01 Aug From the Outside In

TURN WEST OFF STATE HIGHWAY 21 IN CENTRAL IDAHO and the granite walls of the South Fork Payette River canyon open to the pine-topped plateaus and rolling grasslands of Garden Valley. Admirers of the work of artist James Castle, Garden Valley’s celebrated native son, will recognize in this remote ranching community a region whose ruggedness is only offset by the values that have allowed it to thrive: homespun humility, hard-won optimism and a clannishness that prompted early 20th-century residents to embrace as their own a disabled farm boy who created castles in the air with such materials as sharpened sticks, soot and his own spit.

The Idaho artist is the subject of James Castle: A Retrospective, slated to open in October 2008 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The show, which will feature an impressive array of Castle’s soot-and-spit drawings, color-wash pieces, homemade constructions and handcrafted books in miniature, will be accompanied by a fully illustrated catalog and a documentary of Castle’s life and times. The retrospective, book and film are the latest in a series of accolades showered on Castle in the past decade that include exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York; Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago; and Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

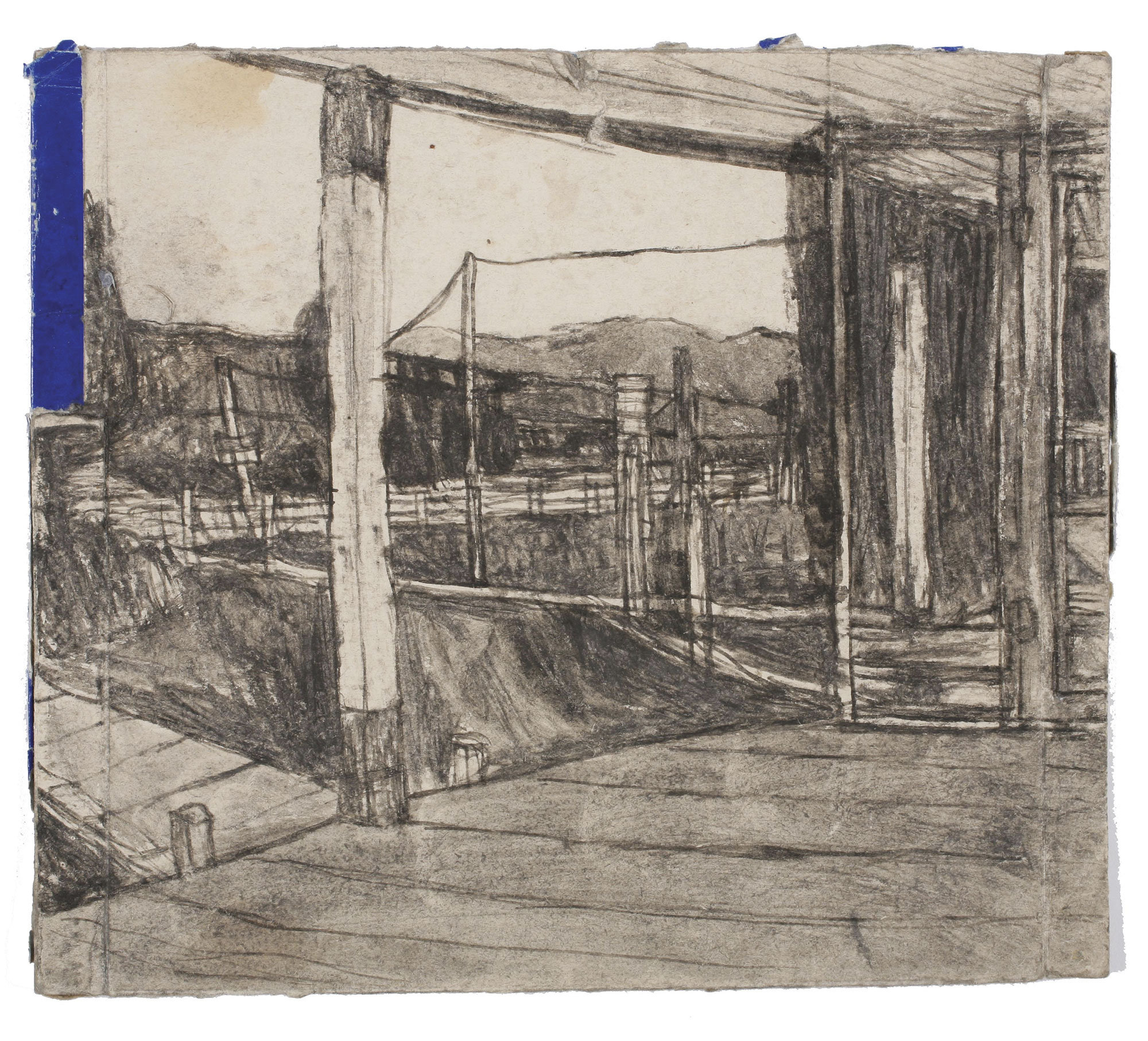

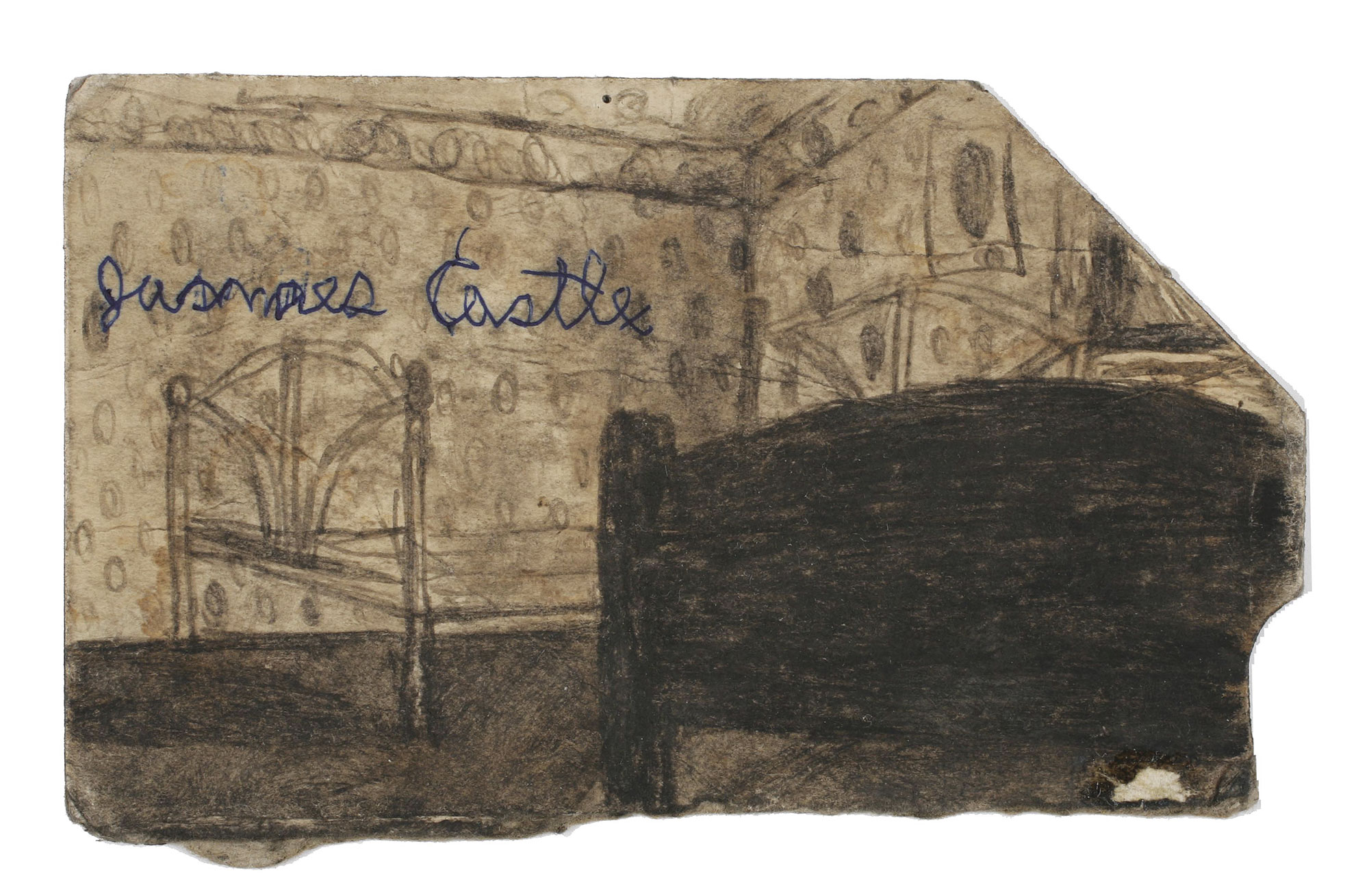

Castle (1899-1977) was the fifth of seven children born to a ranching couple whose farm served as Garden Valley’s post office-cum-general store. Afflicted by deafness, Castle evinced an early and obsessive interest in drawing. His imagination flourished in a host of sheltered environments, with the artist living mostly with family. It is a testimony to the force of his will that he spent five years at a school for the deaf — a fact recently uncovered by filmmaker Jeffrey Wolf — without learning to speak, read or write. Utilizing a rich array of found materials, including colored paper mashed and diluted to extract greens, blues and reds, and hoarding everyday items that came within his orbit, including postmarked envelopes and ice cream containers, Castle reproduced a universe that was peculiarly his own. We may recognize Garden Valley and Castle’s changing residential outposts — their exteriors, interiors, people and animals — but it is a Garden Valley transformed by an eternal observer whose principal expression is art. It is a farmhouse deconstructed into dreamlike design by an unknowing architect. It is an emptied attic room filled with the consciousness of an artist who, like the space, contains much more than meets the eye.

Castle the artist is as difficult to categorize as Castle the man is to capture. He is in a class of artists variously termed “outsider” or “self-taught” because they work outside — and often in contravention — to the dictates of academic art and because, like Castle, they often possess a physical, mental or geographic handicap that hinders formal training. Drawing on styles that range from the representational to the conceptual, and exploring the buildings, landscapes and living creatures of his environment, Castle’s versatility looms large in the small gathering of critically acclaimed self-taught artists. And, remarkably, examples of Castle’s work, all of which is undated and untitled, show that the artist apparently unraveled the puzzle of perspective, which, in the annals of art history, was not mastered for millennia.

Molly Dougherty, executive director of the Foundation for Self-Taught American Artists, the non-profit behind Wolf’s documentary of Castle, said the organization formed in 2005 to promote those sidestream artists whose work is viewed through the captivating but distorted lens of their biography. Dougherty is among those advocating a model for evaluating art that is meritorious. She says of Castle, “Some people are born with perfect pitch; he was born with true point perspective. Regardless of his disabilities, he was able to capture a time and a place and prove there are no barriers to artistic vision. He created this extraordinary body of work, beautiful drawings and constructions, and that’s where you begin.”

But it is not where you end. The arc of Castle’s posthumous popularity coincides with a growing appreciation for outsider art, a taste refined by the 1991 founding of Intuit, the launch of the first Outsider Art Fair in 1993 and the opening eight years later of a new building in New York by the American Folk Art Museum. Today, Castle’s pieces are included in the public collections of such august institutions as the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago.

What is distinctive about Castle’s climb to the highest reaches of the contemporary art galaxy is that his works could not have achieved ascendancy without the abiding faith of a select circle of family members, art experts and academicians. The figures who have brought Castle’s pieces from bundles and boxes stashed in attics and outbuildings have formed a chain of goodwill, with each link as vital as the next in ensuring Castle’s genius would be acknowledged — and, in some cases, independently of the biography that precedes him.

Tom Trusky, head of the Hemingway Western Studies Center at Boise State University and author of James Castle: His Life and Art, recognized Castle as a visionary in the mid-1990s. He worked with Castle’s niece, Geraldine Wade Garrow, to assemble and document the artist’s work until a rift abruptly ended the association. Trusky remains a controversial figure in the Castle saga for seeking to diagnose the artist, a preoccupation of contemporary biographers, and, unlike those who wish Castle’s work to be judged by its merit, Trusky believes to divorce Castle’s work from his disabilities is equivalent to evaluating Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with a Bandaged Ear without reference to the missing portion of the appendage. “When people say, ‘I just want to appreciate the work,’ that’s just silliness,” he says.

Before his fall from grace with Castle’s relatives, Trusky introduced them to Boise art dealer Jacqueline Crist, owner of J Crist Gallery, and it has proved an invaluable service. Crist is the force behind the phenomenon that is James Castle and if you recognize his work today it is because Crist, representative of the Castle estate collection, has ensured it. It is because of her tireless labors, impeccable choices and professional credentials — she is the former curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles — that Castle is at the forefront of the self-taught art field. The day in 1995 that Garrow brought a cardboard box of Castle’s work to Crist’s gallery was the beginning, she says, “of an amazing, incredible journey with the family” that has installed her as its champion and honorary member.

“People often ask me if I think he knew what he was producing was art,” says Crist. “My answer is, if the work had value to him and it gave him identity, ultimately, is it really necessary to know?” Crist shares with Castle a childhood steeped in rural Idaho, and that foundation gave her the insight to relate to what she describes as “an ordinary family with an extraordinary family member.” While Crist has come to feel that her career before the meeting with Garrow was an exercise in preparation to manage the Castle work, she adds, “But if the work hadn’t been great, nothing I could have done would have mattered.”

Unlike the prophet, Castle was honored in his own house and in his own land. An artist-nephew was the catalyst for the first exhibits of Castle’s work in 1962 at galleries in Oregon and a show at the Boise Gallery of Art — now the Boise Art Museum — followed one year later in a tradition that carries on to date. Today, the museum can boast the largest body of Castle work in a public collection, with 97 pieces. While prices for such pieces range in the thousands, Castle was known to exchange them for cigarettes. “At various times, he traded people for a drawing; he liked to smoke,” says Sandy Harthorn, curator of art at the Boise Art Museum.

Like Arion in ancient times, whose skill at the harp freed him from the ill-intention that threatened to entrap him, Castle’s art is the antidote to the snares of irony and cynicism that characterize modernity. Through enchanted renderings, cardboard constructions and charming mini-books, Castle finds the poetic in the prosaic. It is an ever-renewing source of inspiration that unearths a castle in an outbuilding, fashions a kingdom from a hard-scratch farm and plays with patterns like a musician with notes. That is why those who have studied his life and work extensively echo each other when they describe their experience. “The more you do, the more there is to do; when you think you are nearing the end of the task, you find you are almost back at the beginning,” says the Philadelphia Art Museum’s Ann Percy, the curator of drawings who is organizing the Castle exhibition.

From documentarian Wolf: “What I love about this guy in particular is he’s a box of surprises: Every time you get into one box, there are two behind it.” And the Boise Art Museum’s Harthorn: “I have looked at the work for a long time … and I am always discovering something new.”

- “Untitled (two sided drawing)” | Found paper, soot | 3 5/8 x 5 7/8 inches

- “Untitled” | Found paper, color of an unknown origin, soot | 3 1/2 x 7 inches

- “Untitled” | Found paper, soot | 5 3/8 x 11 5/8 inches

- James in Boise, Idaho, in 1950. (Photograph taken by Castle’s nephew, Bob Beach.)

- “Untitled” | Found paper, string, flour paste, soot | 6 1/4 x 2 1/4 inches

No Comments