07 Jan Born Storyteller

I STOOD IN THE WHITETHORNE KITCHEN, eating fry bread and honey. The autumn sun, cool and honeyed itself, spilled onto the countertops. It had been a hectic morning for Baje Whitethorne Sr., his wife, Priscilla, their son, Baje Jr., and 4-year-old granddaughter, Memphis. The house was full. A film crew was setting up cameras to interview Baje Sr. for a documentary about artists of the Southwest. After her shyness passed — like a cloud over the sun — Memphis was eager to show my new wife, Kimberly, and me her toys.

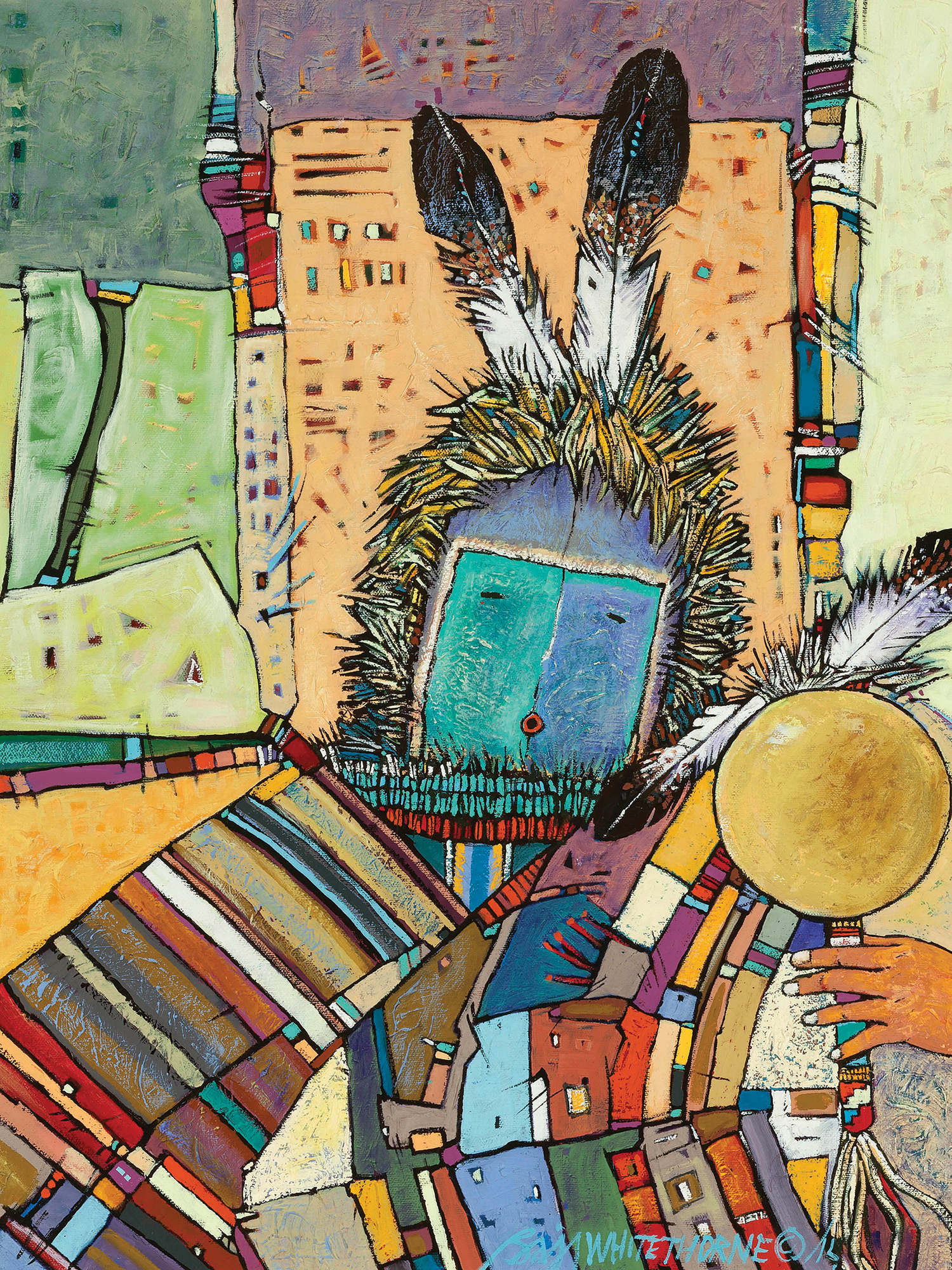

Amidst the chaos of the morning, the work of Baje Whitethorne Sr. hung around the house and in the studio like signposts toward tranquility, waymarkers for beauty. Baje is a natural storyteller; his paintings are steeped in Navajo tradition. For the artist, they conjure memories of childhood and tales from his grandmother that she had heard in her own youth — stories of heroes and legends of the Diné (Navajo) people. Baje paints to keep these stories alive.

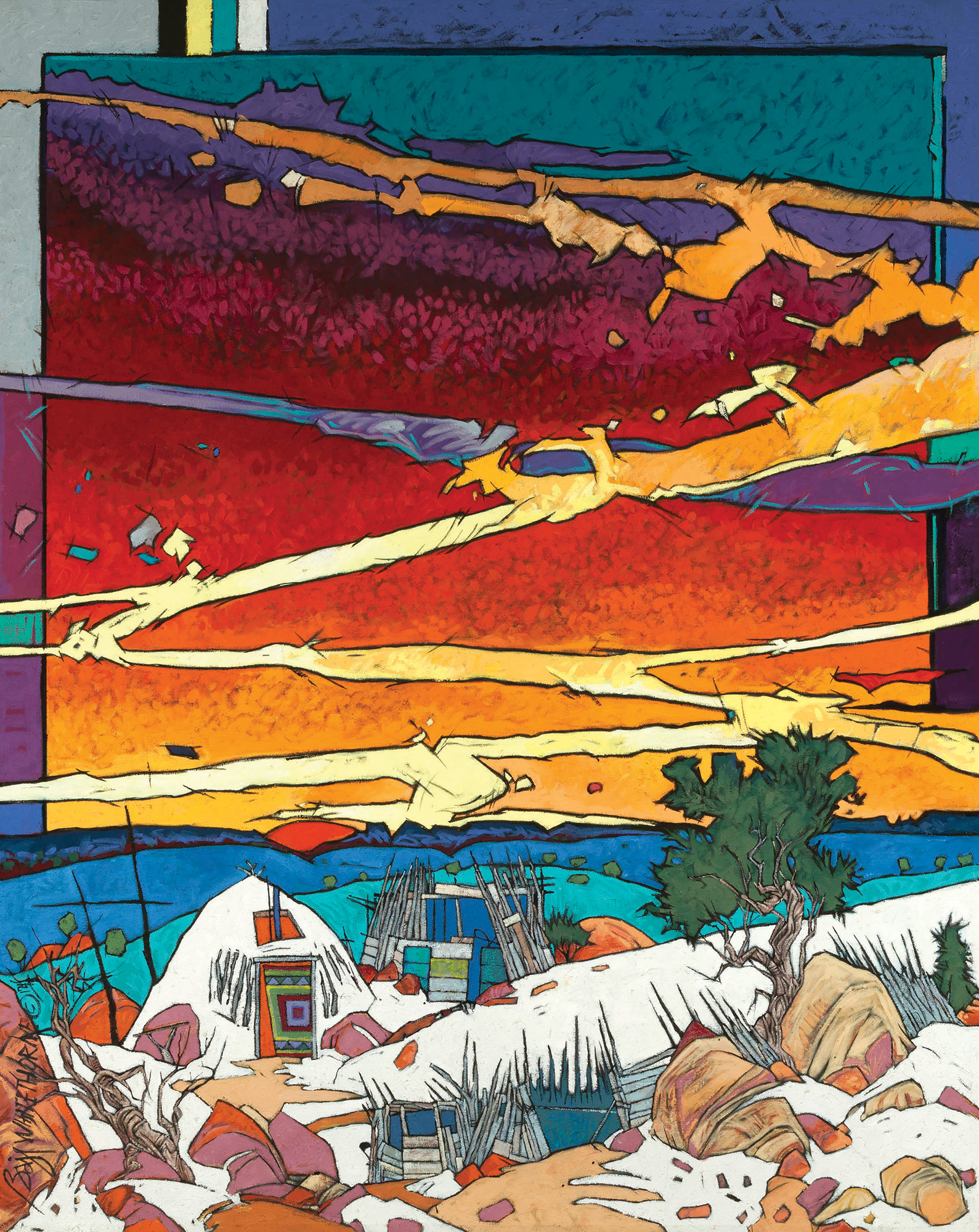

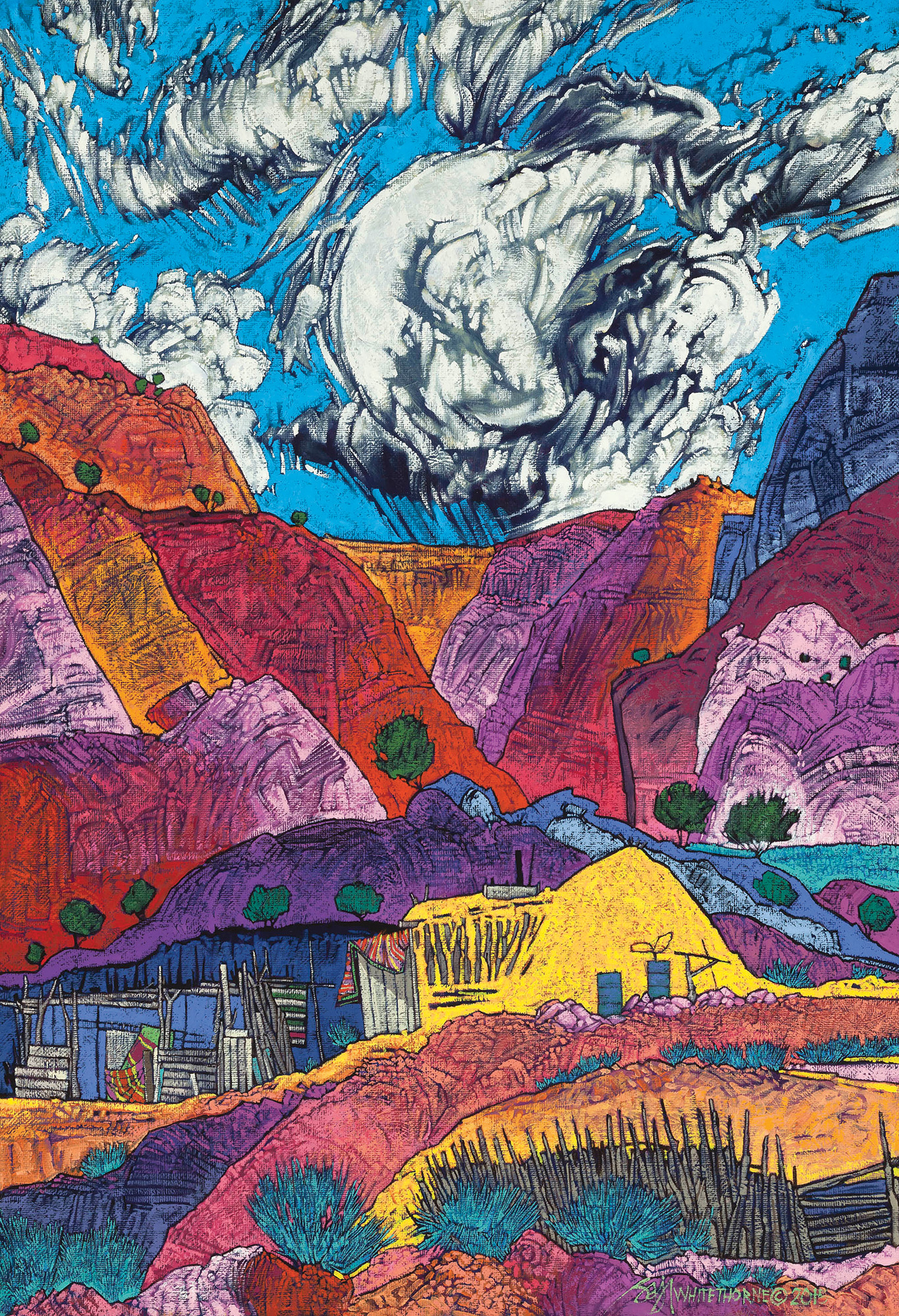

While each piece has its own mystical qualities, the imagery throughout his body of work is anchored in the real world. Besides his signature dirt-floor hogans, Baje depicts rough-hewn wooden fence posts, large metal oil drums used to store water, and sometimes an old coffee pot simmering on a campfire in front of the ancestral home. More often than not, the dwelling is nestled inside a canyon of tall cliffs, rendered in multiple colors with the quick, deft brushstrokes that are the artist’s trademark.

Where Baje’s work soars, though, is in his portrayal of the skies above. His clouds walk a virtual tightrope between form and spirit. The viewer loses himself in their structure. You want to climb into them; see what’s inside. They are at once anthropomorphic, shapeshifting before your eyes. But they are also edgy, even menacing, like a gathering storm.

Baje’s career owes its origins to the randomness of life. As a young man, in 1975, he was working as a boilermaker when he was seriously injured on the job. Laid up for almost a year and a half, Baje thought about his future and couldn’t envision returning to his old position. Instead, he began to wonder what else he could do with his hands. Eventually, he remembered how much he had enjoyed art as a youngster and one thing led to another until Baje discovered his true calling.

As his work developed, so did his philosophy about making art. “Everyone worries about a direction. I just go to the studio every day and look at my palette and sketches and find a place to begin. Change and growth are constant,” he says. From inside his home, where I have the benefit of seeing decades of works hanging side by side, I am witness to that growth.

Several years ago, I came across Whitethorne’s work for the first time at LoneDog NoiseCat, a now-defunct gallery located off Santa Fe’s famous Canyon Road. Despite the City Different’s reputation as the Indian art capital, it was one of the few local galleries that was Native American owned. Proprietors Ed Archie NoiseCat and Todd Lone Dog Bordeaux were serious artists in their own right. My visit got off to a shaky start when I praised the quality of the work in the gallery and NoiseCat asked, “What did you expect to find here? Paintings of Indian maidens down by the stream?”

After looking over several works by Billy Soza Warsoldier, the venerable painter associated with Santa Fe’s IAIA (Institute of American Indian Arts), I came across a few paintings by Baje Whitethorne and was immediately taken aback by their beauty. The originality of his iconography, his confident paint handling, the strength of his draftsmanship and the sheer vibrancy of his color were a revelation.

Two months later, while passing through downtown Flagstaff, I stopped for dinner at a restaurant called Criollo Latin Kitchen. To my surprise, the walls were ringed with paintings by none other than Baje Whitethorne. Though I discovered he lived only fifteen minutes away and I wanted badly to set up a studio visit, my schedule demanded I get back on the road first thing in the morning. The next day, as I drove Interstate 40 (part of the old Route 66) toward California, I couldn’t get his work out of my mind. Not long after, I attended Marin County’s annual Art of the Americas show. Sure enough, I found Baje Whitethorne conducting a watercolors demonstration.

Watching him paint was thrilling. He worked entirely from memory, drawing from a multitude of images that had been pressed into his subconscious by his grandmother’s folk tales. He uses those memories, too, I discovered, to write and illustrate children’s books. Debra Krol of the Heard Museum in Phoenix, which not only has Baje’s work in its permanent collection but also sells his books in its shop, praised the artist for his diverse body of work. “Baje’s illustrations are what really bring his books to life,” she says.

Though known primarily for his paintings, sculpture is an important part of Baje Whitethorne’s oeuvre. He does his casting at the Bronzesmith Fine Art Foundry and Gallery in Prescott, Arizona. “Baje came to us about 15 years ago with a carving of a Yeibichai (deity) dancer, called The Mystic One, and hired us to cast it. The entire edition of 31 sold out, which encouraged Baje to develop new pieces,” says Bronzesmith owner Ed Reilly. “His imagery rang true with me. I’ve spent a lot of time around the Navajo culture and I loved the way his watercolors portrayed the Yei dancers — they had a lot of movement. I was impressed by how he worked in three different styles: Realism, Abstraction and a combination of the two that you might call Surrealism. But what I really like best about Baje is that he respects his culture and shares it with others. He also has a reputation for mentoring young people of all backgrounds and giving back to the community,” he says.

Back in his studio on that fall morning, it occurred to me that Baje’s life is really a lesson in living. His commitment to work, to art, to family, to community is an inspiration. That much is evident in the example he sets for his son.

Toward the end of our visit, I spoke with Baje Jr., who has followed in his dad’s footsteps to become an artist. His work honors his father by continuing the family narrative tradition through a more contemporary lens. Baje Jr.’s own imagery is influenced by street art and makes dynamic references to the urban environment. His paintings point the way to the next wave of Navajo artists. As his father before him, there is no doubt that Baje Jr. will leave his mark.

- “Sunset Color Smoke” | Oil | 48 x 60 inches | 2014 WA

- “White Canyon” | Oil | 40 x 16 inches | 2015

- “Wind Dancer Black” | Oil | 18 x 24 inches | 2016

- “Sky Dancer” | Oil | 24 x 36 inches | 2015

No Comments