09 Jun Ethos

More than 20 years ago, on the first morning I ever interviewed Ted Turner, the famous “media mogul” was in the nascent stage of assuming a new identity: Western “bison baron.” Turner, the pioneering founder of 24-hour news, stood in front of a plate-glass window and directed my attention toward a distant green pasture at his Flying D Ranch in Montana.

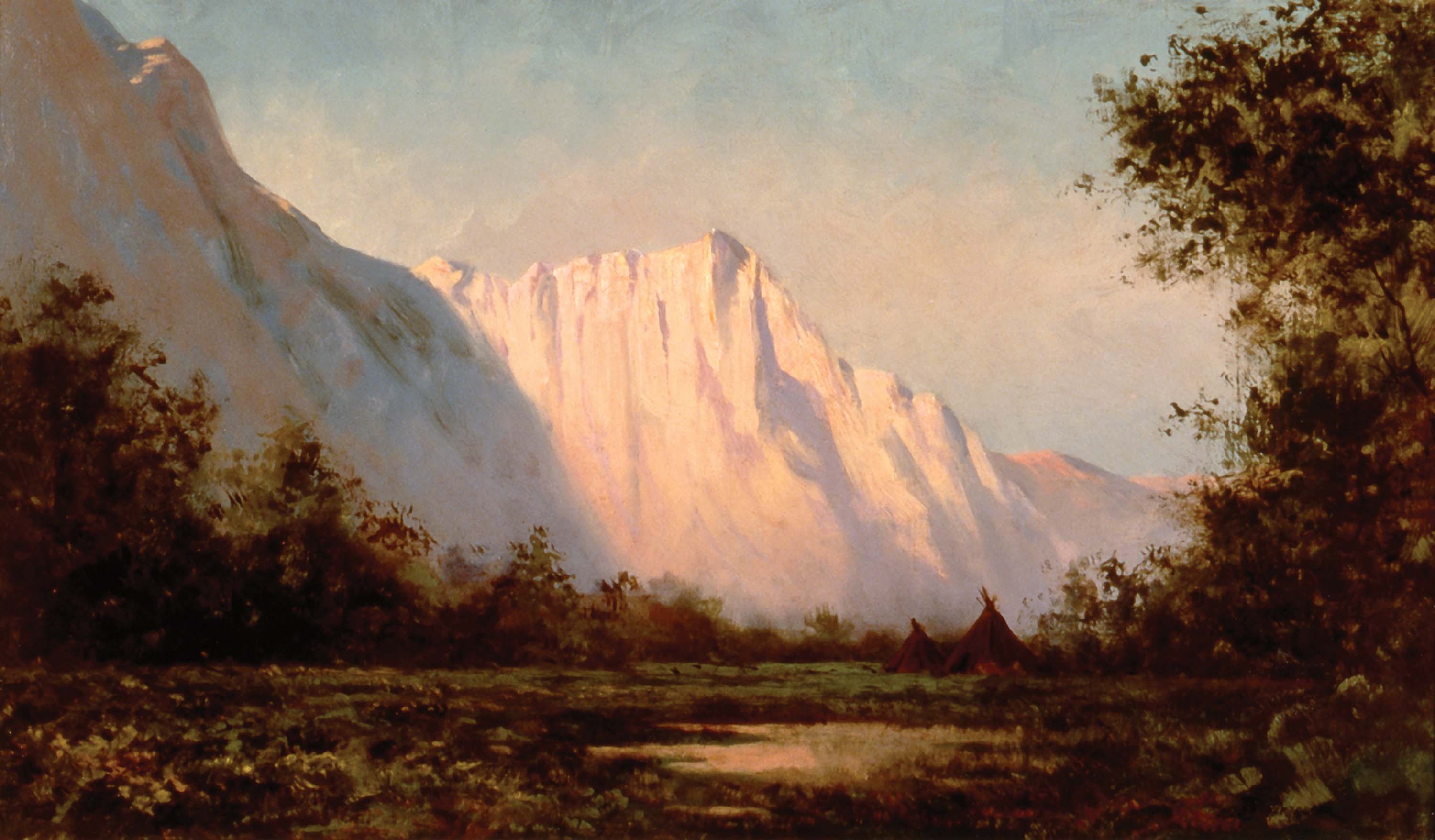

Miles away, a herd of bison peppered foothills in the Spanish Peaks, a northward trending, white-summited spur of the rugged Madison Range. Once Turner had my attention, he motioned back into his rustic living room where we were standing. He pointed to artworks by Albert Bierstadt, Karl Bodmer and George Catlin.

Romantically conceived, and in some ways documentarian in their portrayals of the West, they were originally created during the 19th century when the region was still wild — prior to the human-caused, near annihilation of 35 million iconic bison; elk, deer and pronghorn herds; enclaves of bighorn sheep and mountain goats; grizzly bears, wolves, beaver and trumpeter swans, among a larger litany.

In response to my question — “Mr. Turner, what is the vision you have for your property?” — he alluded to a mood of enchantment that still radiated from the artistic surfaces. He said, “I want my land to look and feel like those.”

What most readers may not realize is that art has always served as a powerful reference point for Turner, who regards the West as his second home. One of the childhood experiences he has vivid memories of was traveling to New York City with his father. As the elder attended business meetings, Turner, then a boy, was left to roam through Manhattan on his own and found himself wandering through the Metropolitan Museum of Art and American Museum of Natural History.

Once upon a time, the legendary entrepreneur had also been an aspiring painter. Today, with world leaders touting him as a forerunning “eco-capitalist-humanitarian,” art still informs his landscape-level thinking. “Great art not only speaks to what once was, but it reminds us of what still can be,” he says. “I don’t collect art to dwell in the past. I think it can motivate us to want to live in a better world.”

With two million acres under deed, Turner is the second largest private property owner in America. His herd of bison, now 55,000 animals strong and scattered across six Western states — Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Kansas — is the most ever stewarded by a single individual. He is using his ranches, plantations in the Southeast U.S., a barrier island off the coast of South Carolina, and three estancias in Argentina as “arks” for protecting and restoring imperiled species.

At the Flying D alone, a spectacular former cattle ranch near Bozeman that suffered from decades of overgrazing by beef cows, he can make a claim that few others in the Lower 48 can: All of the native mammal species that likely existed on the ranch in the dawn of the post-Pleistocene ice age, have appeared there again over the last generation.

Turner is indeed a savvy art collector whose preferences run traditional and classic. Seldom has the body of work been on public display. At the turn of the millennium, the prestigious High Museum of Art in Atlanta featured Visions of the Frontier: American Landscapes from the Collection of Ted Turner for a limited run. A short while later, the Museum of the Rockies, affiliated with Montana State University in Bozeman, gave Westerners a glimpse of 13 heralded works owned by Turner under the title In Western Light: The Paintings of Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran.

Short of traveling to all of Turner’s far-flung properties, readers can get a taste of his collection at perhaps an unlikely series of venues: the tycoon’s Ted’s Montana Grill restaurant chain, co-founded with nationally respected concept-eatery guru George McKerrow Jr.

With 44 Ted’s Montana Grills across the country, McKerrow says that art plays an important role in exuding the ethic of “Eat great. Do good.” that the restaurant aims to communicate to patrons. “What the artworks speak to is American authenticity, places in the landscape where your heart tells you you want to be,” the Atlanta-based McKerrow told me one afternoon at a Ted’s Montana Grill in Bozeman.

He pointed to a reproduction of Bierstadt’s gloaming 1887 oil, Deer at Sunset, the original of which appeared in the museum tour. He also walked me over to Bierstadt’s Buffalo on the Montana Plains, oil on paper, painted in the few years after Yellowstone National Park was created in 1872 and George Armstrong Custer met his demise at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Buffalo on the Montana Plains reads visually as a dreamlike meditation by an artist who knew a frontier that once held wildlife plenitude was vanishing. Ted’s Montana Grill, which features bison on the menu, is all about using the platforms of good conversation and good meals to reflect on where America is in the 21st century, where our food comes from and how art draws people together into a common vision, McKerrow and Turner say.

Several years after my inaugural conversation with Turner, among a succession that resulted in my new book, Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet, in which I visited nearly all of his major wildland properties, we were in the living room of a ranch chatting with his guests prior to dinner.

Rising above us was a massive work by Bierstadt, Yosemite Valley, that is similar in scale to masterpieces in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

“Do you notice anything peculiar about it?” Turner asked his friends.

Turner had acquired the piece in a bidding war. When the visitors could not provide an answer, he said,

“Instead of searching for something that’s in the painting, try to identify, if you can, what it is that Bierstadt left out, and remember, he painted it in 1866.”

Historians often speculate about decisions that artists make, sometimes to convey an allegorical message. Bierstadt, as with poet Walt Whitman and thinkers of the age, had been emotionally traumatized by the carnage of the Civil War, Turner said.

Boys who left their small farming communities returned home from battlefields as somber men turned inward upon themselves, missing limbs, spooked in their dreams by horrors they had endured. Not unlike the veterans who have come home from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Turner’s guests were rapt. “If you’ll notice, it’s a breathtaking view of Yosemite Valley not far from the banks of the Merced River, but there are no animals, which is uncharacteristic,” he explained. “Bierstadt loved wildlife but with this easel painting he left it out. I’ve been told that it was his way of conveying the emptiness that landscapes have when there are no living things moving through them. It was his response to the ravages of the Civil War. Some men did not return home and it created a huge void.”

Turner didn’t know the full exegesis of the work until after he acquired it. There have been many nights when he’s awoken and wandered into his living room, pondering its timeless message. He believes that Bierstadt presciently painted the Yosemite scene as a dare to generations that followed to reflect on thoughtless violence committed against Native Americans, bison and myriad other creatures.

Mike Finley, head of the Turner Foundation and former superintendent of both Yosemite and Yellowstone national parks, has also studied the work. Something else, he says with a laugh, is missing from the valley: human structures, large crowds and auto congestion. He invokes the wisdom of John Muir, who warned that pieces of paradise can, if not properly stewarded, be literally loved to death.

Quoting Muir, Finley says that entering the valley is equivalent to worshipping before a vast natural grotto. The spirituality of the experience is no different than setting foot inside a medieval cathedral or listening to a live opera performance in which there is a finite number of seats available to the viewer.

Today, only a few paces away from the Bierstadt painting, sitting on a table in Turner’s living room, is another scene from Yosemite Valley. This one is a version of the famous black-and-white photograph taken of Muir and Theodore Roosevelt standing over the valley. A friend gave Turner the photograph but had his profile superimposed into the scene, making it appear as if Turner had joined company with the forerunning American conservationists.

“They lived a century apart from each other, but Ted deserves to be portrayed in their company and them in his,” Finley says. “Muir and Roosevelt ushered forth the conservation movement and Ted has given it new meaning. We’re in the picture, between the frame, all of us, creating art that speaks to our time.”

- Albert Bierstadt, “Buffalo on the Montana Plains” Oil on Paper (laid down on canvas) 14 x 19 inches | ca. 1878-1882

- Jules Tavenier,” El Capitan” Oil on Canvas | 18.25 x 31.25 inches

- Albert Bierstadt, “The Last of the Buffalo” Oil on Canvas | 30 x 44 inches | 1888

- Thomas Moran “The Grand Canyon – Hance Trail” Oil on Canvas | 20 x 30 inches | 1904

No Comments