06 Sep Here, Now and Always

This past summer, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC) reopened its seminal exhibition, Here, Now and Always. More than 1,100 objects were uninstalled to give way to a new, re-envisioned museum experience that will once again become the standard for how museums relate and collaborate with Indigenous communities.

The completion of the new iteration of Here, Now and Always was the last contribution to the institution by Della Warrior, the executive director of MIAC from 2013 to 2021. “I am proud to have been a part of updating the story to reflect how these Indigenous peoples lived, learned, accomplished, and faced life’s evolutions and challenges,” says Warrior. “Over 60 Native advisers worked with the curator to conceptualize each thematic area and incorporate art and artifacts that reflect key historical and cultural changes.”

The Warrior, a ring by artist Ken Romero (Taos Pueblo/Laguna Pueblo), is a rich collage of turquoise stones.

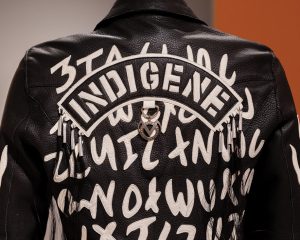

Indigene Script Jacket by artist Virgil Ortiz (Cochiti Pueblo) is an example from Ortiz’s fashion line, Indigene. His futuristic designs include his “Rez Spine” leather accessories, silk scarves, and a selection of edgy leather jackets, among other articles of clothing.

A tufa-cast cuff by artist Darryl Dean Begay (Navajo) shows the rich texture achieved by this traditional method of jewelry making.

The re-envisioning of Here, Now and Always began nearly eight years ago and reopened to the public in July 2022. The exhibition is housed within the museum’s 8,400-square-foot Amy Rose Bloch Wing and features more than 600 objects from the permanent collection, including works by contemporary artists Mateo Romero, Jason Garcia, Diego Romero, Shonto Begay, Connie Gaussoin, and the team of Lisa Holt and Harlan Reano.

These moccasins are from Taos Pueblo, circa 1925.

This Puerco black-on-white bowl is from New Mexico and was made between 1100 and 1150 A.D.

A small carved stone animal, or fetish, from Zuni Pueblo, circa 1930.

For Warrior, the update assists in setting a new framework for curators working with Indigenous populations and brings the true history of the Southwest to a broader audience. “It is my hope that through educating the public about the great cultures of these people, preconceived notions that emanate from stereotypes and perceptions derived from inaccurate or one-sided histories will change. It is my hope that the unique and valuable cultures of the Indigenous peoples of the Southwest are better understood and appreciated for all that they contribute to the world,” Warrior says.

A jar by Randy Nahohai (Zuni Pueblo), who learned how to make pottery from his mother.

Beaded High-Tops by artist Terri Greeves (Kiowa) offer a contemporary perspective on traditional crafts.

The geometric designs on this water jar by artist Teofila Torivio (Acoma Pueblo) are hand-painted.

Here, Now and Always opened as MIAC’s first exhibition in 1997. It was also the first exhibit in the Southwest that foregrounded the voices of Indigenous people in this region. “Instead of the idea of museums explaining indigeneity to non-Natives, this was the first exhibition that had Native curators speaking for themselves, telling their own stories. And that was very revolutionary for a museum at that time,” says Lillia McEnaney, assistant curator at MIAC.

Jason Garcia (Okuu Pín) (Santa Clara Pueblo) | Zuni Olla Maiden | Ceramic Tile

The exhibition is broken up into seven categories: ancestors; cycles; community and home; trade and exchange; arts; language and song; and survival and resilience. While the themes of the exhibition remain largely intact from their original iterations 25 years ago, the curators decided to add a new category, community. “What we did was combine ‘home’ and ‘plants and animals’ into [the] ‘community [and home’ category], as a result of discussions with curators and thinking of the two more holistically,” says Antonio Chavarria, Curator of Ethnology for MIAC.

Allan Houser | Chiricahua Apache), Apache Ghan Dancers | Tempera on Paper | 1934

Some of the works in the new exhibition were commissioned, such as a dress designed by Loren Aragon, a fashion designer from Acoma Pueblo whose work is inspired by his pueblo’s pottery and culture. The dress Ancestral Awakening was inspired by an Acoma pot in MIAC’s permanent collection.

The collection at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture includes historical and contemporary works by Native American artists, including a pair of Mescalero Apache moccasins made for a young girl

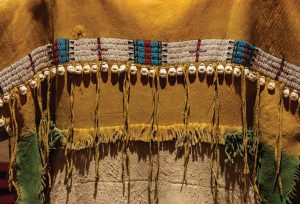

A dress made by a member of the Muache Ute or Capote Ute tribe in the early 1900s

“This is important because one of the roles of a museum is to make the collection accessible to Native artists, and when you look at Loren’s dress and the pot that inspired it, it is just incredible to see those connections. Collections are not always accessible to the public historically, so it is important that our collections are available to Native communities,” says Chavarria.

An early example of a Navajo doll

A painting from the Deer Dancer series by contemporary artist Mateo Romero (Cochiti Pueblo)

Fashion was not part of the original Here, Now and Always exhibition either. Its inclusion displays how vital fashion is to Native art right now, and how conceptions of “Native art” are always evolving and changing. Couture by designers Virgil Ortiz, Patricia Michaels, and Teri Greeves is included in the new exhibit.

A ceramic jar by Diego Romero (Cochiti Pueblo)

Another highlight from the exhibition is Marla Allison’s large triptych in the museum’s survival and resilience category, Water Girls. Painted in bold black and red, Allison has depicted two figures representing her heritage — Laguna and Hopi. The figures were references from Edward Curtis photographs. Allison superimposed Laguna and Hopi designs over the figurative elements of the painting.

Vignettes of a Pueblo home circa 1944

A trading post

Another interesting object in the collection is the traditional Pueblo dress that U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland wore at her swearing-in ceremony for the U.S. House of Representatives in 2019. She was one of the first two Indigenous women to serve in Congress, and, in 2021, she became the first Indigenous person to be part of a presidential cabinet.

A tipi

The dress (bottom left) was designed by Loren Aragon (Acoma Pueblo) and represents the importance of fashion in some Native American cultures today.

“I am happy with how the exhibition came out,” says Chavarria. “It looks stunning. The videos add a lot of depth and context. Overall, it is a great showcase of the Native cultures of the Southwest. We hope it provides inspiration to people to learn more and appreciate the work of Native artists of today and yesterday and see that art is just one aspect of culture.”

No Comments