01 Sep Hidden Grace

IT'S 5:45 IN THE MORNING when artist September Vhay and I drive north up Jackson Hole to the Triangle X Guest Ranch, where she will photograph a herd of grays, sorrels, bays, paints, palominos, black and white horses as they are wrangled from the river bottom across Highway 89 to the ranch. Dawn brightens the eastern sky, and Vhay, a painter, suggests a combination of Aurelian and Rose Madder pigments to depict the glow.

We get to the roadside too early, but warm up photographing a fog bank rising off the Snake River as the Tetons turn pink. Vhay’s dachshund puppy, Uma, rides in a backpack for fear of being left unattended; and passing tourists stop, camera ready, assuming we’ve spotted a moose. Eventually the horses arrive and Vhay, a svelte native of Reno, Nevada, with bright blue eyes, springs into action. One horse has caught her attention: a white Arabian mare that virtually dances.

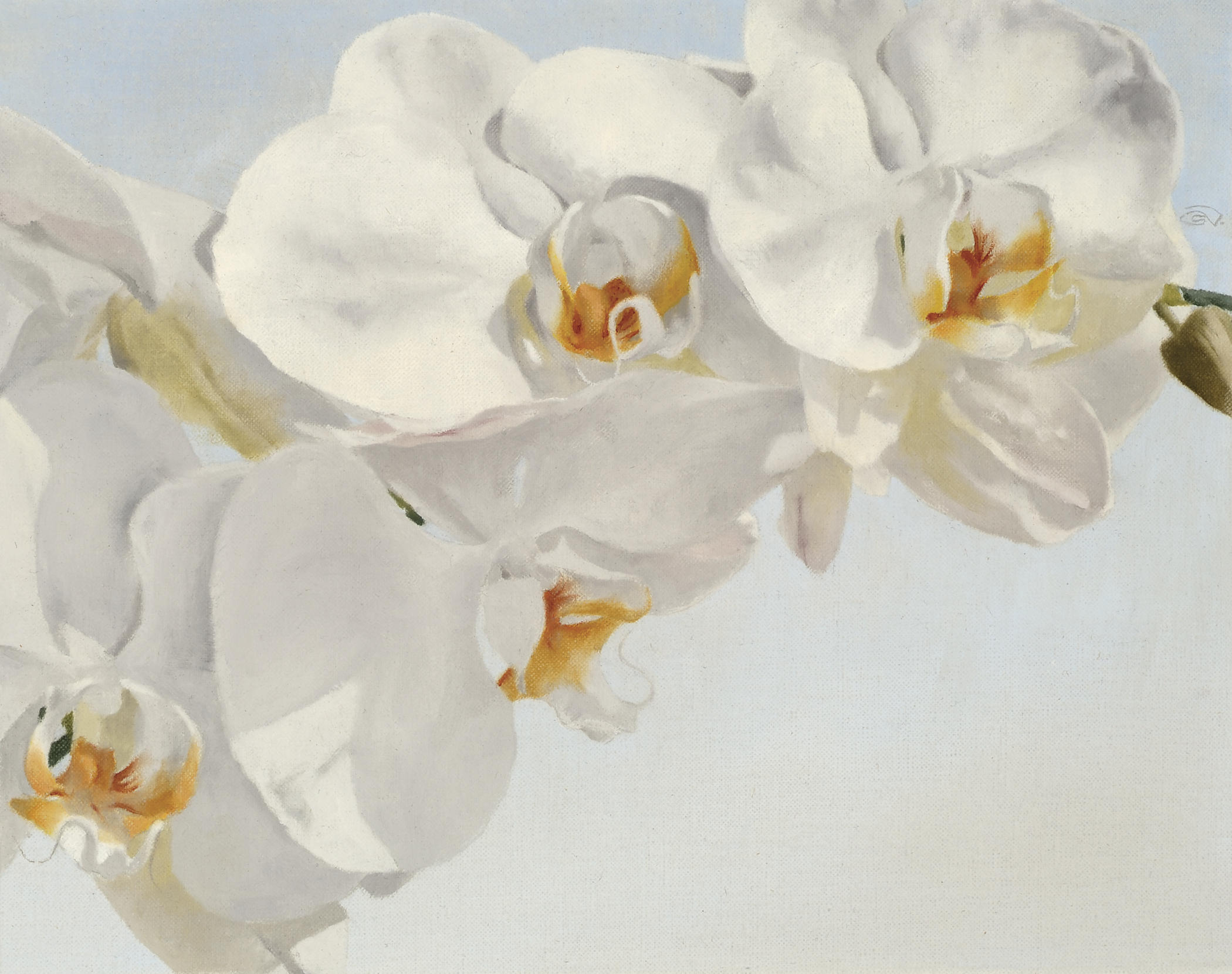

Vhay enjoys painting horses, white horses in particular, and these photographs, in consort with journal sketches, may lead to a painting. Although she’s known for her favorite subject she is not strictly an equine painter. Ravens, a mountain goat and white orchids also adorned the walls of her last show, and though her subjects are natural, she is not limited to wildlife. As one of her mentors, oil painter Scott Christensen, says, “September paints for herself as much as anybody. The subject is second.” Lauded by patrons and highly regarded by her peers, Vhay is an artist’s artist, dedicated fully to her muse, her medium and the lifestyle they make possible.

On a similar morning 10 years ago, Vhay skipped out on work to photograph 200 horses being herded through Buffalo Valley. That’s when she decided to end her career in architecture. Tired of sitting in an office, a slave to long hours, she had become haunted by scenes that piqued her artistic eye, glimpses she felt compelled to depict. She calls them “clarity moments,” and they are the geneses of paintings. Already adept at drawing and masterful with watercolor technique — having spent years doing architectural renderings — Vhay quit her job to paint full-time. “I have more to say with painting,” she affirms.

Such transitions are never easy, of course, but Vhay has art as well as architecture in her blood. Although her father is an architect, as was his father (who also did watercolors) and grandmother, Vhay’s paternal grandmother, Mary Ellis Borglum, encouraged her to paint. She was the daughter of Gutzon Borglum, who designed Mount Rushmore. “As a child I spent hours looking at his paintings and sculptures,” Vhay reflects as she describes a particularly mesmerizing Borglum oil that hung in her grandmother’s home. “It was a dark horse, a cowboy’s horse at night,” she says. “Like a ghost looking at the camp fire.”

Vhay’s other early muse was the Scottish designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh. At 23, while studying architecture at University of Oregon, she spent a summer on scholarship in Scotland sketching and painting Mackintosh’s buildings. She became obsessed. “I realized that nature is compositionally perfect and that Mackintosh was inspired by nature,” Vhay explains. “That brought me straight to the source.” It has paid off. Vhay is now represented by Maria Hajic, Director of Naturalism at Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Valuing simplicity and leaving copious empty space, which, she explains, gives your eye a place to rest, Vhay’s compositions are strong and deliberately cropped. “I see things in a minimal, clear way because of my architecture training,” she says. Vhay’s talent is recognized by her friend and mentor, oil painter John Felsing. “The horse was off to one corner … very captivating,” muses Felsing, referring to a painting he saw in her studio. “It made me want to finish it in my mind.”

Vhay’s work is as much about what is not there, what is unsaid, as what is there, and more about the overall design than the subject. “I’m very deliberate about that edge,” she says, pointing to a close-cropped mountain goat oil, Winter’s Harmony, hanging in the Jackson, Wyoming gallery, Trio, that she co-owns. She believes the patterns of negative space between the horns add drama. “It creates interesting shapes,” says Vhay. “It’s less literal.” Christensen sees the same effect in two pieces he owns. “It’s all about the negative shapes,” he declares. “Which make a very solid abstract design.”

Because of her watercolor background, Vhay thinks a lot about white, which, in watercolor, is not paint, but the white of the paper. “Compositionally your eyes are drawn to the whites first,” says Vhay, who will do a study of whites to understand their pattern before she begins to paint. “With watercolor you have to be deliberate, planning a painting before you do it, because it’s so fragile you can ruin it quickly,” she explains. For the past five years she has been applying this watercolor technique to a less familiar medium — oil.

Unlike watercolor, oil can be abused, wiped away and painted over. This give and take, which Felsing calls “beautiful destruction,” is fun for Vhay and she enthusiastically points out examples of the process. “It’s that dialogue with the painting that I’m really enjoying,” she explains. “You put paint on and lift it off.” Painting in thin layers, Vhay rarely reworks a composition, which makes her oils fresh. “This paint is barely covering the linen,” she says of a 30-by-60-inch depiction of a horse called Dreams of Midnight. With this combination of planning and improvisation, watercolor technique combined with oil technique, Vhay has created her own style.

Vhay’s willingness to experiment was clearly evident in her recent one-woman show, Alacrity. Also the title of a white colt in oil, the collection illustrated her range and agility. Among her horse paintings were three versions of Nora’s Gait, a Conté sketch plus a tonal oil that had originally been the understudy for a larger oil that was also exhibited, unfinished. All sold. Among other paintings were three oils of white orchids, entitled Ode to O’Keeffe One, Two, and Three, that took viewers’ breath away with their elegant oriental style and close color values. Three-quarters of the show sold.

Of Alacrity, Vhay says, “I almost feel like I channeled that painting.” Yet she did the hard work ahead of time, first photographing the beguiling youngster, who is a registered paint horse but, oddly, solid white; then doing studies in charcoal, watercolor and oil. “I knew the imagery so well,” she adds, “it freed my ability.” It is obvious. The essence of the colt’s form is captured on canvas. “When you get proficient with a medium, freedom evolves,” says Felsing, who likes to paraphrase jazz musician Charlie Parker. “First you master the instrument,” he says. “Then you master the music. Then you forget all that shit and just play.”

Vhay is playing loud and clear. She has been repeatedly invited to eminent exhibits: Woodson Art Museum’s Birds in Art, the American Academy of Equine Art’s annual juried exhibit and the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s Western Visions: Miniatures and More, where last year she was honored with the Trustee’s Purchase Award for a painting of a chickadee, now in the museum’s permanent collection.

The 43-year-old’s talents are seemingly limitless, as is her curiosity. As we sit in Lotus Café over breakfast on our return from the ranch, she talks excitedly about painting a huge red begonia. “You know, red!” she says smiling. Vhay brings the same enthusiasm, deliberation and light touch to all her paintings, which, in the words of Hajic, “use light and shadow to emphasize the hidden grace of her subjects.” It would be no surprise if someday Vhay followed in Borglum’s footsteps and found the hidden grace in stone.

Working as a freelance writer and documentary filmmaker, Wilson, Wyoming native, Seonaid B. Campbell explores her passion for the arts and life science. She lives with her beau and their dog in Livingston, which she affectionately calls the east village of Montana. Her Gaelic name, pronounced “Shona,” comes from her family in Argyll, Scotland; so does her taste for single malts.

- “Dreams of Midnight” | Oil on Belgian Linen | 30 x 60 inches | 2011

- “Winter’s Harmony” | Oil on Linen | 18 x 36 inches | 2011

- Vhay, with puppy Uma on her back, stands before the Tetons. Photo: Seonaid B. Campbell

- “Meadow Fox” | Watercolor on Paper | 10 x 20 inches | 2009

- “Ode to O’Keeffe” | Oil on Belgian Linen | 10 x 13 inches | 2011

- “Alacrity” | Oil on Linen | 12 x 24 inches | 2011

No Comments