09 Jul Democratizing Beauty

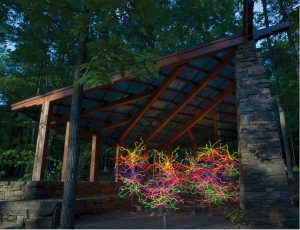

Glowing at the westernmost point of a long plaza, a mass of golden glass tentacles absorbs and diffuses the last rays of the sinking sun. A giant tower of blue glass shoots up between the broken stones of an ancient city. Floating like huge freshwater jellyfish in a still lagoon, translucent glass orbs are multiplied in the reflective waters.

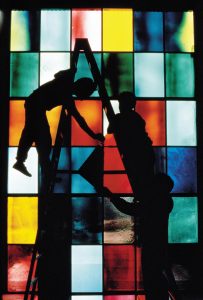

Artpark Installation #7, in collaboration with Seaver Leslie, 1975, 18 x 10 feet, Lewiston, New York, ©2021 Chihuly Studio. All Rights Reserved

Dale Chihuly is famous for his groundbreaking blown-glass sculptures. Drawing on forms from nature, craft, and art history, he extends techniques developed by glass artisans from the Roman era to the present. Whether rippling like sheets of frozen water, enclosing space in a perfect sphere, or reaching out like the fingers of a fantastic sea creature, his luminous sculptures are breathtakingly beautiful. Taken individually, they have changed the face of glass. But by grouping them in gardens, plazas, train stations, canals, and architectural masterpieces, Chihuly has also changed the face of public art.

Prior to Chihuly, glass had its architectural uses. […] But while it has become an indispensable, architectural element, glass has an inherent fragility that seemed to make it an unlikely candidate for public art.

Chihuly has changed all that with his enchanting environmental installations. […] Whether arranged in interior or exterior spaces, his sculptures are transformative. Sensitive to the shifting illumination and interactions with various kinds of space, they create an immersive experience. Chihuly’s glass sculptures bring an organic vitality to stolid architectural structures and an intriguing mix of nature and artifice to garden settings. And they rely on an element of surprise — viewers wonder, as if presented with a magic trick, how can glass do that? How can light and color be turned into something tangible? How can something solid seem so fluid and alive?

Chihuly’s installations are distillations of a lifetime of travel, experimentation, and exposure to the long and varied history of glass. His journey started in 1941 in Tacoma, Washington, where he was born to George and Viola Chihuly. Chihuly recalls, “My dad got fortunate to get out of the coal mines and moved to Tacoma and became a butcher.”

Although he would subsequently travel the world and range widely across human history, Dale Chihuly has remained a denizen of the Northwest and today maintains his Boathouse studio in Seattle. […] Always a restless wanderer, Chihuly had a peripatetic education: He took a weaving class at the College of Puget Sound for a year; studied weaving, interior design, and architecture at the University of Washington; and then left school to travel in Europe and Israel. A stint in a kibbutz injected him with a sense of purpose and the prodigious work ethic that has characterized him ever since.

Artpark Installation, in collaboration with Seaver Leslie, 1975, Lewiston, New York, ©2021 Chihuly Studio. All Rights Reserved.

Back at the University of Washington, he turned his attention to glass, creating woven tapestries with shards of glass. A year later, he accidentally discovered the magic of glassblowing. He recalls, “One night I melted a few pounds of stained glass in one of my kilns and dipped a steel pipe from the basement into it. I blew into the pipe and a bubble of glass appeared. I had never seen glassblowing before. My fascination for it probably comes in part from discovering the process that night by accident. From that moment, I became obsessed with learning all I could about glass.” After a few detours that included work as a commercial fisherman for a season to pay tuition at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, he completed a glassblowing program there, followed by a second master’s degree, at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

Chihuly and Architecture, 2021. Book co-distributed by Abrams ©2021 Chihuly Studio. All rights reserved.

Then came the most important educational experience of his life. In 1968, Chihuly went to Venice on a Fulbright Fellowship to study at the prestigious Venini glass factory. Located on the island of Murano, this studio has been instrumental in reviving and sustaining traditional glassblowing techniques that might otherwise have been lost. There, Chihuly observed the rewards of teamwork, a lesson he would later apply to his own practice.

Palazzo di Loredana Balboni Chandelier, 1996 ©2021 Chihuly Studio. All Rights Reserved.

In 1969, back at RISD, he founded and taught in a glass program while dreaming of a more focused kind of training. This came to be in 1971. While running the glass program during the school year at RISD in Providence, he also established the Pilchuck Glass School in Snohomish County, Washington State, north of Seattle, as a summer school. At first a rough-and-ready affair, Pilchuck has since developed into an internationally renowned school and glass workshop.

Then tragedy struck. In 1976, a car accident left Chihuly blind in one eye, and in 1979, he dislocated his shoulder in a bodysurfing accident. No longer able to blow glass himself, he stood back and directed a team of glassblowers. In 1983, he returned to the Pacific Northwest, where he has continued to conduct a team of assistants in the creation of the beautiful glass sculptures for which he is now internationally known. […]

While he was entranced with process and transience in his early works, Chihuly was also exploring the union of sculpture and architecture that would characterize his later installations. Blown, cast, assembled, and mosaic glass formed the basis of a series of convention-defying doors, walls, and windows. These abstract designs, with their references to Art Nouveau and mid-century aesthetics, revealed Chihuly’s interest in the history of art and design.

In 1980, he was offered his first architectural commission, to design windows for the Shaare Emeth Synagogue in St. Louis. […] By then, Chihuly had also begun to create the freestanding glass sculptures for which he is best known, starting in 1975 with a series of Cylinders in which glass thread drawings were fused onto molten bubbles. For a time, he put aside his interest in installations. But he carried with him the lessons he had learned from these early experiments about the drama of light and space, the interplay of architecture and glass, and the role of viewers in activating an environment.

Boathouse 7 Neon, 2016 ©2021 Chihuly Studio. All Rights Reserved.

In focusing on individual works, Chihuly was also building a visual vocabulary from which to draw when he returned to installation. He works in series, and these reveal his omnivorous interests. He digs into art history, explores the often amazing shapes and colors of the natural world, references both Western and non-Western aesthetics, and pushes glass to the limits of what it can do. A brief survey of his series reveals the building blocks that go into his environmental installations.

The first, following the Cylinders, was the Baskets, whose reference to the woven containers created by Northwest Coast Native Americans is a nod to his Western roots. These abstracted vessels have the slumping asymmetry that he observed in baskets at the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma. They aren’t really baskets, but they contain the memory of baskets, just as his first glass works contained the memory of [Navajo] weaving. […]

Monarch Window, 1994 | 22 x 40 x 3 feet | Union Station, Tacoma, Washington ©2021 Chihuly Studio. All Rights Reserved. Photographed by Scott Mitchell Leen.

Chihuly’s installations have taken him around the world, through the history of architecture and public space, and into the hearts of a vast public. He has proved that beauty is contagious, and glass is magic. He has also confirmed the status of glass as a social medium. Once so precious that it was restricted to the palaces of kings or submitted to the service of God, the art of glass now belongs to us all.

Editor’s Note: Excerpted from the book Chihuly and Architecture. (Abrams, 2021).

No Comments