05 May Creating Context

An ongoing exhibition at the Tacoma Art Museum (TAM), On Native Land: Landscapes from the Haub Family Collection, seeks to reorient our perception of Western art. The exhibition situates landscape paintings from the Haub collection in the context of the more than 75 Native American communities whose homelands are pictured in the artwork.

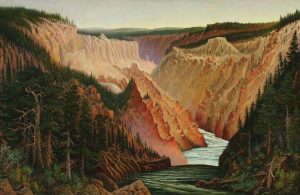

Grafton Tyler Brown, A Canyon River with Pines and Figures (Yellowstone) | Oil on Canvas | 35.75 x 56 inches | ca. 1886 | Courtesy of Tacoma Art Museum. Museum purchase with funds from the Art Acquisition Fund and the Tacoma Pierce County Black Collective

The vast majority of Western art depicts landscapes and wild animals devoid of human presence, idealizing a natural environment that exists separate from and without people. Yet, virtually all of the American West was, and remains, populated by Indigenous peoples who have — according to the latest anthropological evidence — been here for at least 20,000 years. On Native Land aims to reveal how the erasure of Indigenous history happens in subtle and unconscious ways. As Faith Brower, Haub curator of Western American art at TAM, explains, “Addressing what was neglected in these paintings is part of a meaningful conversation happening right now.”

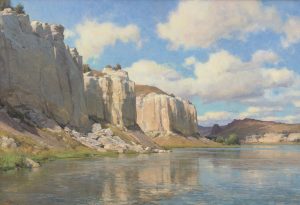

John Mix Stanley, Scene on the Columbia River | Oil on Canvas | 17.125 x 21.125 inches | 1852 | Courtesy of Tacoma Art Museum, Haub Family Collection. Gift of Erivan and Helga Haub

Each of the 14 landscapes in On Native Land includes a land acknowledgment that appears on a label next to the artwork. In this way, the exhibition hopes to expand the scope of how we interpret landscape paintings, especially in the West, where many Native American communities continue to flourish on ancestral lands. “We invite visitors to learn and share with us about land ownership, treaty rights, reservations, and Indigenous place names while considering the history of the land,” says Brower. “By connecting with members of the tribes whose homelands are depicted in On Native Land, my hope is to learn more about how these places remain vital and meaningful to Native American communities today.”

Thomas Moran, Green River, Wyoming | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 28.25 inches | 1907 | Courtesy of Tacoma Art Museum, Haub Family Collection. Gift of Erivan and Helga Haub

Brower points out that at TAM, “we have been reciting land acknowledgments at programs for a number of years.” The museum is located on the homelands of the Puyallup Tribe, and the museum recently updated its land acknowledgment, consulting with members of the tribe to do so. Brower began thinking more deeply about the whole concept of land acknowledgments in the context of the artworks themselves. She says she started to understand “how these sentiments could take on additional meanings outside of plaques on the façade of a building and salutations at events. I hope that by providing written land acknowledgments alongside landscape paintings, we can offer recognition to the many different communities who have deep and meaningful connections to the places pictured.”

Curt Walters, Supreme Moment of Evening | Oil on Canvas | 40 x 60 inches | 1993 | Courtesy of Tacoma Art Museum, Haub Family Collection. Gift of Erivan and Helga Haub

To this end, the exhibition presents various perspectives about the subject of land acknowledgments through resources available in the gallery and online, including articles and videos. Quick Response (QR) codes are located throughout the exhibit so that with a quick scan, visitors can engage with Native American voices associated with the specific regions depicted in the artworks.

“On Native Land offers visitors an opportunity to explore landscape paintings while recognizing the important cultural history of the land,” says David F. Setford, executive director at TAM. “This exhibition continues efforts at the museum to think broadly about the ways in which artworks are interpreted and how TAM can better work with communities to share important stories.”

Brower has worked with the Haub Family Collection for roughly five years and began research for this exhibition in 2021. From the Haub Collection, she selected 14 artworks by well-known artists that depicted familiar locations so that the museum could provide precise information about the area’s cultural history. She emphasized works in which the environment was the primary subject, revealing little evidence of human impact. The show also pairs historical paintings with contemporary ones, Brower says, “in a range of artistic styles in order to demonstrate how this curatorial strategy is applicable to a range of artwork.” She also worked closely with Puyallup ribal members Charlotte Basch, whose curatorial work involving landscape paintings and honoring Indigenous communities laid the groundwork for the exhibition, and Amber Hayward.

Clyde Aspevig, White Cliffs of the Missouri | Oil on Board | 40 x 60 inches | 2009 | Courtesy of Tacoma Art Museum, Haub Family Collection. Gift of Erivan and Helga Haub

One of the pieces in the exhibition is A Canyon River with Pines and Figures (Yellowstone), painted in 1886 by Grafton Tyler Brown [1841–1918]. The work depicts a formidable stretch of river coursing through a rugged canyon in the nation’s first national park. The piece is coupled with a 3-minute NPR broadcast documenting a declaration made by the Piikani Nation in Alberta, Canada, of their opposition to modern place names in national parks, especially those that commemorate anti-Native figures from the past, such as Army Lieutenant Gustavus Doane, who helped massacre more than 200 Blackfeet, mostly women and children in Montana. Mount Doane in Glacier National Park is named for this nefarious figure, and the Piikani would like to see the name changed.

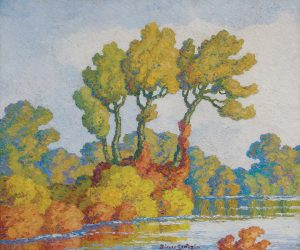

Birger Sandzén, Autumn (Smoky Hill River, Kansas) | Oil on Canvas Mounted on Panel | 20 x 24 inches | 1944 | Courtesy of Tacoma Art Museum, Haub Family Collection. Gift of Erivan and Helga Haub

Brower is enthusiastic about this innovative approach to contextualizing Western landscapes. “I hope this exhibition will impact curators, art historians, and scholars to consider adapting or modifying this curatorial strategy regarding the interpretation of landscape paintings,” she says. “I am not aware of any similar undertakings by a curator or museum, although I would be thrilled to see more of this work being done.”

No Comments