30 May Cowgirls & Indians

THE GILCREASE MUSEUM, founded by oilman Thomas Gilcrease in 1949 and set on 460 scenic acres just northwest of Tulsa, Oklahoma, is caretaker to one of the finest collections of Western art and artifacts in the world. Its more than 300,000 paintings, artworks, artifacts, journals, books, documents and maps detail the arc of natural and human history in the American West. From Remington to Bierstadt, from Catlin to Bodmer, and including entire collections of works by such luminaries as Thomas Moran, Alfred Jacob Miller, Charles Russell and the Taos Colony artists, virtually every significant artist who has captured the West’s monumental spaces, historic events and charismatic people is represented here.

To say, then, that Wyoming portraitist Carrie Ballantyne was honored to be selected by the museum as a featured artist for its 2010 Rendezvous would be an understatement. “The Gilcrease Museum has the finest Western art collection in the world. It’s just phenomenal,” says Ballantyne. “It’s such an incredible honor that they would even consider me at this very prestigious museum.”

Ballantyne’s drawings and paintings will be paired with sculptures by John Coleman, an acknowledged master bronze artist who brings an unbridled passion for American history and an acute understanding of the human spirit to bear in each of his works. An established figure in both the National Sculpture Society and Cowboy Artists of America, the Arizona resident has been honored with a long list of prestigious awards, commendations and shows. Together, the two artists represent the historic West and the contemporary West, the rancher West and the Native American West, the West rendered flat and the West rendered three-dimensionally.

Inaugurated in 1980, the Gilcrease Rendezvous followed the same format for years: one painter, one sculptor, showing together. The exhibit was both a career-spanning retrospective and a look at the artists’ new work. In 2004, Rendezvous celebrated its 25th anniversary by inviting every artist who had participated previously. Although a very successful event, this year the show reverts to its original structure.

Explains Dr. Duane King, executive director of the Gilcrease Museum, “We want the Rendezvous show to call attention to some outstanding artists. It’s a very special honor for the artists selected. Carrie Ballantyne and John Coleman are superb artists at the top of their field; they have a lot of output and have perfected their skills, so they really are masters of their profession. They’re both at the point in their careers where they deserve this recognition. Our intent with the retrospective is to honor them and give them the recognition when they still have time to benefit from it.”

While Carrie Ballantyne works flat and depicts contemporary Western characters, mostly ranch women, John Coleman works three-dimensionally, frequently drawing on historical events and characters to portray strong individuals at a specific moment in time whose actions and demeanor symbolize a larger truth about the human condition in a changing world.

Ballantyne and Coleman, despite their obvious differences — in media, subject matter and their own Western lifestyles — have many career similarities. Strikingly, both made bold changes when already established in their careers. At 42, Coleman walked away from a successful business as soon as he could responsibly do so in order to be a full-time artist; he’s never looked back. Ballantyne was a hugely sought-after pencil artist for years when she removed herself from the art market for two years in order to become an oil painter. Both artists followed their hearts and met with almost immediate success. A year after debuting her paintings, Ballantyne was awarded the Great American Cowboy Award at the Prix de West. Coleman, after a couple years’ study, also met with a chorus of accolades and sold-out shows. Within five years of sculpting full-time he was made a member of the National Sculpture Society; two years later he joined the hallowed ranks of the Cowboy Artists of America.

For the first 10 years of her artistic career, Carrie Ballantyne worked strictly in graphite pencils; for the next 15 years she worked strictly in colored pencils. Now she’s a painter who also does charcoal and conte drawings. The show will span her whole career, from early graphite works to new oil paintings. Throughout her career, her style has been photo-realistic, her subjects startlingly vivid and authentic due to her meticulously precise portrayals. For 30 years, she observes, “My subject matter hasn’t changed. It’s still the same. It’s the local Western community of people, old and young, cowboys and Indians.”

“What’s different about me is this,” Ballantyne continues. “I learned that it’s important to me that I know the subject. I rarely will approach a person if I don’t know them. We’re a small community, so if I see someone, say, at King’s Ropes, I might ask about them. But 99 percent of my subject matter are family, friends, neighbors. They’re all people I have a relationship with. If I’m going to spend a lot of time looking at their faces I have to feel good about the person. They’re more than just models. There’s generally something in their character that I want to show the world.

“The bottom line for me is passion,” she explains. “Without passion, there’s not going to be any power to stir the heart of the viewer. I let my passion lead, but I have to look for continual support from the artistic principles of balance, in shapes, light and color. But there has to be something about the individual to excite something in me, because then the whole endeavor is about representing the thing in that person.”

John Coleman is also moved by emotion, even when rendering historic moments involving people he’s never met. But his starting point is historical accuracy. “I research everything, right down to the last detail,” he says. “It’s a lot like making a historic documentary. It’s important to me that I respect my subject. I don’t start anything until I know what I’m doing. “

Because his details are so precise and so true, viewers might focus on the vividness and accuracy of his portrayals: the eagle feathers on an old warrior’s headdress, the textural rendering of folds in a worn deerskin garment, the bells on the belt of a child dancer. But a look at the subject’s hands, or the set of the shoulders, or the lines on the face, or a wistfulness in the eyes reveals that the feeling — and thus the true meaning of each piece — comes from the artist’s deliberate conveyance of mood.

“Art is a form of communication,” Coleman points out. “I’m identified with Indian subject matter, but I think more in terms of the metaphor. I use historic events to describe something else. Whether it’s a bucking horse or the Lincoln Memorial, it’s about what kind of mood is created in the piece. I’ve always really enjoyed mythology; I like metaphors. I’m creating symbolism in some form, to convey a universal history.”

Both artists draw fully on their artistic excellence and depth of feeling to depict the West that inspires them. Says Ballantyne, “The passion creates the mood and the emotion, and that’s what draws the viewer in. Without the passion,” she says, “there’s no emotion to stir the heart.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Portrait artist Carrie Ballantyne and sculptor John Coleman will each have 8 to 10 pieces of art available for purchase at the Gilcrease Rendezvous. The retrospective exhibition will feature work that spans the artists’ careers. The Evening with the Artists and Art Sale is Friday, April 16. Ballantyne and Coleman will both present talks that day. Rendezvous opens to the public on April 17 and continues through July 11, 2010.

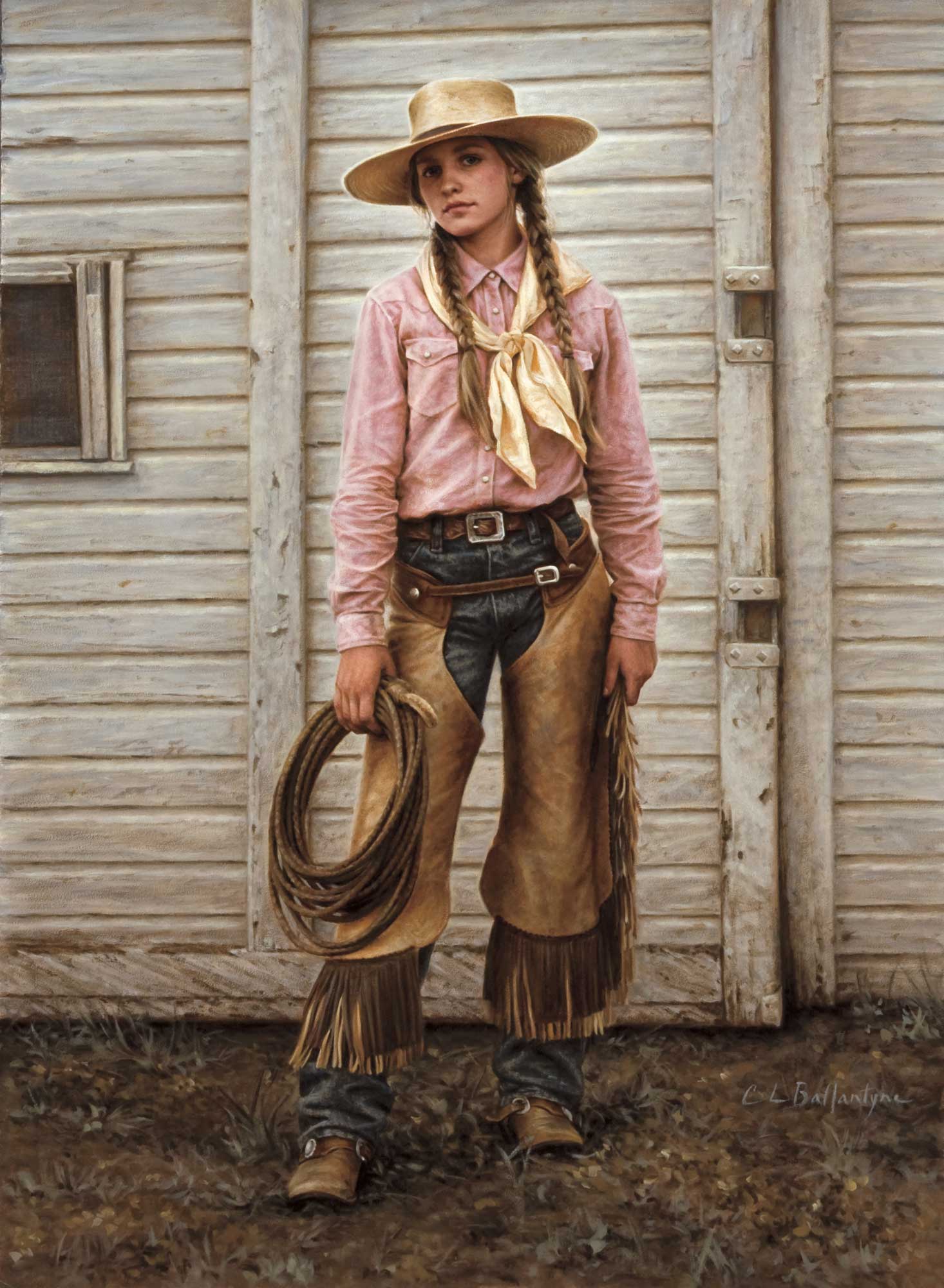

- Carrie Ballantyne

- John Coleman, “Kokopelli”, Bronze, edition of 50, 11 x 8 x 12 inches

- Carrie Ballantyne, “Reata”, Oil, 20 x 14.5 inches

- Carrie Ballantyne, “Grandpa’s Girl” | Oil, 16 x 12 inches

- John Coleman, “Winds of Change”, Bronze, edition of 35, 25 x 7 x 7 inches

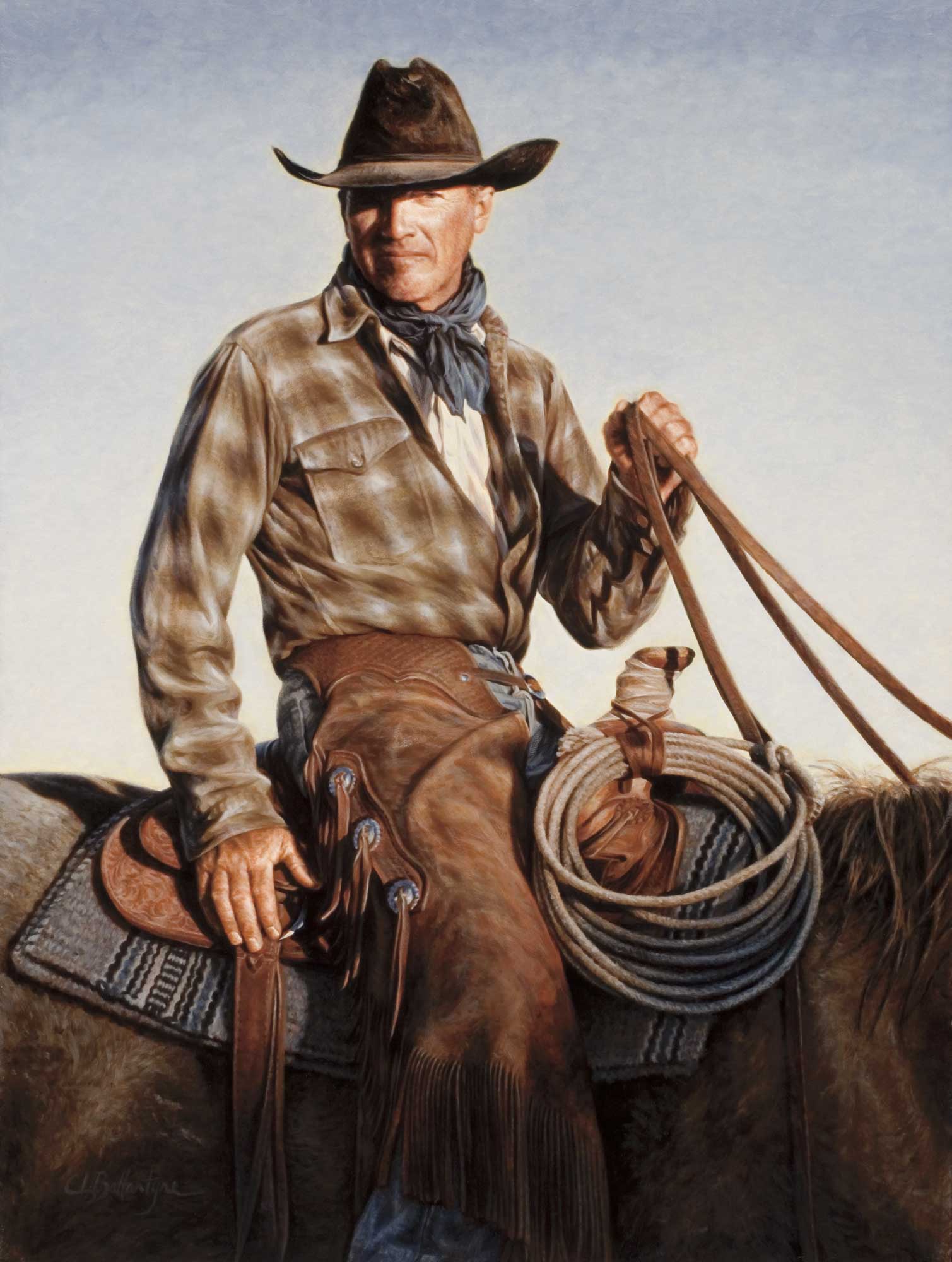

- John Coleman

- Carrie Ballantyne, “A Montana Man”, Oil, 24 x 18 inches

- Carrie Ballantyne, “Sweet Innocence”, Conte/Charcoal, 11 x 9.5 inches

No Comments