10 May Art Meets Architecture

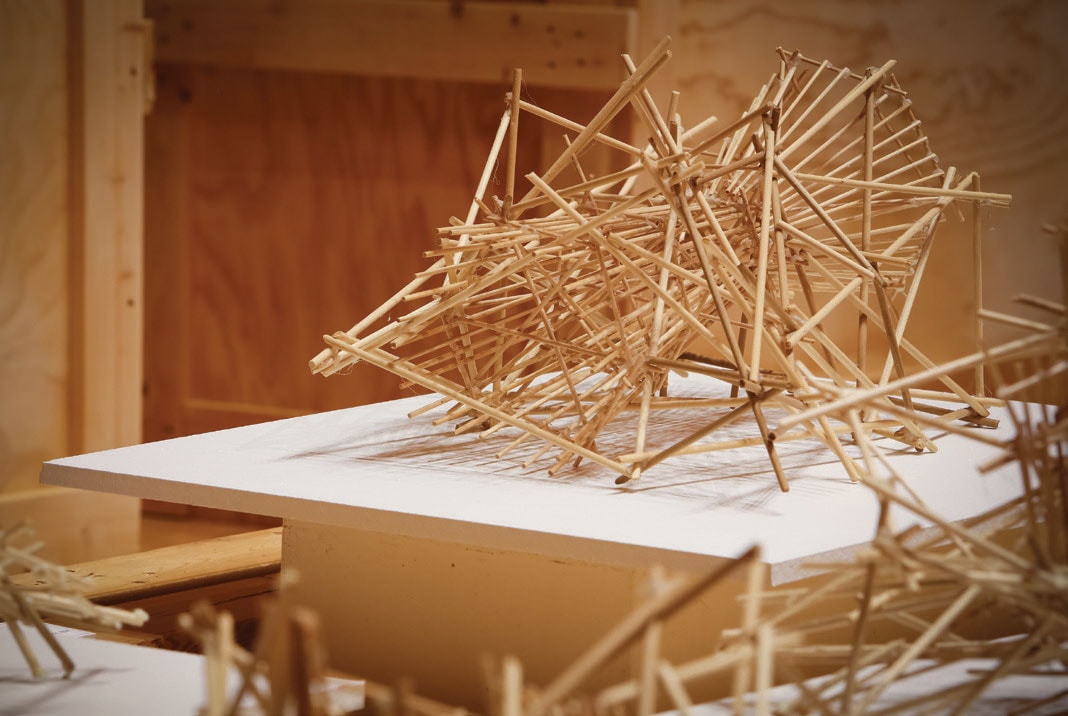

Talasnik at work on The Hive, which expresses both architecture and sculpture.

LAST SEASON, THE TIPPET RISE ART CENTER finished its year with an extravaganza encompassing spectacle, performance, and fire. Sculptor Stephen Talasnik, creator of permanent land art installations at the Fishtail, Montana, sculpture park, constructed The Hive especially for the 2018 finale. Inside The Hive, he allowed space for composer and cellist Ilse-Mari Lee to perform a piece she specifically wrote for the event in addition to Bach preludes. The performance culminated in the ignition of the structure outdoors with flames engulfing its organic form, closing the circle on Talasnik’s architecturally inspired piece.

For The Hive, the flat reeds were woven around a wooden scaffolding and secured into place according to Talasnik’s vision.

Talasnik’s installations have stood within the contours of the land at Tippet Rise since the art center opened in 2016, explain founders Peter and Cathy Halstead, adding that he’s “the sculptor of movement and density, with Escher’s imaginary dimensions, and the string prisons of Italian artist Piranesi turned into three-dimensions.”

To create The Hive, Talasnik used materials he discovered years ago while in Thailand, including flat reeds for the rectilinear frame. “That indoor sculpture show was Tippet Rise’s first foray into indoor sculpture activity. Everything else I create is land art,” Talasnik says. “I learned about sculpture by looking at architecture. I learned about drawing by copying architectural drawings.”

His work, intuitive and complicated, conveys a loose, conceptual frame suspended between shelter and the idea of sanctuary. The organic form of the piece speaks to the narrative of nature and discovery.

“When I first came to Montana, I was interested in the horizontal scale of everything,” says Talasnik, who currently resides in New York City. “Scale is different here than on the East Coast; the finite versus the infinite. Before coming here, my height restriction was the height of a building. Everything was based on an architectural scale.”

Moments before a concert by composer and cellist Ilse- Mari Lee began in the Olivier Music Barn at Tippet Rise, the lights dimmed and the sculpture, illuminated from within, dra- matically came to life.

When commissioned for his first sculpture at Tippet Rise, Satellite #5: Pioneer, he established a dialogue specifically connected to the land. In the creation of The Hive, he wanted to make something reminiscent of airships, something light and ethereal.

“I combined a rectilinear space frame used in architecture,” Talasnik says. “Simply put, it’s a loaf of bread and every slice is a variable. If you were to stretch the bread apart or slide a dowel through it and stretch it, you could make it bigger.”

A detail of Talasnik’s Satellite #5: Pioneer

Various angles of The Hive, which was lit by LED lights. Lee performed Bach preludes and an original composition during her concert, part of which took place inside the sculpture. Photos cour- tesy of the artist

The Hive asks viewers to participate in the finality of the piece. Talasnik sees his work as “incomplete” in order to achieve his vision. “Everything I make, including The Hive, has a sense of the unfinished,” he says. “But what I learned from drawing, unfinished can be complete. It’s more important to make something complete than to finish it because that engages the viewer. To be unfinished establishes a triangulated dialogue with the artist, the piece, and the viewer.”

Part of his process is to instill time limitations. By working with self-imposed constraints, his focus heightens while forcing himself to come up with unique and unforeseen solutions. “Every piece I do has a time limit,” he says. “When dealing with problem-solving, I’ve found that solutions are subjective and objective. Subjective solutions tend to have a multitude of solutions. Objective problem-solving tends to find a more perfect solution. If I combine the two with the constraints of time, I can push my creativity. This process shows without disclosing the mystery.”

A maquette of Satellite #5: Pioneer, Talasnik’s permanent land art piece at Tippet Rise.

Before starting the piece, Talasnik selected the materials with an intention of what The Hive might become, but the artist had no notion of its size. He doesn’t work with preliminaries. Instead, he draws.

“I had no preconceived notion of what it would look like,” he says. “I just had the confidence to know I could get there. That’s what I’ve acquired through my work. The lighting was a new component for me. I knew I wanted somebody to sit in there. I didn’t know what it would do to the acoustics. I’ve always envisioned my work as seamless performative art, such that it is not a stage set but a collaborative piece between artists.”

That is exactly how Lee, composer and cellist, felt when she performed inside The Hive. She created a solo overlaid with a digital soundscape specifically for that evening.

“When I was asked to perform, I was excited,” she says. “I knew immediately I wanted to write a solo cello piece, and I wanted to play Bach.”

Satellite #5: Pioneer was designed to reference NASA probes of the lunar surface.

Before entering the sculpture, Lee played six Bach preludes. “It is a concert I’ve wanted to do for a long time. It’s a huge undertaking, both for the artist and for the audience. But I knew I could take the audience through a whirlwind journey via the six preludes within the intimacy of the Olivier Music Barn,” Lee says.

Her original composition, Unearthed, merged with the digital soundscape to recall the feeling of being engulfed by a thunderstorm. “As a performer, I always feel so exposed up on a stage. What was so different was that I was in an organic structure, and I felt protected, enveloped, safe. I was in a magical realm,” Lee says.

The musician started the concert performance in absolute darkness and the light gradually grew brighter with time. “I wanted to write a piece from which the cello would emerge. I’m a film composer, and I wanted the audience to be immersed,” she says.

Lee felt performing in the Olivier Music Barn, within The Hive, and in front of an enraptured audience, was like being inside of her cello. “When I look back on that shared experience, as an artist, I think, that’s as good as it gets.”

No Comments