01 Dec Breakthrough

STANELY NATCHEZ IS IN HIS SANTA FE STUDIO, getting ready for his 2014 Indian Market opening reception, when he announces, “There are a lot of people out there who can’t afford one of my paintings… so I’m going to give them one.”

Natchez was in the process of silkscreening a stack of 9-by 12- inch canvases, in multiple colors, of the Kiowa chief Two Hatchets, that would be given as gifts to 50 lucky individuals. The plan was to give something back to the Santa Fe art community, which has allowed Natchez to live completely off the sale of his work for the last 20 years. As the largest (and most competitive) Native American art scene in the country, that’s quite an achievement.

Natchez, who’s Shoshone-Tataviam, arrived in Santa Fe during the late 1980s for a show with the legendary dealer Elaine Horwitch. It was his first exhibition after earning his undergraduate degree from University of Southern California and his master’s from Arizona State. When Natchez arrived at the gallery, he looked around and noticed the walls were hung with Warhols and Scholders. He was nervous about whether his work would hold its own with Pop and Native art royalty. He also wondered, like all newly minted art-school graduates, if he’d be able to support himself with his art. By the end of the opening reception at the gallery, he had his answer: The show sold out.

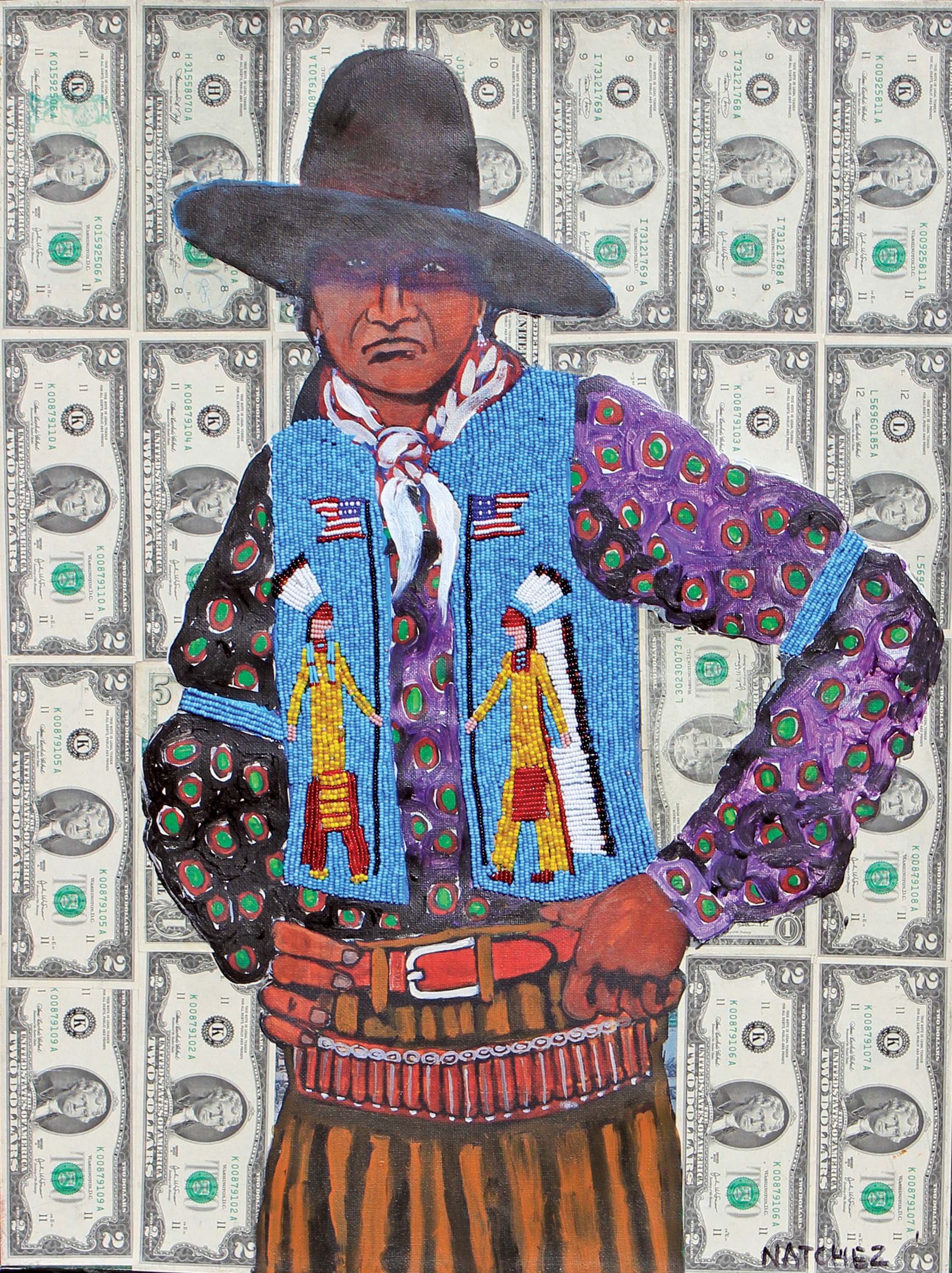

Natchez’s success can be partially attributed to his inventive use of materials. At any given time, he has included beadwork, gold leaf, maps, old pages from Harper’s and even puzzle parts. The artist’s breakthrough occurred when a friend gave him a sheet of 32 uncut dollar bills. After mounting the sheet of currency on a canvas, Natchez painted a traditional buffalo hunt scene on it. As he put it, “I knew I had found something that hadn’t been done.” The effect was electric; the artist had come up with a way to honor his forefathers, while staying current.

“We had our own style of doing art that wasn’t accepted until much later,” he recalls. “The first Indian paintings were done on buffalo hides during the 1880s to 1890s. The sheet of money is a modern-day buffalo hide. After doing my first money paintings, I bought $2,000 worth of currency from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, D.C., and began a series of images depicting Native chiefs and warriors, including Medicine Crow, Ten Bears and Two Hatchets.” The work resonated with irony as these long-ago tribal leaders confronted the likeness (on dollar bills) of the early Anglo leader George Washington. These pictures, among Natchez’s finest, were simultaneously old and new. As his friend and colleague Tony Abeyta summed it up, “Stan looks into the past, but makes images which incorporate artifacts of contemporary culture.”

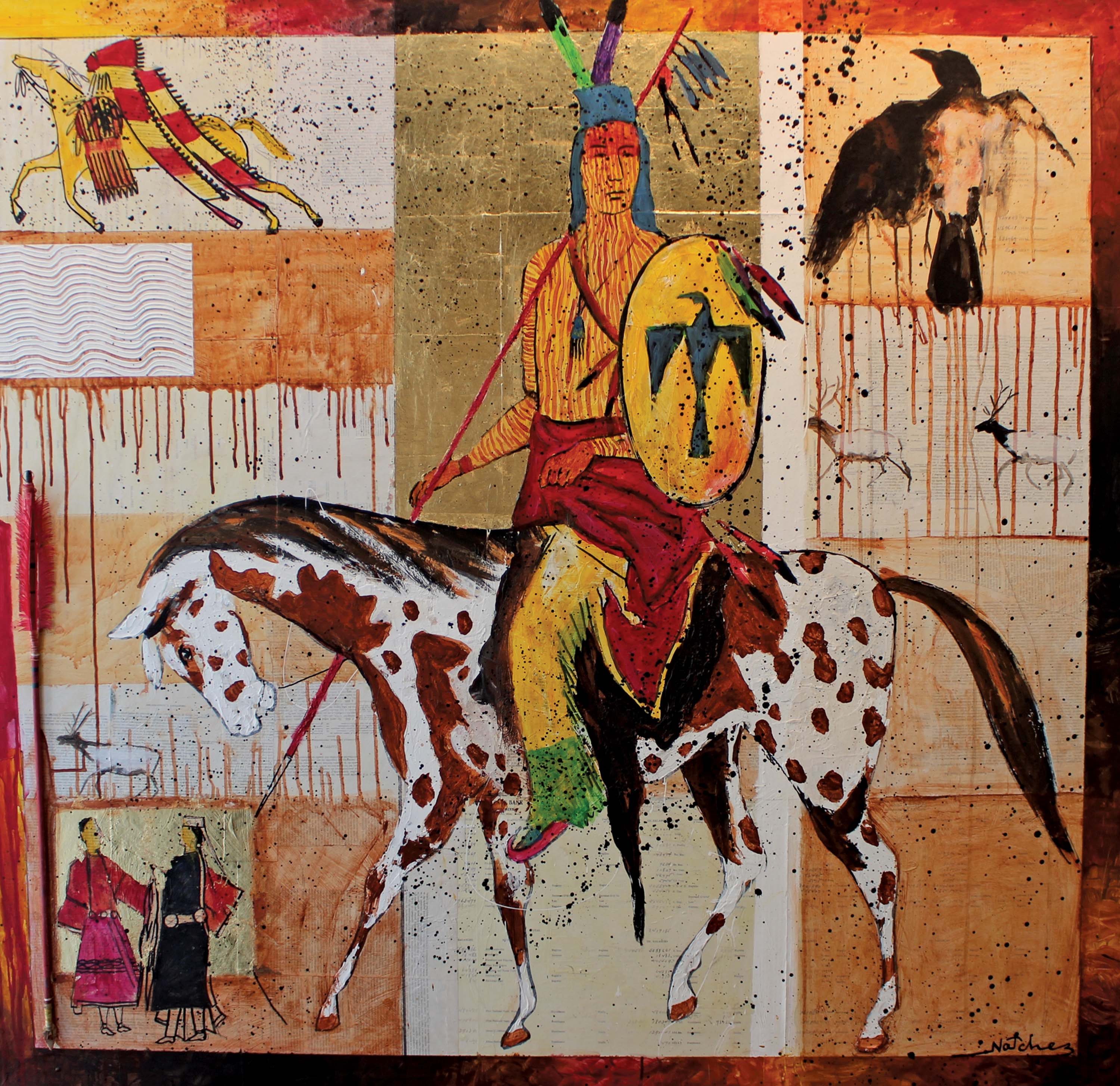

Encouraged by the results, Natchez upped the ante by overlaying “ledger” drawings on currency. During the late 19th century, when various Plains Indian tribes were incarcerated, some were given ledger accounting books along with pencils, ink and watercolors by their white captors. They drew images from memory, including battles, buffalo hunts and courting scenes. Though now collectible, these works on paper are controversial because they were done under duress while the artists were prisoners. Natchez chose to harness these strong emotions in a painting poignantly titled Capture the Flag. Here, he depicts a lone Indian on horseback carrying an American flag, while being shot at by government troops. The image is as beautiful as it is disturbing.

Before becoming a full-time artist, Natchez pursued other interests, including a stint as an editorial advisor for Native Peoples magazine. He also taught school. His most recent appointment was as the chair of the humanities department at ORME, a wealthy private school in Sedona. Though Natchez enjoyed the experience, he found himself drawn to the artistic life. He eventually found two storefronts on East Palace Avenue, just off the famous downtown Plaza in Santa Fe. One building serves as his personal gallery and the other houses his studio. The Stan Natchez Art Gallery is a handsome space that allows visitors to experience the full depth of his art. The main room is hung salon style with a diverse group of images that reveal the influence of Andy Warhol. Natchez is proud of the connection, feeling he accomplished his goal of being able to “take Warhol and do something else with it.”

But other galleries represent him as well. Among them is Modern West Fine Art in Salt Lake City, Utah. Gallery owner Diane Stewart recalls how she came to represent him: “I was visiting Santa Fe and stopped by Stan’s gallery. I met him, fell in love with the work and wound up buying several pieces from his currency series. I think this body of work is pure genius; the paintings are beautiful and compelling. They comment on the way money has changed the Indian — for better and worse.”

Peggy Lanning, owner of the Turquoise Tortoise Gallery in Sedona, Arizona, has been representing Natchez for close to seven years. “Stan Natchez has a brilliant mind,” she notes, first and foremost. “And it allows him to translate sophisticated and thought-provoking ideas onto each of his canvasses. We see his true gift as being the manner in which he blends traditional Americana imagery with traditional imagery of Native Americana; he shows us, with no shadow of a doubt, that you cannot have one without the other.”

As we talk, Natchez is willing to take on even the touchiest subjects. I ask him about Indians who rely on painting stereotypical Native American imagery. “They’re Indian artists when they need to make a sale. I’m an artist who happens to have been born an Indian. It’s an important distinction,” he explains. He’s more than happy to talk about his Shoshone-Tataviam background and his lifelong participation in tribal dances. Natchez has performed in European capitals and throughout the United States, designing his own elaborate beaded outfits, iconography that often appears in his artwork. He also credits dance as a medium for creating cultural self-esteem: “If you want knowledge of the white man’s world you get a college degree.

If you want knowledge of the Indian world you participate in ceremonies.”

It’s a Friday evening when I return to the Stan Natchez Art Gallery where the opening for his recent work was getting underway. Stan made an announcement, “We’re having a giveaway tonight and we’re just waiting for our singers to arrive so they can perform a giveaway song.”

Ten minutes later, there was still no sign of the singers. Stan said, with a smile, “They must be running on Indian time!” Finally, three young men from the Jemez Pueblo walked in. They formed a semicircle and began chanting and drumming while Stan distributed blue plastic bags, each containing a small canvas. Paintings were given to collectors, supporters and friends. Though every picture was photo-silkscreened with Two Hatchets’ likeness, no two were alike since the background colors varied. They were intentionally placed in bags so there was no favoritism shown.

Stan surveyed the scene as the singers continued to entertain. The room buzzed with delighted fans, thrilled to add a new Natchez to their collections. They approached the artist to thank him for his act of generosity. It was obvious that he savored the interaction. Then I overheard him say to someone, “My art is about you and the way I respond to you. That is my experience.”

- “Capture the Flag” | 24 x 36 inches

- “Clan Mothers” | Oil and Mixed Media on Goldleaf | 30 x 40 inches

- “21st Century Dandy” | 40 x 30 inches

- “Medicine Crow” | 52 x 80 inches

- “War Horse” | Mixed Media | 54 x 52 inches

No Comments