12 Sep Crossing Over

ALMOST A QUARTER CENTURY AGO, well into middle age and just shy of his 44th year, John Coleman shucked aside real estate development and, as a veritable unknown, ventured into the world of Western art. Not long afterward, something extraordinary happened: Coleman became a phenomenon. Like a comet suddenly streaking across the horizon, his emergence — most notably, his sophisticated sculptures of Native American subjects — left collectors and fellow artisans stunned.

Painter Bill Anton remembers thinking, “Who is this guy?”

“I had never seen anything like it, never saw anyone arrive on the scene from out of nowhere and then go to the top so fast,” Anton says, noting that equally as impressive, Coleman proved he wasn’t a short-term wonder. He’s won major awards from jurors and peers and earned national acclaim for his realistic figures, especially a series of bronzes inspired by the historic aquatints and oils of frontier painters Karl Bodmer and George Catlin.

In the last decade, Coleman’s presence has grown for still another reason: his prowess in crossing back and forth between three- and two-dimensions, demonstrating an adeptness in painting said to rival his command of sculpture.

This fall, with an unprecedented one-man show of new works opening at Legacy Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, and an accompanying retrospective — John Coleman: Past/Present/Future — running from September 2016 to May 2017, at Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, the autumn of 2016 represents the most momentous season in Coleman’s career.

“We’ve had the good fortune of representing great artists over the years, but this event for John is bigger than anything we’ve ever done,” says Legacy founder Brad Richardson, noting that 15 new Coleman paintings and drawings will be featured, along with five new pieces of sculpture.

Spirit • Lives • Legends, the name of the Legacy show, is the culmination of five years of planning, with Coleman holding works he would normally send to the Prix de West Invitational and Cowboy Artists of America shows. It’s also his first event where paintings and drawings are the headlining acts, though the grand centerpiece is a 17-foot monumental version of his masterful, critically acclaimed bronze, The Rainmaker, One Who Brings Life.

That sculpture, which portrays a warrior firing an arrow into the sky, was created as a tabletop piece two decades ago. “Since that time, I’ve always felt it exemplified the main theme in my career, not just in its design but in the metaphor involving the story of the piece,” Coleman says. Smoke emanating from a sacred fire serves as a vehicle for conveying a prayer that’s symbolized by the arrow itself rising into the sky and piercing the clouds. Coleman says it represents a spiritual yearning not only for rain, but for life itself.

How can an artist articulate smoke with cast and cured molten metal? This, too, is part of Coleman’s visual alchemy.

Born in Southern California in 1949, Coleman grew up in a working class neighborhood an almost incalculable distance from his studio today in Prescott, Arizona — a creative space that seems to emanate from the age of the Enlightenment.

Early in his childhood, Coleman contended with a form of dyslexia that gave him an aversion to reading yet led him to cultivate his other creative senses — an ear for music, an expansive vocabulary and a penchant for conceptualizing bold ideas visually. Classical music fuels him in the studio; he is known amongst colleagues and collectors for speaking in colorful metaphors about art and life; and he sees his creations in the ether of his mind long before a graphite tip reaches the paper.

“My learning disability made high school extremely difficult, but it somehow endowed me with the ability to see images in my head,” he says. “It wasn’t until years later that I realized everyone didn’t do this. The thing that defined me as a child and in the eyes of my friends was that I was the guy who could draw anything. In terms of self-esteem, this was the thing that saved me.”

In high school, Coleman was informed he could drop out or stay in school knowing he wouldn’t graduate. Some faculty had written him off, but by kismet he fell into the company of a kindred champion. “I was fortunate that my art teacher, Mr. Schick, believed in me and suggested I spend my last year in high school taking several periods of his art class. He also arranged summer classes at Art Center College of Design and Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. As a result, I was offered a job illustrating a column by George Masters, who was a famous Hollywood hair stylist with many famous clients.”

Coleman and his high-school sweetheart, Sue, married while still in their teens. Although Coleman aspired to land an illustration job in Disney Studios’ animation shop, the couple got sidetracked by necessity — trying to make ends meet and get bills paid, running a series of entrepreneurial businesses and having kids. Eventually, they resettled in Arizona. Along the way Coleman began to drink heavily, forcing a reckoning that, in hindsight, he sees as being given a second chance.

While he may not have been physically practicing his art, approaching sculpture and drawing continued to mentally incubate. “I had spent 20 years developing a spiritual reverence for the act of creating art. And, from age 19 until I was 43, I hadn’t been doing any art between. But the poetry part — how I visualize the world — never left,” he says. “To be honest, I wasn’t in a position to pursue my dream of having a career in art because I wasn’t ready.” He admits that personal adversity became a potent catalyst. When Coleman poured himself into art again, it commenced a rebirth.

“For all of us, life brings us to plateaus and that’s when disappointment sets in. But I had an epiphany. I learned that when you reach a plateau it’s time to begin reaching for the next one. Growth and life are synonymous with each,” he adds. “If you aren’t growing, you are dying. I’m not claiming I understand where the journey leads, but I embrace the unknown as the known. We need to be willing to step out of our zones of comfort.”

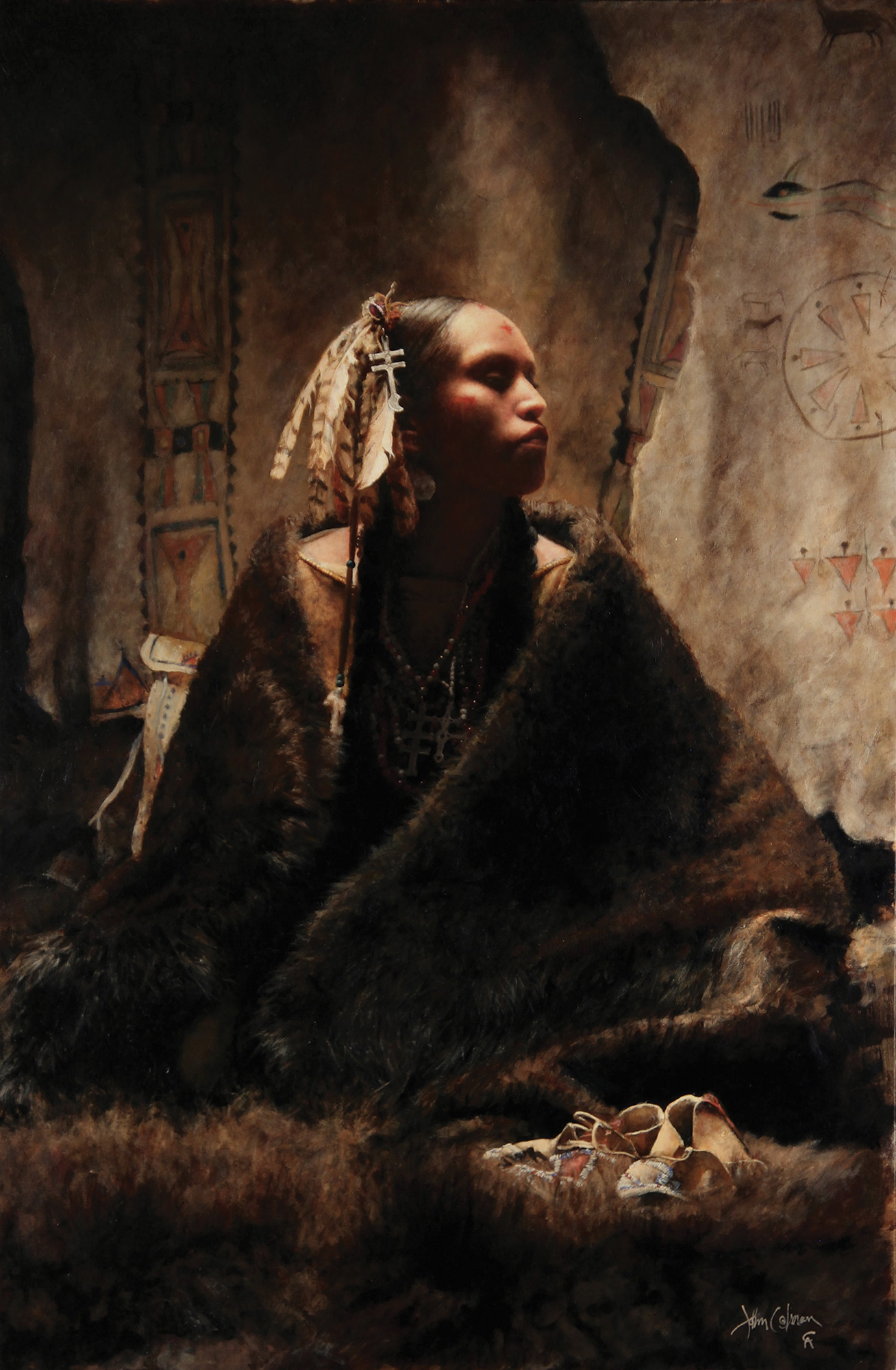

In the Legacy show, Coleman’s flatwork parallels his sculpture with similar explorations of mythology and compositional complexity. Bride of the Chief, for example, utilizes the strength of the pyramid shape, a motif commonly found in Madonna paintings of the Renaissance. “The design helps to accentuate the strength and complements the softness of the bride’s face. Behind her hangs an exploit robe which tells the story of her people. The moccasins in the foreground are the connection to her husband,” Coleman says.

Another drawing, Pow Wow with the Little People, explores the legends of “Little People” which proliferate throughout Indian Country. Native people have praised him for respectfully presenting the essence of tribal mystics.

Coleman considers American George Catlin “the father of Western art,” renowned for his opus of hundreds of different Native American portraits, painted on location in the 1830s and featuring people from 50 different plains tribes. Around the same time, Swiss artist Karl Bodmer traveled up the Missouri River, following in the tracks of Lewis and Clark and amassing a portfolio of landscapes, tribal and wildlife scenes.

Fascinated by those troves, in 2004 Coleman embarked upon an ambitious project that he called Explorer Artists: The Bodmer-Catlin Series. He created 10 bronze works inspired by five paintings of each artist and cast in editions of 35. With Legacy’s Richardson serving as his primary representative, five different museums — including the Joslyn in Omaha, Nebraska, and the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma — acquired entire 10-edition sets. According to Richardson, one set of 10 sold to a collector for $350,000.

The series established Coleman’s virtuosity and resulted in him landing a coveted monument commission. His portrayal of Black Moccasin, second chief of the Hidatsa tribe and a friend of Catlin’s, was installed at Catlin’s Brooklyn, New York, gravesite in July 2012. It commemorated Catlin’s 216th birthday and Coleman’s own 63rd.

Within Western art, few have successfully excelled in both sculpture and painting. Perhaps the greatest living example is George Carlson who has won the Prix de West grand prize in both media. “George Carlson is a genius in his traditional approach to form and surface,” Coleman says. “I have tremendous reverence for what he does.”

Eloquence in communicating an artistic idea is everything, he explains. “Although my style, unlike George’s, may contain the elements of details that risk weighting the art down, I found that when done in a certain way, they act as complements. The test of any good composition is that when a part is covered or taken away, the work should suffer for that. If it doesn’t, that means that you’ve just added an extraneous detail that serves nothing more than to distract.”

Strains of classicism run through Coleman’s work. He proudly touts his membership as a Fellow in the National Sculpture Society, founded in 1893 by Daniel Chester French, Augustus St. Gaudens, Stanford White and John Quincy Adams Ward, who set the standard for homegrown monumental sculpture in America. “My heroes are from that early period who created in the Baroque style,” Coleman says, pointing out that he, like them, draws and sculpts from live models. “I can only hope that my work withstands the test of time as theirs has.”

Another proud achievement, he says, was being voted into the Cowboy Artists of America (CAA). From a panel of CAA jurors, Coleman was awarded the Gold Medal for his life-size sculpture, Addih-Hiddisch, Hidatsa Chief, part of his Bodmer-Catlin Series, which was purchased for the Phoenix Art Museum.

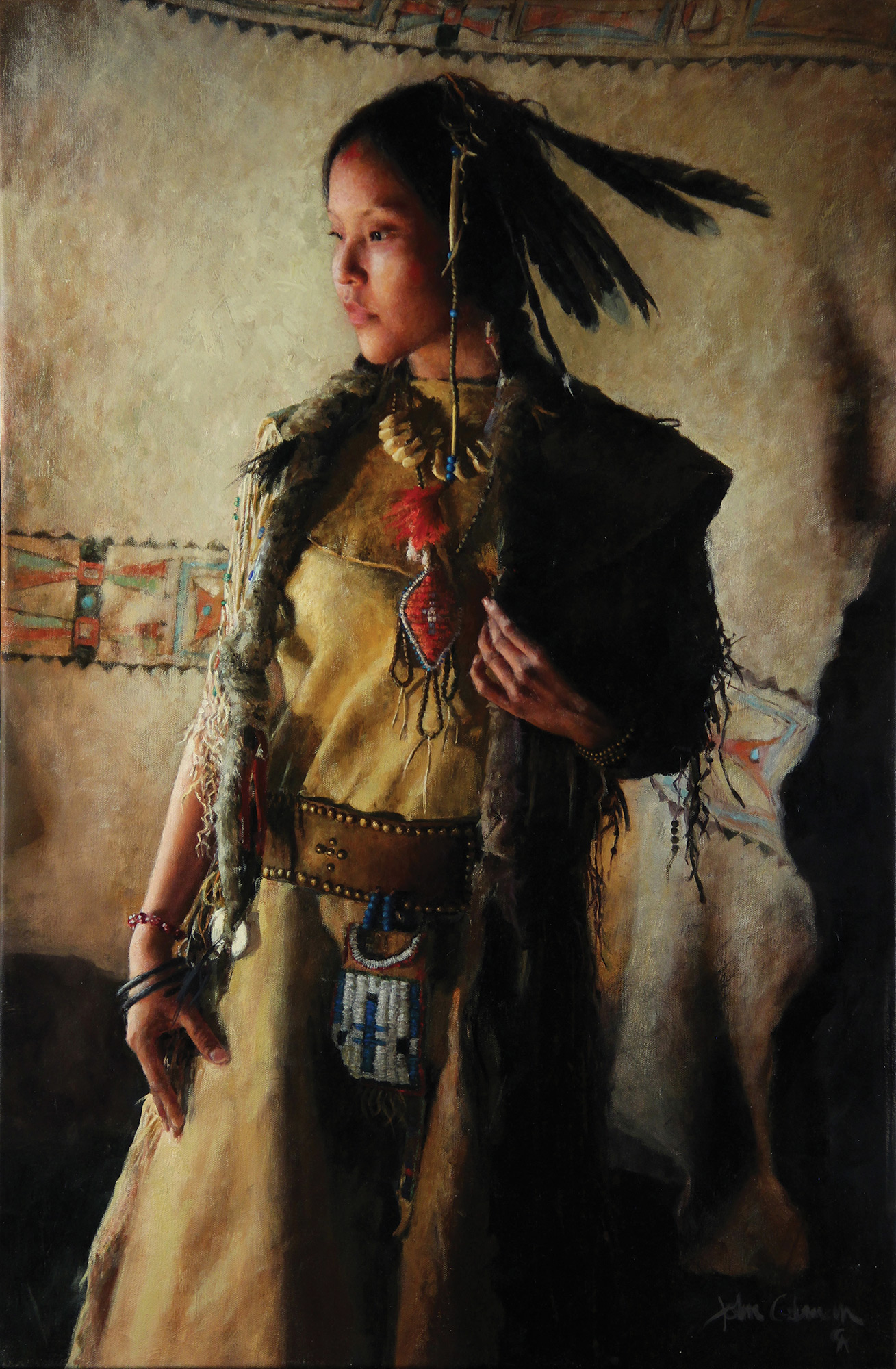

Coleman’s portrayals of native children have always struck a chord. “For me, it’s about looking deeper into the face of our common humanity and seeing it most purely in the expressions of a child. At a point long ago, all of us in the world were connected to the same genetic origin and from there we fanned out across the land,” Coleman says. “The indigenous people of North America are reminders of our own inherent need to live closer with the Earth that sustains us. Their relationship is traditional, it echoes in their ceremonies and it’s spiritual. In our hearts we recognize it.”

Whether ancient Greco-Roman sculptors probing their own mythology to make allegorical statements about human values, or rock artists in the four corners of the globe fashioning totemic figures, artists have long explored the transcendent power of religious themes.

Coleman believes the reason why people relate so universally to Native Americans, and why, as artistic subject matter, archetypal portrayals resonate so intensely, is because the visual image speaks an existential truth. The truth is that we human beings are a direct reflection of elemental life forces all around us — something more commonly recognized as Mother Nature.

“When you are creating an object that is similar in shape to something that is alive, you have an opportunity to cement an emotional bond and engender empathy,” Coleman says. “To me, it’s always been about more than the subject. I want viewers to feel something, as if we are kindred spirits drawn to the same imagery, sharing the same longing for connection. It’s an old idea, an old yearning, and everyone has it.”

Coleman is grateful to his loyal followers who have proved pivotal in his rise. Back in 1994, he received a phone call telling him a couple from Chicago might be interested in collecting his work. Not long afterward, Howie and Frankie Alper, known for their discriminating tastes, travelled to his studio. The Alpers and Colemans hit it off immediately. Loving his work, Mr. Alper struck a deal with Coleman: If he agreed to give them the first piece of every work cast, he would buy every sculpture Coleman ever produced.

“When I say that Howie and Frankie are my number one collectors, I’m not exaggerating,” Coleman says. “They are great friends, confidants, supporters and extremely philanthropic. They were instrumental in bringing the Scottsdale Museum of the West to fruition.” In fact, the Alpers plan to bequeath 95 Colemans to the museum to bolster the core of its collection.

“John shows emotion and you can see the soul in his compositions. The elements are exciting and in many pieces there is a delicacy, a grace and a dignity,” 87-year-old Howie Alper says.

“I love the stories he tells,” adds Frankie. “He does so much research, it’s unbelievable. There’s no one else like him.”

For years, the Alpers had been trying to purchase one of the rare paintings Coleman produced each year but they were unsuccessful in landing them at sales-by-draw events sponsored by the Autry, CAA, and Prix de West. “The boxes with the bidding slips were always full and our name never got pulled,” Howie notes.

A few years ago, Frankie threw an 85th birthday party for her husband in Arizona. As a special surprise, she invited Coleman. When the artist strolled in, he carried a coveted oil painting of a native shaman as a gift in homage to an elder collector. “It was an emotional moment when he handed the painting to Howie,” Frankie said. “They both had tears in their eyes.”

Coleman’s first rule is to “leave room for the viewer”, meaning that by working with softer impressionistic edges in his sculpture and painting, it invites viewers to read their own imaginations into a piece. He is known for garlanding his three-dimensional works with harder-edged, ultra-realistic accents.

His method is to work on all parts of a piece holistically rather than approaching composition incrementally, developing strong areas of mass and then tending to weaker spots later. “I like to get the piece into a place of strength, where it is starting to live and then I start to punch it (working more quickly) with details and texture,” he says.

With several different works in various “stages of becoming” in his studio, and with classical music filling the space, Coleman riffs on how creation is a total sensual experience. “I am fascinated how music can convey a mood without lyrics and have often thought sculpture lends itself to that idea,” he explains. “I have always loved history and mythology and feel they are the lyrics to my sculpture; the musical interpretation that engages the emotions. Just as music has a beginning, a middle and an end, so does sculpture, so does painting.”

Bill Anton says Coleman thinks and speaks abstractly, metaphorically, and that he sculpts and paints the same way which gives him a depth lacking in many of his contemporaries who approach subjects literally almost as documentarians.

“Enthusiasm and talent are essential, of course, in the making of visual art; they feed off each other,” Anton says. “If they're combined with disciplined work, something special can happen. John Coleman has put in a lot of time and study, yes. But there's something else; He is incurably curious. When he finds something inexplicably compelling, he’ll unravel the reason by relentless self-examination. If it can be said that there's more to a subject than what can be seen with the eye, then John is an explorer of that negative space between what is articulated and what is left to the imagination.”

P.J. and Bobby Hillin, Sr. of Fredericksburg, Texas, have been fixtures at Western art shows and they’ve toured many of the premiere fine art museums in the world. “I knew a lot of the established artists because I had been collecting their work. When John arrived in the early 1990s, I didn’t know a lot about him, but when I saw his sculpture I was astonished,” Bobby, a well-known businessman and fan of auto racing, says. “In my opinion, no other Western art sculptor comes anywhere close to delivering the degree of detail he does. Whether its sculpture or painting, the personalities of John’s subjects come through. I know what looks right to the eye and he never gets it wrong.”

Another area where Coleman has gotten it right is with his soulmate and wife of 48 years, Sue, whom he considers his most trusted friend and astute critic who more than anyone else has affected the high standard he’s established for his work.

Given all that he’s been through, Sue regards her husband as a miracle. “The struggles that he’s faced and yet he’s survived and gotten through it all and come out the other side a better person,” she says. “I have so much respect for him as a human, seeing how his mind works, unlike anyone else I’ve ever known. It takes me a while sometimes to catch up with where he’s at. It’s hard to put into words. His creative being is ethereal.”

Looking back on the course that brought him here, Coleman says much of it was a matter of finding his true voice. “My first ambition was to become what I reckoned was a true artist. A true artist is one who chooses a vocabulary to communicate ethereal ideas. It is said that a poet concerns himself less of words and more of the spaces between them,” Coleman suggests. “The main point is that art isn’t created until the artist has something to say.”

This fall John Coleman’s getting solid confirmation his admirers are listening. The Western art world isn’t only celebrating his presence; it’s paying heed to the narratives of a master making an uncommon crossover of media. And many are convinced the best is yet to come.

- “Bride of the Chief” (detail) | Oil | 50 x 33 inches

- “First Chief” | Oil | 23 x 34 inches

- “Pow Wow with the Little People” | Charcoal on Paper | 25 x 16 inches

- “Summer Blossom” | Oil | 36 x 24 inches

- “He Who Jumps” | Bronze | 25 x 18 x 8.5 inches

- “Pow Wow with the Little People” | Charcoal on Paper | 25 x 16 inches

- “Bride of the Chief” (detail) | Oil | 50 x 33 inches

No Comments