30 May Casa de Vidrio

UP A WINDING ROAD, ON A RIDGE JUST OUTSIDE OF SANTA FE, LIES CASA DE VIDRIO, a Pueblo-style sun salutation silhouetted against a brilliant New Mexico sky. The residence of Richard and Betsy Ehrenberg is the culmination of a dream — a dream the couple shared of a perfect backdrop for their world-class studio art glass collection. Their home would be a place where, as Betsy says, “Something beautiful can be seen from anywhere in the house.”

The Ehrenbergs, in collaboration with Santa Fe-based architect Aaron Bohrer, have created a stunning marriage of architecture and art. Bohrer has honored the couple’s affection (and his own) for the Native American Anasazi culture in elements sprinkled throughout the sprawling 5,600 square-foot residence and the 1,600 square-foot guest house. For example, the circle, a symbol of unity or infinity — a constant in the art and architecture of the Anasazi — is also a recurring design theme in everything from the overall concentric circular design of the home to its curved hallways, ceiling and wall cutouts. The Ehrenbergs have taken this symbol for their own in a home that honors the land and human creativity with a prevailing sense of continuity and caretaking.

Aaron Bohrer is a self-proclaimed “architectural archaeologist” who favors modern reiterations of tradition for their connection to and continuation of New Mexico’s past. Casa de Vidrio reflects the style of the sacred Great Kiva of Pueblo Bonito ruins at Chaco Canyon, discovered deep within the remote deserts of northwestern New Mexico. The kiva’s structural interplay of squares and circles is striking, as is its orientation to allow views of summer and winter solstices, sunrises and sunsets. Kivas represent an apogee of Anasazi culture and architectural skill and the Ehrenberg home is a modern gesture toward this ancient tradition.

The Ehrenbergs wanted to make the most of the 360-degree views from their 14-acre site near the Santa Fe Opera, yet they had to adhere to stringent land-use restrictions. It was a priority that the buildings respond to the views, the climate and the aesthetic of the landscape, to blend in with the surroundings. They succeeded admirably. Although their home appears contemporary in every carefully crafted detail, it has a natural and historic sensibility, inviting light and landscape indoors, blending the two.

Arriving visitors pull into a covered circular auto court delineated by a curved stone wall replete with periodic portal views of the Sangre de Cristo mountains. Between the stone wall and the house is a narrow exterior garden that leads to the traditional key-shaped “Anasazi” entrance. Just beyond the entry is a round skylight, which in summer months casts a brilliant solar disk on the ground and walls surrounding the narrow garden. A massive, custom glass front door acts as a translucent membrane between the outdoor and indoor environments.

An interstitial, the foyer is designed to reference a traditional New Mexican church, with high, clerestory windows dropping direct, natural light into the space. Surrounded by art, the eyes are immediately drawn to a spectacular, one-of-a-kind, carved and painted sculpture standing chest high in front of a freestanding panel of three 8-foot-tall windows that divide the foyer and the living room. Double Clear Handout/Handsoff, a collaboration between Judy Chicago and Santa Fe artists Norm and Ruth Dobbins, was born out of a study Chicago began of hands and gestures in 2004. After two years of learning about glass properties, inventing carving and etching techniques with Norm and Ruth, the piece was unveiled at the LewAllen Contemporary gallery in Santa Fe and instantly snapped up by the Ehrenbergs.

Featuring a dramatic, convex exterior wall of 9-foot-by-8-foot solid glass panels, the living room is designed to extend into the sweeping portal immediately adjacent. The size of each glass panel consciously replicates the open space between each column of the portal, creating a rhythm of glass, column and space. The effect is one of continuous flow, an effect that becomes reality when the glass doors are pocketed into a wall, merging interior and exterior, and framing the near and distant views of mountains, valleys, villages and the spare foliage of the northwestern New Mexico landscape. Casa de Vidrio easily accommodates 100 guests for events, with an additional 100 seats for concerts on the covered portal.

Natural light pours into the living room and is captured by glass works in nichos, on shelves and in life-size sculptures. A gorgeous botanical piece by Robert Mickelsen, an artist known for his flame-working expertise and amazing artistic interpretations, holds a place of honor in a center nicho. Near the windows, Spooner Marcus and Ira Lujan’s Red Totem forges a bold shape against the view, and, on the piano, sits an intricate footed platter by Peter Houk.

To avoid any sense of clutter, Casa de Vidrio contains 31 nichos designed to showcase pieces of the Ehrenbergs’ glass collection on an ever-rotating basis. Each nicho is custom designed, with a bottom shelf constructed of laminated Starfire™ frosted glass that diffuses halogen light evenly onto the art from below. The effect is to illuminate every facet, every skillfully crafted element of each piece. Throughout the house great attention to detail and ambiance has created, as Bohrer describes it, “a distillation of basic natural phenomena of sound, light and air into a dwelling with objets d’art that are themselves creations of light and color.”

The Ehrenberg’s romance with studio glass art began when they inherited an antique paperweight collection from Richard’s father, Raymond Ehrenberg, who started his collection in the 1920s. In that era, the finest paperweight makers were Baccarat, Clichy and Saint Louis — and through the years Raymond collected them all, some dating back to 1847. Richard and Betsy wanted to add contemporary weights to the mix, and soon fell under the spell of the world of glass art. In the galleries they visited, “contemporary studio glass art was also sold,” relates Betsy. It was only a small step to expand to other work in the medium: “When we saw larger sculptures, dramatic interpretations, meaningful art in glass, well, it was an easy path to follow.”

Richard and Betsy visited the famous Pilchuk school in Stanwood, Washington, and soon were immersed in learning everything they could about this difficult, demanding medium. They wanted to support emerging artists and, as with many collectors, to know them and the stories behind their art. “We would meet with an artist and ask what his or her favorite piece was and why. We opened a dialogue, learned about them and their passion, and we felt more connected to the work.”

What began as a base of about 50 paperweights, now displayed on a rotating basis in a custom glass-topped table in the living room, grew rapidly until, today, their collection — in addition to the paperweights — comprises at least 150 pieces of studio glass art displayed throughout the main residence and guest house, with some in storage. Their interests in art are not restricted to glass. They also include the work of many other fine artists in their home, such as bronze sculptures by Nora Naranjo and John Suarez; paintings by Dan Christianson, Judy Tuwaletstiwa, Gus Heinze and Curtis Ripley; fiber arts by Olga de Amaral and Norma Minkowitz; and ceramics by Louis Marak, Martin Harpendahl and Mitsuo Shoji.

Outside the living room, to the side, a custom-glass bridge spans a curved, crushed-glass arroyo leading to the private master suite. Landscape architect Edith Katz has surrounded the house with xeriscape, native shrubs and plants, and vast expanses of wildflowers, all in keeping with New Mexico’s indigenous terrain.

Casa de Vidrio’s dining room features a Roger Atkins table of heavy, African mahogany, slightly curved on each long side, with chairs by Dakota Jackson. Centered above the table, a large ceiling nicho frames Nova, a sparkling piece by Anna Skibska, absolutely breathtaking with its bullseye-flameworked glass center surrounded by an explosion of clear orange and red glass extensions. There is no light in the piece, made over a Bunsen burner with a pair of tweezers, but when the lights are on in the room — or at certain times of the day — the piece casts a magical network of shadows over the entire room, ceiling and walls.

Moving from the dining room down a curved hallway to the breakfast room and kitchen, color is key. Fifteen hues have been used throughout the house and you can see three from any spot; as day passes into evening their tones shift with the changing light. In two of the breakfast room nichos, Latchezar Boyadjiev’s Journey and Torso feature prominently, overhead hangs a delightfully whimsical chandelier crafted of automobile fuses by Christopher Moulder, and out the windows can be seen the aspen grove, ski trails and rolling mountains, sunrise and moonrise. The fully equipped gourmet kitchen’s focal point is its Duane Dahl custom-glass countertop designed to mimic a river’s flow, embedded with Rio Grande rocks and aluminum- and copper-leaf elements, including “fish” swimming to and fro. “Betsy and Richard were incredibly fun to work with,” says Dahl, “They know and understand the glass art process so well, and gave me a lot of leeway once they had selected their water motif.”

Betsy proposes that studio art glass is “the only medium with reflection, refraction and shadows.” The value she places on community and team work is part of what inspired her to found Glass Alliance – New Mexico: “One of the things I love about glass is that you can’t do it by yourself. It is essentially collaborative, always a team effort.”

The New Mexico Glass Alliance’s mission is to create venues where the public, collectors, artists and students of contemporary art glass can gather and learn about the exceptional process and unique beauty of glass as a medium. Many members’ pieces are in the Ehrenberg collection, including, a favorite, Cia Friedrich’s Black Bird. Cia has spent extensive time in New Mexico and the northwest United States and is fascinated by the differences between the art made by Southwest and Northwest Native Americans. This sculpted blackbird brings reflective qualities to the Kwakiutl art of the Northwest. With the glass melting at 2,200 degrees, Cia used long metal tweezers (jacks) to elongate the nose and heavy-duty scissors to shape the crown. The wispy hair is actually glass beads from an antique piano scarf. Falling in love with it at first sight, Betsy acted quickly — “You snooze, you lose,” she quips.

No home, no matter how beautiful, runs smoothly unless underpinned by a fine-tuned mechanical system, and Richard Ehrenberg, a retired mechanical engineer, designed and oversaw this entire process for Casa de Vidrio. A series of remote thermostats, with sensors buried in the walls to avoid unsightly aesthetics, are wired to a series of digital controls in the equipment room. There is a single system for heating both the hot water and the radiant floor. A highly evolved solar system comprised of a series of sealed, evacuated glass cylinders, with a non-reflective black finish and pipe inside each that allows liquid to boil at a higher temperature than water and transmits the heat created by conduction to the manifold pipes at the top of the collectors. Each tube may be replaced individually or the system can easily be expanded. Presently, the only energy from fossil fuels in the house from May to late September is for cooking. All domestic hot water, space heating and spa are completely supplied by the solar system and meet an estimated 30 percent of their total energy requirements.

Betsy Ehrenberg, whose interest and education in computer science and mathematics provided the technical background for her early stints at IBM and Hewlett-Packard, went on to start her own software consulting firm. She is a serial entrepreneur who continues to rack up outstanding achievements in the commercial and nonprofit worlds. The talents and energy that are the bedrock of her career carry over abundantly to personal pursuits. In addition to Glass Alliance – New Mexico, Betsy founded “Bridges to Santa Fe,” which designs and implements a variety of art events, tours, seminars and conferences, and provides transitional services for organizations considering relocation to Santa Fe.

Leaving Casa de Vidrio, winding back down the hill with the long afternoon shadows behind them, visitors are often reluctant to leave this special house of glass, this house of stories, with “something beautiful to see” in every corner of every room. Richard and Betsy Ehrenberg dreamed of a home with a profound connection to creativity, unity and the natural world. The dream has come true.

- Native Flowers Bouquet Orb, by world-renown glass artist Paul Stankard.

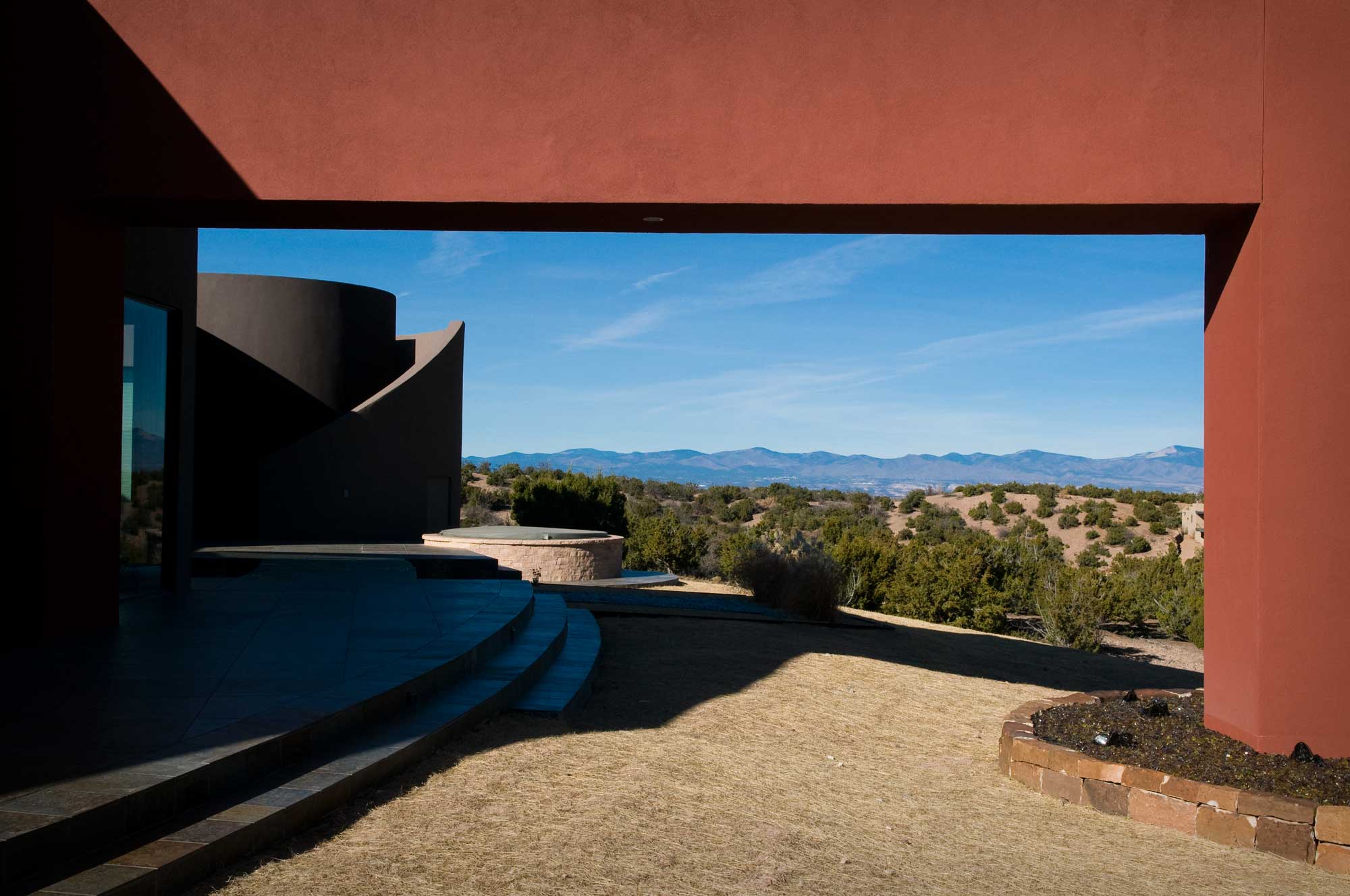

- Architect Aaron Bohrer’s exterior design incorporates a striking terra-cotta red linear wall running perpendicular to a circular “acequia of light,” providing a dramatic frame for surrounding views

- Auto court to “Anasazi” entrance.

- Living room views through convex glass-paneled exterior wall to portal and beyond. Cast glass Spirit Boat by Mark Abildgaard.

- Curved hallway leading from dining areas to main foyer features glass art nichos throughout.

- Living room, custom columnar nichos, and, in the foreground, Shaded Pool, ceramic by Louis Marak.

- Duane Dahl’s custom-glass countertop reflects a river’s flow and creates a stunning focal point for the kitchen.

- Intricate slate and bamboo flooring patterns create design interest as the convex hallway flows away from the main living areas. Opening to the left is the breakfast room, showing a glimpse of Christopher Moulder’s Schprokets, a glittering automobile-fuse chandelier, and, on the wall, Olga De Amaral’s gold and white tapestry Stone White I.

- Cia Friedrich’s sculpted-glass Black Bird in front of Curtis Ripley’s mixed media Hero.

No Comments