19 Oct Art Through the Lens of Science

WHEN AMERICAN PAINTER LANEY HICKS — best known by her mononymous moniker “Laney” — thinks about wildlife art as it’s been expressed throughout the ages, she sees patterns. Not only those inherent in the aesthetic of natural beauty and the brilliant, varied designs of creation. She also relates in spirit with those whose scientific orientation toward their subjects gives them a shared identity as naturalists.

The cave painters of Lascaux? Part of their veneration of animals involved a quest to understand other species. One could even say their curiosity was fired by the same passions as ours today. Let us also mention the ancient Chinese artisans, the Greeks, the animists of Africa and Australia and the residents of Babylonia.

Moving forward, there was Renaissance man Leonardo da Vinci. He built an artistic and philosophical bridge between the scientific quest for knowledge and fundamental truths about proportionality revealed in nature. Next think of Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus, who pioneered the system of binomial nomenclature that we use to classify species and who, when he went afield, carried a journal and sketchbook with him. Almost 30 years after Linnaeus passed from the scene, a giant of a naturalist, Charles Darwin, was born and his theories shook the foundations of how humankind explains Earth’s biological diversity.

Beginning this autumn and remaining on display until spring 2014, the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, is featuring a much-anticipated exhibition, Darwin’s Legacy: The Evolution of Wildlife Art. Although he gets prominent billing, the iconic forerunner of evolutionary theory and natural selection is just a springboard for showcasing works by historic naturalists and contemporary living artists counted among the finest of our times.

“Taking a historical look at Darwin’s influence and tying it into the work of artists living today who continue to have close associations with the scientific field struck a chord with us,” says Adam Duncan Harris, chief curator at the museum. “At the same time we first conceived of it, we were in the midst of acquiring a masterpiece by Joseph Wolf [1820–1899], widely regarded as the preeminent British animal artist of his era and, interestingly enough, an illustrator of one of Darwin’s later texts. So, many threads began to come together to form a coherent whole.”

A masterpiece indeed. Wolf’s recently acquired work, Gyrfalcons Striking a Kite, painted in 1856, is a tour de force, arguably as fine as an avian predator-and-prey scene portrayed by Bruno Liljefors (whose work is also featured in the exhibition).

As excited as Harris is, he credits much of the impetus for the exhibition to Laney, who has been plying the intersection between art and science for half a century. “The main inspiration for this exhibit was a stimulating exhibit proposal from Laney,” Harris explains. “She had read and spoken with Diana Donald about her book, Endless Forms: Charles Darwin, Natural Science, and the Visual Arts. She was interested in the topic from her own perspective as a contemporary artist who is influenced by current science and pays careful attention to recording her subjects in a naturalistically accurate fashion.”

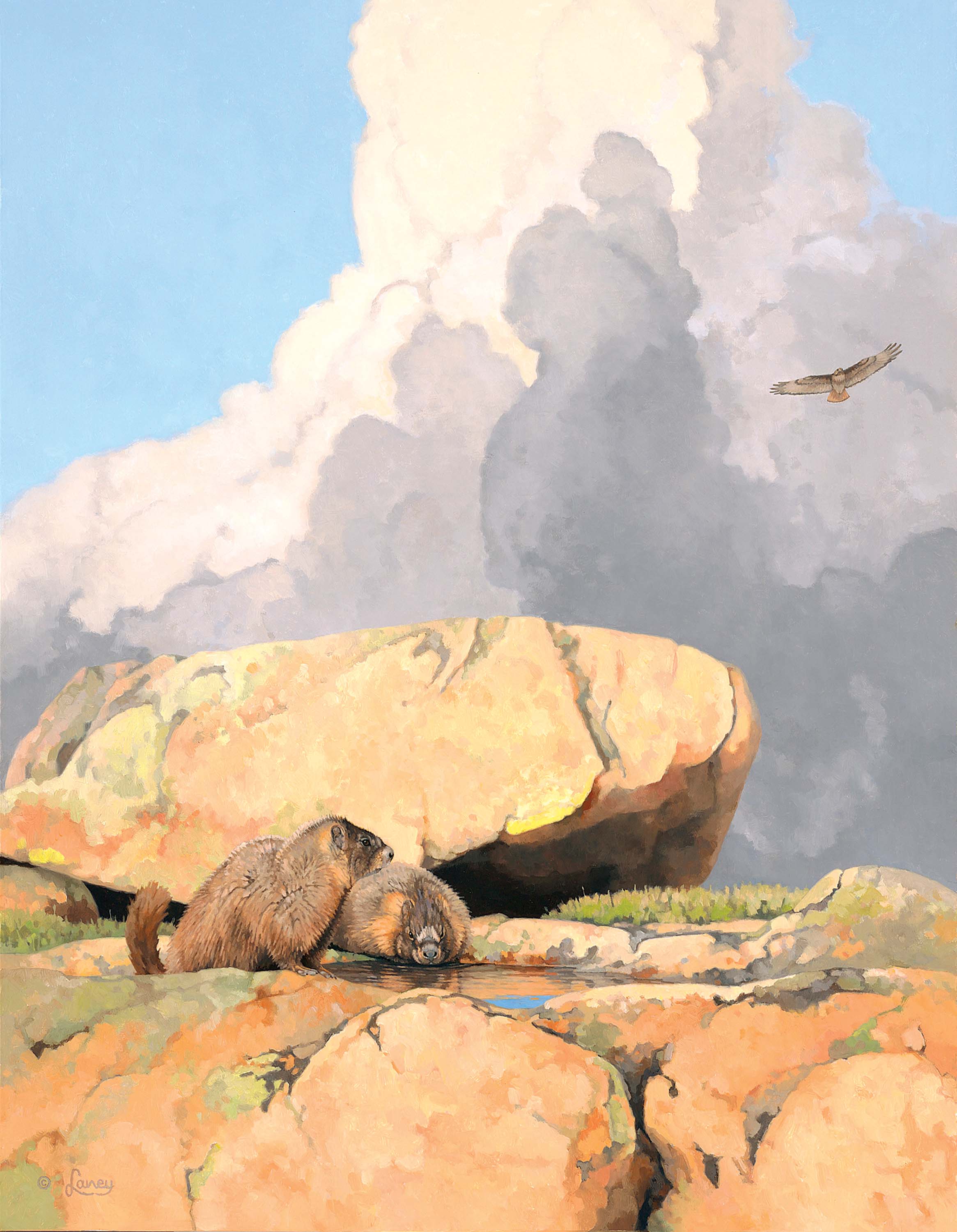

Laney is not an artist with a slavish devotion to merely rendering wildlife, replete with rigid anatomical exactitude and a style of photorealism that seeks to present every hair or feather on an animal’s back. Early in her career, the Colorado native completed an assignment as a scientific illustrator after graduating from the University of Denver, producing drawings for textbooks circulated among millions of people.

Just as species evolve, so, too, did Laney’s style. While her work is representational and realistic, step closer and one can appreciate her skill in crystallizing abstraction into visual fine-art narratives that are both accessible and evocative.

From her studio near Crowheart, Wyoming, within sight of the Wind River Mountains, she has attracted critical praise for her striking compositions, her own assertion of palette and daring approaches to subjects. She’s won numerous awards, had pieces included in traveling exhibitions and her works are part of permanent museum collections.

Laney has spent a lifetime studying body language and deciphering its meaning. In Wyoming, she lives in a wild neighborhood where grizzly bears and wolves inhabiting the surrounding mountains in growing numbers have affected the elk herd and moose numbers. She nurtures a covey of chukars that have become dinner for raptors and bobcats, leaving her with ambivalent feelings about those who would say the chukars are expendable.

Her belief that all living creatures possess differing levels of awareness gives Laney company with famed scientist and thinker E.O. Wilson of Harvard University. In fact, Wilson has helped to popularize the tearing down of academic silos and approaches to learning that have kept art, science and spirituality at arm’s length from one another. Like Laney, he says they are all interrelated.

In an interview last year with Wildlife Art Journal, Laney said the catalyst for her becoming a naturalist was her exposure to animals at home in Colorado and at her grandfather’s ranch. “The animals were always treated as equals. They had feelings and needs and, if given the chance, they wanted interaction with humans on certain levels. Being close to animals is easy for young people and most of the time adults make sure we get trained out of that easy association. My mother never did that and I am so grateful to her.”

Hers is not an endorsement of shameless anthropomorphizing. “I think one of the reasons that animal art is disregarded, many times, is that it gets over into a category I call ‘cute.’ It becomes sentimental and almost cartoonish. The naturalist, hopefully, is always true to scientific observation and respect for the difference between humans and other forms of life. We still have many areas where we overlap, but it is not true naturalist art if we make it into anthropomorphic scenes. We share with animals feelings like fear, love, raising young, anger, aggression, affection and territorial boundaries. These are easily observable.”

“The National Museum of Wildlife Art became interested in bringing art and science together in a way we had not explored previously,” wrote exhibit curator Jane Lavino in an overview of the show. “Laney epitomizes such an artist for whom the science and the art are inextricably twined.” Lavino notes that Nobel Prize winner Konrad Lorenz — a zoologist, ornithologist and ethnologist — had a huge impact on the artist. “Laney credits his writings about animal imprinting for giving her ‘the approval needed to treat the study of animal behavior as a legitimate adult occupation.’”

What began to fascinate chief curator Harris is how the basic concepts popularized by Darwin impacted the visual arts of his and later eras, he says. “There are legions of artworks that follow the ‘survival of the fittest’ storyline, not to mention the countless pieces that have made that phrase their title. As Diana Donald points out, artists following Darwin began to place a much greater influence on observing wildlife in the field, seeing and recording natural behaviors, then translating those observations into magnificent works of art back in the studio. That, for the National Museum of Wildlife Art, connects directly to Wilhelm Kuhnert, Bruno Liljefors and Carl Rungius.”

Further, if the avid avian art faithful is included it extends to the late Roger Tory Peterson (who invented a field guide series) and Don Richard Eckelberry (who had one of the last recorded sightings of the ivory-billed woodpecker), Francis Lee Jaques (who painted dioramas at prominent East Coast museums) and dozens of others.

“As we finalized the checklist we considered a wide sweep,” Harris says, noting that they found some interesting works by Carl Akeley, James Lippett Clark, Robert Rockwell and Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Akeley is legendary as both a sculptor and museum preparation specialist (taxidermist) who prepared some of the specimens at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

In addition to those artists of the past, Laney is among contemporary artists that include Swedish bird painter Lars Jonsson and American sculptor Bart Walter.

“This Darwin exhibit is novel,” Walter said. “I’ve never seen it done and never heard of it being done before. Since the museum is breaking new ground, I think it has wonderful potential.”

Walter grew up aspiring to be an artist, got a college degree in biology and then started working in clay and bronze with a more profound appreciation of how animal behavior can be brought to life. His portrayal of a chimpanzee, Contemplation, is featured in the exhibition and is part of the museum’s permanent collection. Among the private collectors of Walter’s series on chimps is renowned primatologist Dr. Jane Goodall. Walter hopes the exhibition will spur viewers, especially young people, to consider careers in conservation biology armed with graphite pencils, paints and sketchbooks in their backpacks.

When I asked Laney what she most savors, she said:

“I live in a relatively free country and still have the opportunity to live where I choose and can feel safe living in wild areas. The animals around me provide most of my satisfaction in life.”

Fortunately, collectors across the country don’t need to have the actual animals roaming outside their window. They have works by Laney bringing the wild inside to their wall.

- Joseph Wolf [Germany, 1820 –1899] “Gyrfalcons Striking a Kite” | Oil on Canvas | 71 x 59 inches | 1856

- Bruno Liljefors [Sweden,1860–1939] “Eider Ducks by the Sea”

- Lars Jonsson, “Rest After a Long Flight” | Oil on Canvas | 42.5 x 70.5 inches | 2000

- Bart Walter, “Contemplation” | Bronze | 25.5 x 20 x 22.5 inches | 1991 JKM Collection, National Museum of Wildlife Art

No Comments