29 Dec Chief. Shadow Catcher. Sign Talker.

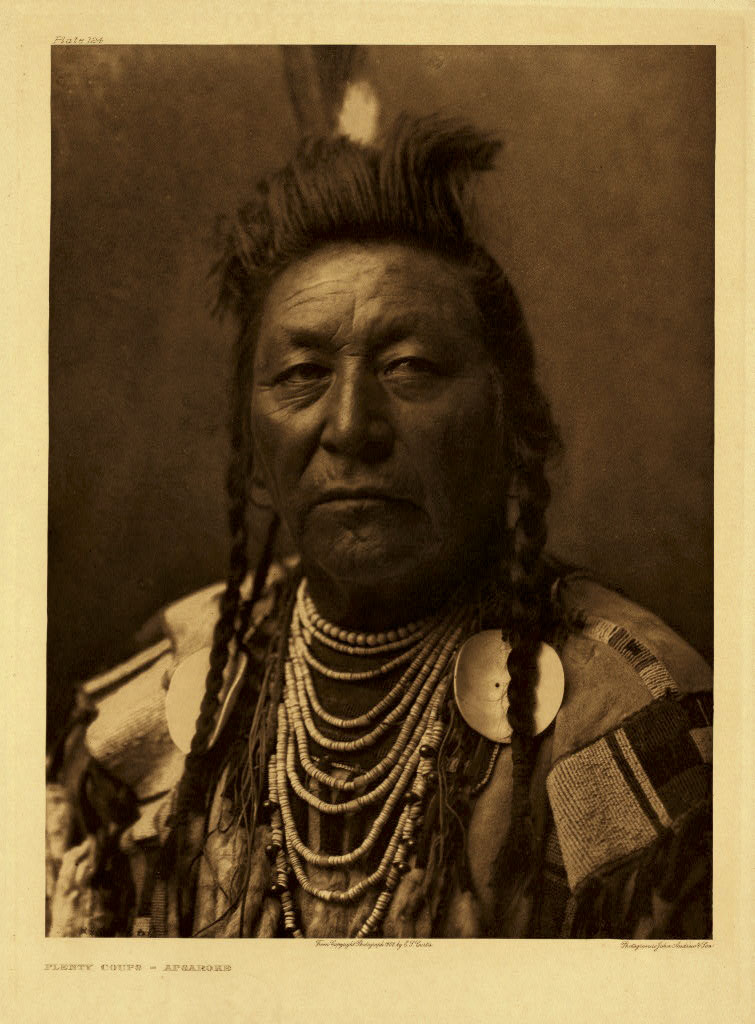

I'D LIKE TO THINK I HAVE SOMETHING IN COMMON WITH THEM — Chief Plenty Coups, Edward Curtis, Frank Linderman — and with the person who gave me their legacy. Four of us are transplants from the Midwest. The Chief, however, was not. He lived and died on the land where he grew up, near Red Lodge, Montana; his lodge today, a state park in the noble land of the Crow. This portrait hangs, not by accident I believe, in my living room, reminding me of this great warrior, prophet and peacemaker’s message: You don’t have to fight to win.

I came upon this non-accident on an autumn day in my first of 13 years in the Flathead Valley, homesick for a little urban art fix. When you’ve been lucky enough to feast on the Renaissance for a year in Florence, to work in the Prints and Drawings Department of the Art Institute of Chicago and actually hang out with stuff like Monet’s sketchbook and boxes of Rembrandt etchings, it’s hard not to crave excellent art, even in the natural palette and vernacular of the Rockies.

I struggled with this my first few years as a Montanan; how to look up for inspiration, and not for the footholds of what humankind has done, which, until very recently was usually more of a bane to the natural world than an inspired reflection of it.

In short, I pulled up to an old red barn with a small sign that read AUNT TEEK’S. This was not sunny Vermont with discerning couples in tweed eyeing Staffordshire dogs for cracks. There were no Antiques Roadshow types ogling majolica oyster plates or cloisonné horse bookends. As is much of Montana, this place was dead empty. And standing amongst old branding irons, wagon wheels and rusty milk urns I got that sinking feeling I so often got in those days — you don’t belong here. That’s when I saw the Chief.

He was leaning against a stack of other framed images along the floor. I went to him with my mouth open. I had been a fixture at the Edward Curtis gallery in Seattle for years, sifting through the collection in hopes of acquiring just one photogravure. On layaway. On a writer’s salary. But different winds had taken me to Montana, and there I stood, holding not only what I was sure was an Edward Curtis, but a big one, and a portrait, nonetheless, in a painfully acid-rich looking mat.

“You know what that is. Don’t you?” said a voice behind me, and I turned to see a yellowed, dried man; as if he’d been living in the same acidic frame for too long.

“Edward Curtis, yes?”

He nodded. “But do you know which Edward Curtis?”

“No. He’s so … proud.”

He went to a case and pulled out an old book; said, “I’d like to show you something,” tears pooling in his eyes.

In a city, I wouldn’t have followed him, in this equivalent of an empty warehouse where screams for help would not be heard. But here I did follow; this was part of the beauty of Montana, wasn’t it? Freedom — safety — answering the call of simple human connection.

With the Curtis under his arm, he led me to a small office and offered me a seat across from his desk where he held the book like a hymnal. “I’m dying,” he said. “I won’t see the aspens turn. Because you know that this is a Curtis, I’d like to tell you a story.”

“I’m a writer,” I said. I hadn’t said those words yet in Montana. “I live for stories.”

He smiled through a pained face and said, “This is Chief Plenty Coups of the Crow. As a young boy, he had a dream. In it, the earth opened and swallowed the buffalo. Then from the same hole came the spotted buffalo, the cow, covering the land. Then a great wind came and blew through the forests. A tiny chickadee took refuge in a hollow tree, weathering, surviving, the storm.”

He ran his hand over the glass covering the Chief’s face. “This was Plenty Coups’ gift to his people. ‘Work with the white man — don’t fight. And we will keep our land.’ And they did.”

Then he told me about Curtis and Linderman.

Four years of art history classes and I’d never seen passion like this. Called Shadow Catcher by some tribes, in the early 20th century photographer Edward Curtis took 40,000 images of more than 80 American Indian tribal groups, ranging from the Inuit of the far North to the Hopi of the Southwest. Largely viewed as a vanishing race, it was Curtis’ dream to capture these native people in their traditional settings and regalia, with dignity and respect at the core of his mission.

Similarly, Frank Linderman (born in 1869) devoted much of his life to Montana’s Native Americans, learning and writing about their ways, and gaining their trust so that he could document stories that would otherwise be left untold. He was adopted into three tribes: the Blackfoot, the Cree and the Crow.

The man (whose name I never learned) opened Linderman’s book called American and held it up. “This is the thumbprint of Plenty Coups,” he said. And then he read the quote above it:

I am glad I have told you these things, Sign-Talker. You have felt my heart, and I have felt yours. I know you will tell only what I have said, that your writing will be straight like your tongue, and I sign your paper with my thumb so that your people and mine will know I told you the things you have written down.

He drilled his milky eyes into mine and said, “I will give you the Plenty Coups, and this first edition American if you promise to share the story. ‘You don’t have to fight to win.’ ”

Years later, when I built my house, I designed a special place for the Chief, so that he might hold vigil over our little family and our land. I tell this story whenever it seems to want wings. And I pass it to you, that you might also.

Postscript:

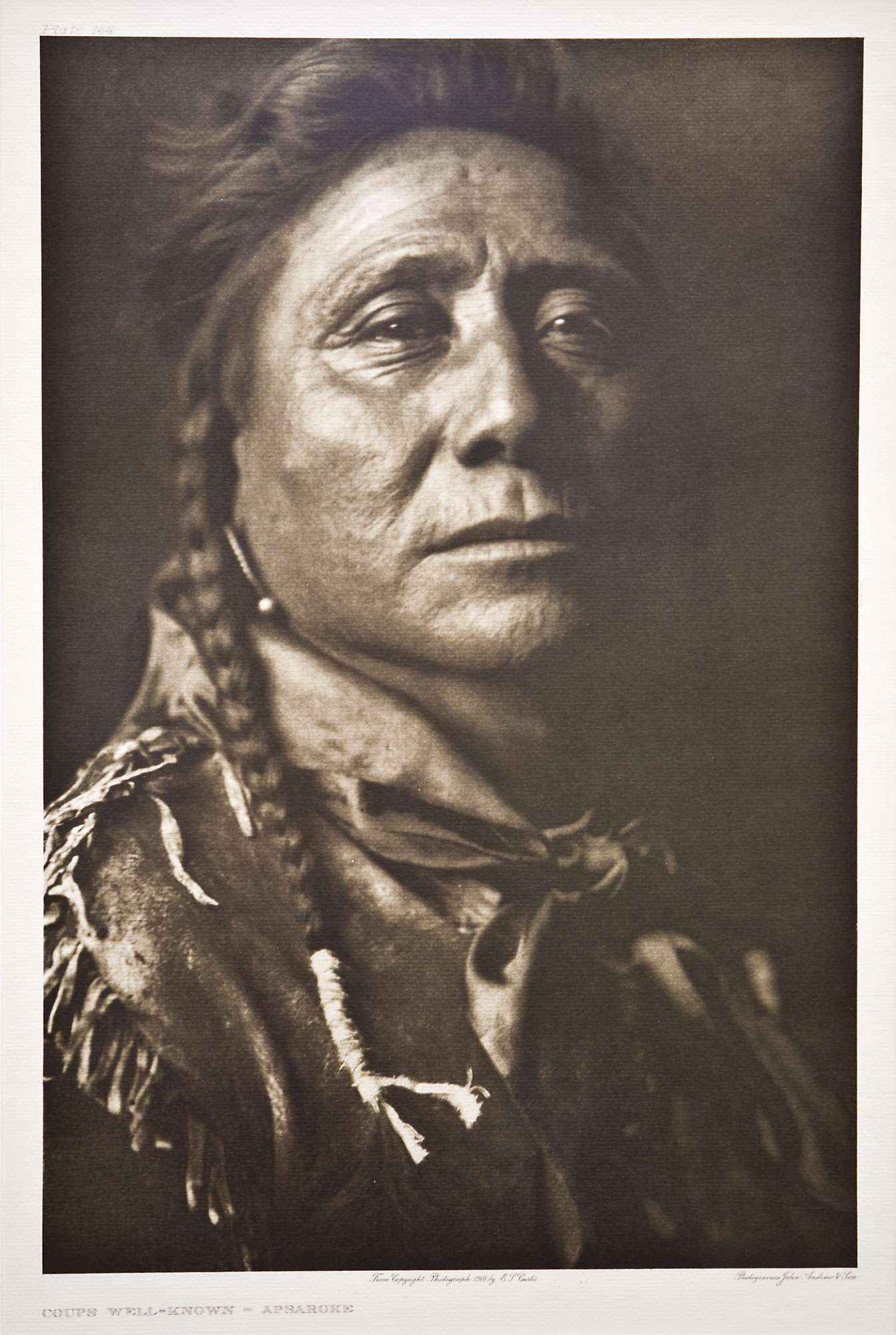

Recently, I learned that it is another Curtis Crow photogravure that hangs on my living room wall — not the Chief after all, but rather the image of Coup Well-Known. His eyes tell me he knows his chief’s message well. And through them, I see even more evidence of Plenty Coups’ rich legacy.

Heath Korvola works worldwide as a location photographer for commercial and editorial clients covering active lifestyle and modern living. He lives in the northern Rockies in the ski town of Whitefish, Montana.

- “Plenty Coups — Apsaroke”, Edward S. Curtis, 1909, photogravure. Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s ‘The North American Indian’: the Photographic Images, 2001.

No Comments