01 Aug Glass as Consequence

GLASS IS FUSED SILICA (SAND). TRANSPARENT, TRANSLUCENT, voluptuous, fissiparous, it is the ultimate vessel for light — beautiful — with an inherent capacity to self-destruct. In May of 1968 a frizzy-haired American with a Master of Fine Arts in ceramics from the Rhode Island School of Design, showed up on the island of Murano near the floating city of Venice, Italy. Since the 13th century the tiny island has been the glass-blowing capital of the world and, in what was to be an unprecedented apprenticeship, the young man was about to become the first American glassblower to work in the venerable Venini glass factory.

There are other seminal moments. A kibbutz in the Negev Desert in Israel, from which he returned, “determined to make a contribution to the world.” There was Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine, and then the Pilchuck Glass School which he co-founded on the opposite side of the continent. These were the heady, hearty, experimental times where teamwork — the lesson learned in Italy — embedded itself in his ethic. There would be the car accident in England in 1976, robbing him of his left eye and depth perception, and later the shoulder injury, stealing his ability to blow glass. Such accidents, as they so often do, have their antipodal blessings, and he found he could have more, not less, control over his art by directing others.

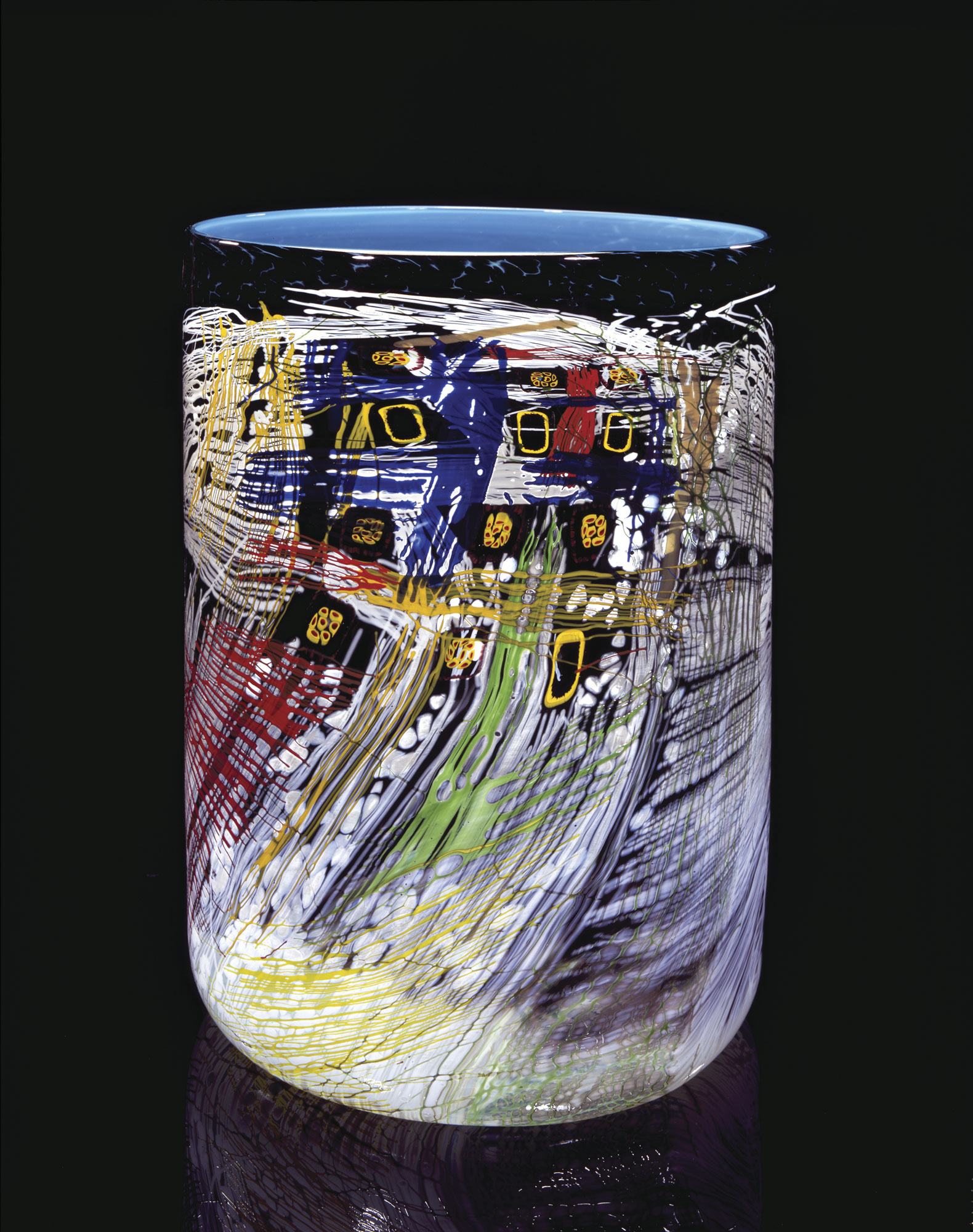

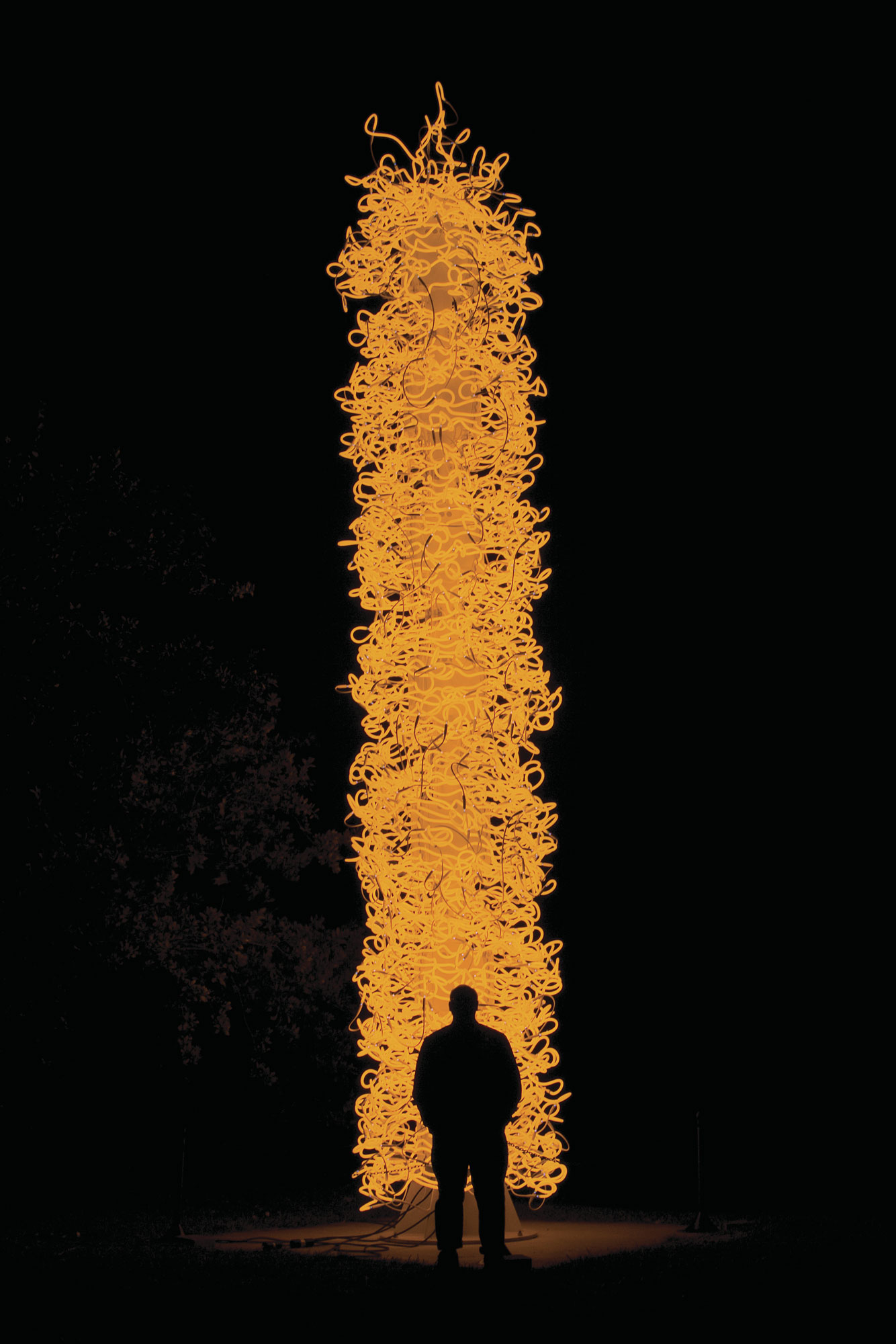

Seattle glass artist Dale Chihuly “creates his own weather,” one journalist quips. What Chihuly precipitates is a deluge of shapes, forms and colors — organic, telluric, kaleidoscopic. Think Dr. Seuss in the garden on acid. Think Matisse meets Pollack meets Christo meets Warhol. There are the famously Slumped Baskets, petted by gravity; and the monstrous chandeliers, giant crystalline constructions weighing up to 2,500 pounds with hundreds of individual glass elements twisting and turning, reminiscent of the tangled hair of Medusa. There are his enormous Floats, glass orbs blown as large as beach balls and technically the most difficult of his creations; not to mention the seductive and biomorphic Sea Forms; or the Ikebana Series, arranging themselves like Technicolor mega-fauna out of the Venetian Series, vases of exuberant if not improbable beauty.

Chihuly’s work has flowered and flowed into more than 200 museums and collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Palais du Louvre and the Corning Museum of Glass. He has also exhibited in the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, the National Gallery of Australia, the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. His work can fetch millions and his fans number as many. Today, anywhere in the world, to say Chihuly is to say blown glass is to say brilliance.

On the day that we meet I am only an hour and a half late for my scheduled interview with His Brilliance. I arrive dry-mouthed at the Ballard Studio in Seattle where the publishing and administrative arms of Chihuly Inc. are located, as well as the mock-up stations where the commissioned artworks and exhibits are assembled. I ask his assistant and publicist, Janet Makela, for water, prayers of indulgence and if the great one will be angered. The answers are yes, yes and no. Minutes later when Chihuly enters the tiny conference room where I wait, he is wearing an electric blue shirt and black slacks. With his corkscrew hair (graying now at 66), black eye-patch (the accident) and paint-splattered shoes (occupational hazard), he sits across from me, a blend of Captain Hook and a giant Panda. When he speaks, his voice is a deep, corrugated rumble, like loose aggregate left in a cement mixer.

Chihuly calls himself an explorer, searching for new ways to use glass. For centuries, especially here in America, glass has traditionally been viewed as a convenience for flowers, something you look through, a good way to carry your gin and tonic. Hamstrung by the practical, confined to the pedestal, it was seen as a kind of high-end craft, something more than your grandmother’s crocheted potholders, but less than fine art. It was Chihuly who freed glass to scale art gallery walls, cross ceilings, be planted in gardens and floated on ponds. He pioneered site-specific large-scale installations, both indoors and out; in the process raising the specter of glass blowing from a craft to an art. Critics can disagree about many aspects of Chihuly’s work, but on one thing they are united. In modern art, before Chihuly, glass carried wine. After Chihuly, it carried consequence.

Team Chihuly, as his empire is known (and currently pegged at 103 employees), churns out thousands of pieces of glass sculptures a year that the maestro has envisioned, drawn, but does not necessarily “create” in the hands-on sense of the word. This, along with his brazen self-promotion and fantastical fame, has earned him his share of detractors. From one end of the blow pipe to the other, Chihuly is commonly raked over the shards, called a glass celebrity (the implication being that he is not an artist) and the Liberace of the art world (in fairness, I saw no feather boas). One coffee-shop owner in Tacoma, Washington, stationed across from the Chihuly Bridge of Glass shrugs at the accusations, likening Chihuly to Elvis: “He did for blown glass what Elvis did for rock and roll.”

Chihuly has indeed achieved a rock star-type status, but does not consider himself a genius. “No, I wouldn’t use that word myself,” I was told. Instead he sees himself as a movie director or a ship’s captain, someone who inspires and orchestrates. “One of the most important things is to work with a team of people,” he told me. “No more than Frank Lloyd Wright could have had a career and built 600 buildings, or whatever he built, I couldn’t have done anything like what I’ve done if I didn’t have a lot of people working for me. To blow glass you really have to have the ability to be inspirational to the team. Hardly anybody blows glass alone.”

The idea of teamwork is fundamental for Chihuly. It is part of his being. But there must also be inspiration, the ideas his team can work from. “Maybe they [the ideas] are the single most important thing,” Chihuly said when I posited this to him. “But you have to have the team. Maybe it is a chicken-and-egg kind of thing. Which really does come first? When I think back about when I first started, I started blowing glass alone in graduate school, but it wasn’t very long before I started getting people to help me. Then when I went to Italy for a year I got to see the teams working together in Venini. There wasn’t any doubt in my mind that it had to be done with a team.”

“I think more from my gut than my head,” is a phrase Chihuly often repeats. “I like to work fast. The work will turn out better with speed. The initial force and idea comes through when you work in a fast way.” To communicate his ideas, Chihuly works much like Pollack (an artist he admires), spreading a sheet of paper on the floor and standing over it, squeezing and squirting paint directly from the tubes. He does not appear to think, but spontaneously creates sweeping calligraphic arabesques and employs great daubs and puddles of color at will. From these the gaffers blow and spin and heat and create, often with rock music thudding in the background. In his introduction to Ecstasies of the Mind and Senses, a coffee-table book put out by Chihuly’s publishing company, Portland Press, Jack Cobert writes about Chihuly’s flamboyant style of painting: “Chihuly’s large, broadly gestural, high-dynamic color-painted drawings start the process. These energetic renderings are his way of showing the glass teams, succinctly and provocatively, what he has in mind. Not mechanical blueprints, they are rough two-dimensional versions of hoped-for three-dimensional creations.”

Standing in front of one of Chihuly’s actualized three-dimensional creations is to be captured by a spell. Hot colors are frozen in balletic gestures. Light is trapped, bent, amplified and released in an afflatus of beauty. There is a hallucinogenic quality to his work, a dazzling array of shapes and colors bombarding the pleasure centers of the brain. Much of Chihuly’s work suggests the surrealistic floral paintings of Joseph Stella. Asked about influences and favorite artists, Chihuly mentions Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Pollack, as well as Americans Jeff Koons and Kiki Smith.

Museums, by and large, are quiet, seemingly dead places — tombs of whispers and catacombs of heels clicking across polished floors. A visit to a Chihuly exhibit is different. Gasps of surprise and delight are common. People drag each other by the sleeve to a favorite piece. Hands fly to mouths and eyes open wide. The single most heard expression is, “Oh my God.” The single most uttered word, “Wow.”

Chihuly’s work is wow. It’s main function, delight. One critic accounts for this by saying Chihuly “exploits the spontaneity of the glass-blowing medium and embraces it rather than trying to subjugate it to his will.” One of the best examples of this is his Slumped Basket Series. In 1977 while visiting the Tacoma Historical Society, Chihuly was shown a storeroom where Native American baskets were heaped and nestled together, the slumped forms sagging under their own weight much as molten glass does when being blown. “I wanted to capture this in glass,” Chihuly said. “The breakthrough for me was recognizing that heat and gravity were the tools to be used to make these forms.”

At one point during my visit, I was invited to sit in on a meeting about the exhibit Chihuly is in the process of designing for the De Young Museum in San Francisco. Around a large table on the second floor of the Ballard studios, I was surrounded by examples of Chihuly’s glasswork spanning his entire career, including new work. In addition, there were at least three of his newest paintings. Over the last year, Chihuly has experimented with painting on canvas (not the usual art paper he uses), but in this case the paintings are not meant as diagrams for the gaffers to work from, but created as works of art in their own right.

Chihuly sat at the head of the table studying floor plans of the museum. With a black Sharpie he moved walls and adjusted shelf heights. Just before the meeting Chihuly told me this is what he loves to do, planning how his work will be seen. “Probably what gives me the biggest thrill,” he said, “is planning an exhibition. I’m more interested what the room or what the exhibition will look like than the actual single object. That’s different than years ago when I did more single objects, but even then, I often thought of them being together in an exhibition. If I had 25 cylinders I thought about what kind of shelves they’d be on, what kind of light I’d put on them. I used to need to make my own light fixtures. Back 30 years ago they didn’t have the sort of spotlights like now. So I’d make cones which allowed the room to be fairly dark but the object fairly light, and now that’s the way most people do shows.”

One of the highlights of the De Young exhibit will be recreating his Glass Forest installation from 1971, a series of nine-foot-high white “trees” owned by the Museum Bellerive in Zurich, Switzerland. “It’s fairly fragile,” Chihuly says, “more so than most of my work. I’d like to have them send it, and they agreed to lend it, but I’m not sure. It might break traveling over or traveling back and [I] didn’t want to take that chance. So I decided I’m going make it over, but I’m not going to make it exactly like it was. I want it to be a new piece but in the spirit of 1971.” Then he added, “But once I get going, it might take a different direction.”

Around the perimeter of the room was a set of low display cases that open to reveal a variety of his glass work. Black is a color Chihuly hasn’t often used, and a set of black nested bowls was displayed among them. There is a sleek elegance to these new pieces, a graceful formality suggesting the Orient and the wonderful black lacquers of Japan. They stand out from his more flamboyant work, the intrepid Macchia (meaning spotted in Italian) and the sometimes dinosauric Venetians, vases laced with paprika, larkspur and the rubies he often uses. “I’ve never met a color I didn’t like,” Chihuly is famous for saying. He works from a color palette of more than 300 glass rods, but the recent simple black work is beautiful, and he knows it is strong.

“I’m going back and doing four or five of the series in black,” he says. “It’s kind of fun to see what these series would look like in black. I’ve never done them in black, it’s not a color I usually use. I definitely want to show the black baskets because that’s very new work and there’s no doubt in my mind they’re really good.”

Then, almost in the next breath, “We’re also working on a new piece right now, a proposal for Dubai, and it’s all white. Proposing it for that new building [the Bhurj Dubai] that’s going to be the tallest in the world. It will be a new shape and new color and we’ve never done any major works in white. And it’s not just white, it’s translucent and it’s clear, it’s all those things together. When light goes through it there’s almost a little pink in it.”

Chihuly has always said, “I want my work to look like it just happened, as if it was made by nature.” For four decades his fantastical shapes, colors and inventiveness have reached across the medium as if to turn up the volume on nature. With faith in the ineffable, and employing teams of professionals, he has propelled himself and the art of glass onto the national and international scene. As a boy walking the beaches of his hometown of Tacoma, Washington, he could not have predicted this. But he remembers being hypnotized by the sensual forms nature so blithely produces, and they would stick with him, as would visions of his mother’s flower garden and the stained glass windows of churches. Then, one day in graduate school, in a basement apartment with a makeshift kiln and piece of pipe, all would join forces as he blew his first improbable bubble of glass.

“People ask me why I work with glass,” he says, “and how I got started. I never really know the answer why, because I don’t start with reason. I began from a fascination of glass itself.”

- “Persian Chandelier”, 2007, 94 x 118 x 112 inches, Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- “Black Basket Set with Orange Lip Wraps”, 2006, 12 x 21 x 20 inches.

- “Blue Herons, Walla Wallas, and Reichenback Mirrored Balls”, 2006, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York.

- “Ming Green Black Macchia with Tangerine Lip Wrap”, 2007, 22 x 33 x 39 inches

- “Blue Appeal Seaform Set with Astral White Lip Wraps”, 2003, 11 x 23 x 20 inches.

- Dale Chihuly drawing on the Boathouse deck, Seattle, Washington.

- “Black Cylinder #18”, 2006, 16 x 12 x 12 inches.

- “Saffron Neon Tower”, 2006, 324 x 60 x 60 inches, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Coral Gables, Florida.

- “Neodymium Spears”, 2000, Kleifarvatn, Iceland.

No Comments