10 May Formed and Fired

What happens when a community comes together and decides for themselves how they would like their histories and cultures represented in a museum setting? Well, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico, has the answer to this, and it’s titled Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery. After being on exhibition in Santa Fe through May, it will open at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Vilcek Foundation in New York City this July, before traveling to Texas and Missouri.

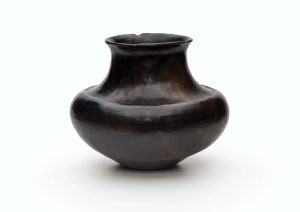

Santa Clara Water Jar | Clay | 11 x 13 inches | c. 1900 | IAF.269 | Collection of the School for Advanced Research | Photo Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research

Culled from the legendary collection of the Indian Arts Research Center at Santa Fe’s School for Advanced Research (SAR) as well as the perpetually active Vilcek Foundation, the 100-piece exhibition of historic and contemporary Pueblo pottery was curated by the Pueblo Pottery Collective, a group made up of 60 individual members from 21 pottery-making tribal communities in New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas.

The Pueblo Pottery Collective was organized in 2019 for the distinct purpose of curating this exhibition. Members of the collective — including artists, activists, museum professionals, and community members — were tasked with selecting and writing about “artistically or culturally distinctive pots” from both collections to be included in Grounded in Clay.

Tamaya Srpu’na (Canteen) | Clay and Paint | 11.5 x 8 inches | c. 1800 | IAF.558 | Collection of the School for Advanced Research | Photo Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research

“The approach to this exhibition illuminates the complexities of Pueblo history and contemporary life through the curators’ lived experiences, redefining concepts of Native art, history, and beauty from within, confronting academically imposed narratives about Native life, and challenging stereotypes about Native peoples,” says Elysia Poon, the director of the Indian Arts Research Center at SAR, and a member of the collective.

Works of art in the exhibition date from pre-contact to the present day and include everything from the complex and abstract black and white designs of a 1,000-year-old ladle found in the Mesa Verde area, to a utilitarian Hopi canteen from the latter part of the 19th century, to Jeralyn Lujan Lucero’s (Taos Pueblo) figurative sculpture from the mid-1990s depicting a woman holding a pot made from micaceous clay and turquoise.

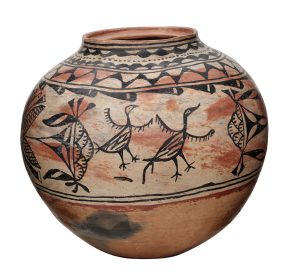

Tesuque Jar | Clay and Paint | 15.5 x 17 inches | c. 1870–80 | VF2016.01.08 | School for Advanced Research | Photo Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research

In 2017, Brian Vallo, then the director of the Indian Arts Research Center at SAR, was asked to help curate the exhibition of the prestigious Diker Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While working on the Diker exhibit, Vallo proposed the idea of Grounded in Clay to the Met curators and they were intrigued. Vallo left SAR after being appointed governor of Acoma Pueblo, but his predecessors continued with the project, eventually creating the collective responsible for the curation of the exhibition and, ultimately, the exhibition itself.

“What I really appreciate about Grounded in Clay is that it was curated by the Pueblo people themselves,” says Vallo. “They identified the pots, they wrote labels, contributed to the catalogue, and have actively engaged in ongoing programming. The exhibition is truly a beautiful way to present these pots. Some are ancestral, some historic, and a nice selection of contemporary; so it’s just a beautiful mix of traditions with the voice of the Pueblo people themselves. As the exhibition travels, some of it will change, but the core of the show is this voice of the Pueblo people. And that is why it opened in New Mexico. We wanted these community members to see it first.”

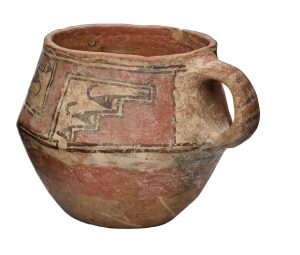

Tamaya Tah’s (Cup) | Clay and Paint | 4.5 x 6.125 inches | c. 1750–60 | SAR.2010-6-1 | Gift of Samuel and Margaret Schwartz | Collection of the School for Advanced Research | Photo Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research

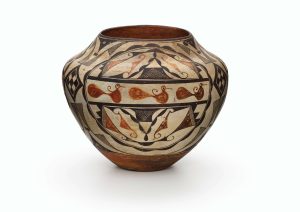

As a member of the collective, Vallo chose an Acoma polychrome storage jar from an unidentified maker for placement in the exhibition. Focusing on the beauty of the form of this 150-year-old vessel, Vallo says, “The master potter had the skill not only to form a jar this size, but to carefully execute other steps in creation, including a successful outdoor firing. The designs on both the neck and body are classic Acoma pottery patterns depicting clouds, rain, and corn fields. This jar sings loudly to me through its design and its lived experience in Acoma.”

Another member of the collective, Hopi/Tewa painter Dan Namingha, chose a bowl made by his great-great-grandmother Nampeyo in the first decade of the 20th century. For Namingha, the pot represents memories of his family creating pottery in the village of Polacca on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona.

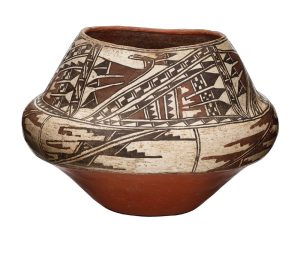

Zuni K’yabokya De’ele (Water Jar) | Clay and Paint | 9 x 13 inches | c. 1720 | IAF.1 | Collection of the School | for Advanced Research | Photo Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research

“My earliest memory of my great-grandmother Annie was probably from when I was around 4 or 5 years old. She lived alone. Her husband, Willie, passed away before I was born, but she continued creating pottery. She would sometimes sit near the window in the sunlight as she applied her intricate designs on her ceramic pots. She kept a few small pots in the woodstove, allowing them to dry before taking them outdoors for firing. She sold her pottery to visiting collectors and at the local trading post.”

Of this earth and directly from this earth, Pueblo pottery begins its life pulled from the ground that has been walked on by tribal members for thousands of years. As fragile pieces of formed and fired clay, the mere existence of these vessels today is a testament to the love, care, and honor they have been shown by their various owners throughout their lifetime.

Up until Grounded in Clay, most museum exhibitions that focused on Pueblo pottery — while well intentioned — took on the more traditional and generic perspective of historic and ethnographic understandings connected to the various movements and shifts in Western culture. These earlier perspectives characterized the work by family lineage within the specific Pueblos or as reactions to various Western technologies, such as the railroads, the influence of white traders, and the tourist trade in general. Grounded in Clay, however, looks at the artists behind each work and their relationship to the entire Pueblo community as well as the aesthetic elements of the work and what these designs and shapes symbolized and still symbolize for their people.

Acoma Water Jar | Clay and Paint | 10.25 x 12 inches | c. 1920–30 | VF2019.02.03 | Collection of the Vilcek Foundation | Photo Courtesy of the Vilcek Foundation

Jemez artist Kathleen Wall is a member of the collective and chose a 12-piece nativity scene made by her aunt Mary Toya to be included in the exhibition. For Wall, her aunt’s piece symbolizes not only the strong group of matriarchs — including her mother, grandmother, and aunts — who taught her to make pottery, but the communal process of making the pottery itself.

“The thing about Pueblo pottery is it’s never just about the pottery,” says Wall. “There is always something cooking in the oven, a pot of stew on the stove, children, and family in the room as well. So, it is not just the pottery; it encompasses the feeling of nurturing, the smells, the tastes, the family, everything. It is all there. In communal living, you are surrounded by it all.”

This communal idea extends to where the pottery is made as well. Wall lives on the Jemez Pueblo and her grandmother Carrie Loretto lived in a little adobe house on a hill that fell into disrepair and started to crumble back into the earth after she passed away. Wall decided to renovate the house little by little, and now, it is where she lives and where she makes her own pottery.

“Everyone who comes here to visit has a memory of my grandmother and this house,” says Wall. “They remember her standing in the kitchen, what she had on the stove, the food she served everyone, and how she made her pottery at the same time. And this is the idea we are trying to get across in Grounded in Clay. These works were made by real people, and we want the humanity to shine through. We know the historical facts, but that does not shed light on who these artists were, and what they created, and how the family and the community were integrated into that process. When I see a pot, I do not just see a pot, but I see the whole community, all of us; we all were taught to dig clay, taught to fire, taught to help in that process, so it is all there.”

This sentiment is echoed by another member of the collective, Joseph Aguilar (San Ildefonso Pueblo), who sees the exhibition as an attempt to connect the historical memories of the people involved with the history of the land and people of the region. For his contribution, Aguilar chose a Powhogeh storage jar from the 1820s.

Santa Ana Jar Clay and Paint | 10 x 12 inches | c. 1885 | IAF.848 | Collection of the School for Advanced Research | Photo Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research

“Grounded in Clay emphasizes the underlying, multifaceted, and nuanced understandings that the Pueblo Indian people of the American Southwest have one of the more ubiquitous and resilient forms of our material culture,” writes curator Aguilar. “Historical memories and our understanding of pottery and other cultural patrimonies are tantamount to a form of Indigenous intellect — a physical, spiritual, and intellectual worldview that is inextricably linked to land, people, and history.”

Poon took over as the director of the Indian Arts Research Center at SAR when Vallo left to become governor of Acoma but she is also a member of the collective. For Poon, what was most exciting about this project was how everyone came together to make it happen. “This was a pandemic process, so we only all met in person just recently at the opening of the exhibition,” says Poon. “Everyone was motivated to make this a successful project and to see everyone’s voices represented in some way was so exciting. It is wonderful to see all the vulnerability that was shared by everyone and how each curator was so willing to share personal stories and personal histories.”

While most museum exhibitions start with a theme and then typically a single curator chooses art to fit that theme, Grounded in Clay was organized completely in the opposite way. Each member of the collective chose one or two pieces to be in the exhibition and then members looked at the totality of the pieces together and then broke them down into themes. For Grounded in Clay, the four themes are: utility, ancestors, connections through space, and time and elements.

“The takeaway from the exhibit is that we wanted people to feel like they met the curators, met hundreds of personalities,” says Poon. We wanted to show that the people and the pottery are on the same plane. We want people to understand the relationship between people and pottery and the personalities behind each piece.”

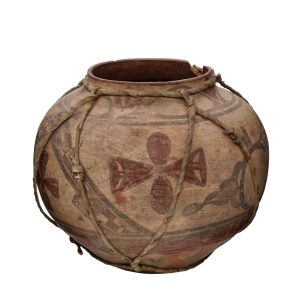

Tamaya Ah’sa (Storage Jar) | Clay, Paint, and Rawhide | 14 x 16 inches | c. 1895 | IAF.874 | Collection of the School for Advanced Research | Photo Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research

Ultimately, viewing Grounded in Clay brings home the simple truth that these are works of art created by actual people, people who lived and breathed and walked, had families, worked, cooked, slept, fought, raised children, grieved and loved, laughed and cried, all in close proximity to the work they created. The works of art in this exhibition were created at kitchen tables, living rooms, garages, backyards, and bedrooms, mainly in the company of many other family and community members. The work was done in those spare hours of the day, in between chores, after all the other work for the day was done, after the dinners were made, the children put to bed, the houses cleaned and swept and quieted for the night. They were made by moonlight, directly under the blue New Mexican skies, by candlelight, or whatever was being offered at the moment; done by people who knew the importance of what they were doing, understood why these simple shapes made of the earth were needed for them as well as the community at large and whomever else may find themselves in their presence sometime in the future. Like us, at this moment, being honored with this true gift that is the exhibition titled Grounded in Clay.

Grounded in Clay will be on exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Vilcek Foundation from July 13, 2023, until June 4, 2024. From there, the exhibition will travel to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, from October 27, 2024 through January 19, 2025, and finally the Saint Louis Art Museum in Missouri, March 9 through June 1, 2025.

No Comments