposed to be here,” Liss says. “There’s that standard phrase people use about buying portraits: ‘I don’t want to hang someone I don’t know.’ But a more evolved collector understands they’re buying a certain amount of talent as well as the historical resonance. David’s portraits speak powerfully with an emotional element that makes the viewer want to come up close and find the wisdom hidden there.”

No Comments