14 May History's Palette

TELEVISION TODAY BRINGS US ONE SERIES AFTER ANOTHER featuring forensic scientists solving crimes. But forensic science also plays an important role in solving mysteries in the art world. It can expose forgeries and reveal the fascinating methods of ancient masters and the rare and unusual pigments they used.

An art materials repository, the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies is part of Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum. Founded in 1928, the Straus Center is the oldest fine arts conservation treatment, research and training facility in the United States. Its director, Narayan Khandekar, oversees the activities of the center’s four labs (paintings, objects, works on paper and analytical) and a staff of scientists, post-doctoral students and artists. He is also the senior conservation scientist in the center’s analytical lab and the current caretaker of the center’s materials collection, which includes the renowned Forbes Pigment Collection and the Gettens Collection of Binding Media and Varnishes. For any art lover, the center shelters a treasure trove of delights.

The pigment collection was founded in the early 20th century by Edward Waldo Forbes, director of the Fogg Art Museum from 1909 to 1944. Forbes was fascinated with how specific mediums could provide clues to a painting’s authenticity. He was an avid traveler, and by the 1920s, he had gathered pigment samples in a rainbow of colors, a bright array of hues and substances. As awareness of his interest grew, so did donations, and the museum’s collection now comprises more than 2,500 samples.

Today, Khandekar and his team use techniques such as Raman spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, gas chromatography and electron microscopy to determine the chemical composition of different art materials used throughout history. They take tiny samples from artworks to authenticate mediums, answer historical questions and to verify origins. Recognized and respected worldwide, the Straus Center sends samples to museums and laboratories to help art experts across the globe.

In earlier centuries, before distributors provided hundreds of colors in ready-mix tube, artists had to grind and mix ingredients, blending them with binding mediums through an intensive trial-and-error process. Often these formulas were passed from one craftsman to another and held in secret like a favorite family recipe for generations. They also engendered lively public speculation.

Some ingredients were rare, costly and required skillful processing. For example, the vivid blue in the Virgin’s mantle in Sandro Botticelli’s The Virgin and Child (c. 1490) contains ground lapis lazuli, a stone mined in Afghanistan. To use it in a painting demanded that the artist carefully grind the mineral into fine particles. Highly sought in medieval times, Khandekar says this color was often “more prized than gold.”

Each sample in the Straus collection carries with it a history of discovery and a story about its original era of use. Analyzing them is like searching the limbs of a family tree to establish ancestry. Some of the most unusual pigments include toxic ingredients, rare metals, insect extracts and even human remains.

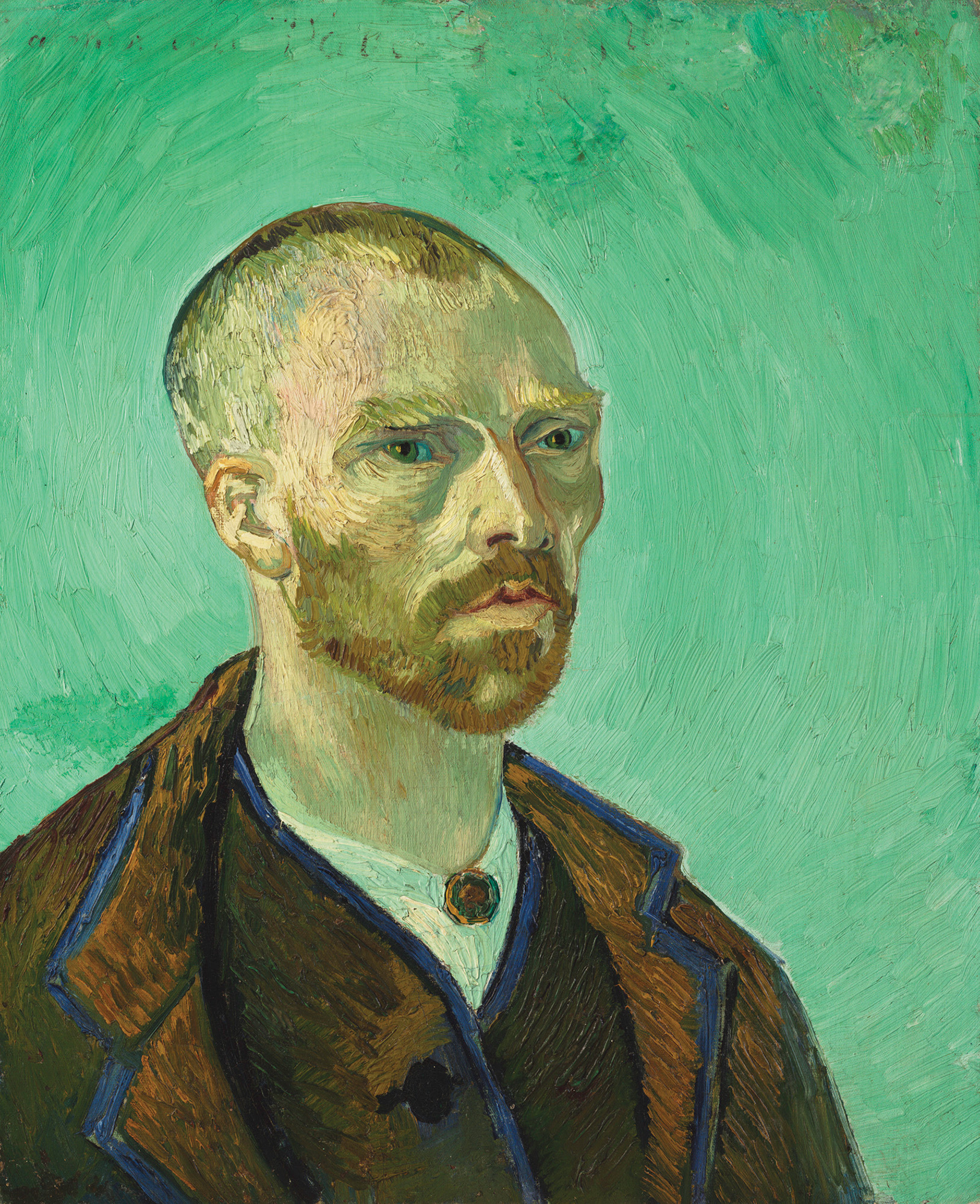

For instance, copper acetoarsenite, a deep, lush green that can be seen in the background of Vincent van Gogh’s Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin (1888), contains arsenic, is very poisonous and was also used at one time as an insecticide. Another rare and expensive ingredient, known as Tyrian purple, comes from a secretion of a sea snail. Considered a status symbol, Byzantine emperors designated it “royal purple,” and its use was forbidden for anyone outside the imperial court.

In a recent article for National Geographic, Kristin Romey wrote about European artists who used pigments made from the “pulverized remains of ancient Egyptians.” Hard to imagine, but from approximately the 16th century through the early 1900s “Mummy Brown,” derived from Egyptian mummies, was prized for its “rich, transparent shade,” although not all artists may have been aware of its source. Tubes of brown pigment called “Mummy” are still available today but without the notorious ingredient.

But all is not history in the world of paint. In a more modern coup, the Straus Center was able to prove a rediscovered Jackson Pollock painting was a fake. Pigment analysis confirmed that a red used in it, Red 254, was not even manufactured until about 30 years after the artist’s death.

Some artists working today still revere historic pigment preparation. Justin Hess, an award-winning San Francisco, California, painter trained in the Classical Realist tradition, has built his reputation on a foundation of knowledge and respect for the entire creative process from concept to finished artwork. Hess spent six years studying and working in Florence, Italy, learning how to make his paints and canvases from scratch. He believes these time-proven techniques “ensure that the beauty of my craft will stand the test of time and contribute to the reawakening of Classical Realist painting.”

Processing and combining naturally occurring minerals with just the right medium and mulling them to Hess’ preferred consistency takes time, but he says the task is as important to the final result as the brushstrokes on his carefully crafted canvases. His luminous Serenade for those who Sacrifice incorporates more than a half-dozen handmade pigments, including the rare lead-tin yellow.

Hess offers ongoing classes in his California atelier as well as workshops around the country. He’s also the author of Controlling the Creative Process: A Painter’s Guide to Methods and Materials, and his paintings are found in private collections in Australia, Europe, Scandinavia and the United States.

The Straus Center’s collection continues to expand, says Khandekar. “We buy about 250 grams of pigments a year, including those presently in use, so that as newer artworks come in for analysis we have a compendium for comparison.” Its collection and investigations include an ever-expanding range of mediums. Recently, the center received samples of the natural dyes prominent Zapotec weaver Porfirio Gutiérrez uses in the textiles he and his family have produced for generations in Oaxaca, Mexico. These dyes are derived from regionally gathered plants, minerals and insects.

The center’s dedication and devotion to uncovering the secrets of the art world help us understand both past and present artistic processes. The journey continues, and we can look forward to even more exciting tales of exotic pigments, deceit revealed and inspiring history as technology advances.

- Samples from the Forbes Pigment Collection. Photos: Peter Vanderwarker and Jenny Stenger (last image)

- Narayan Khandekar, senior conservation scientist and director of the Staus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, looks through the materials collection. Photo: Antoinette Hocbo All images, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

- Vincent van Gogh “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin” | Oil on Canvas | 1888 Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest from the Collection of Maurice Wertheim, Class of 1906

- Samples from the Forbes Pigment Collection. Photos: Peter Vanderwarker and Jenny Stenger (last image)

- Justin Hess | “Serenade for those who Sacrifice” | Oil on Linen | 80 x 72 inches

- Lapis Lazuli was used to create ultramarine pigment found in Botticelli’s The Virgin and Child. Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Forbes Pigment Collection, Straus.542. | All images, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

- Samples from the Forbes Pigment Collection. Photos: Peter Vanderwarker and Jenny Stenger (last image)

- Mummy Brown was originally made from the remains of ancient Egyptians. Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, The Forbes Pigment Collection, Straus.17.

- Samples from the Forbes Pigment Collection. Photos: Peter Vanderwarker and Jenny Stenger (last image)

- Sandro Botticelli, “The Virgin and Child” (detail) | Tempera on Panel | Circa 1490 | Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop

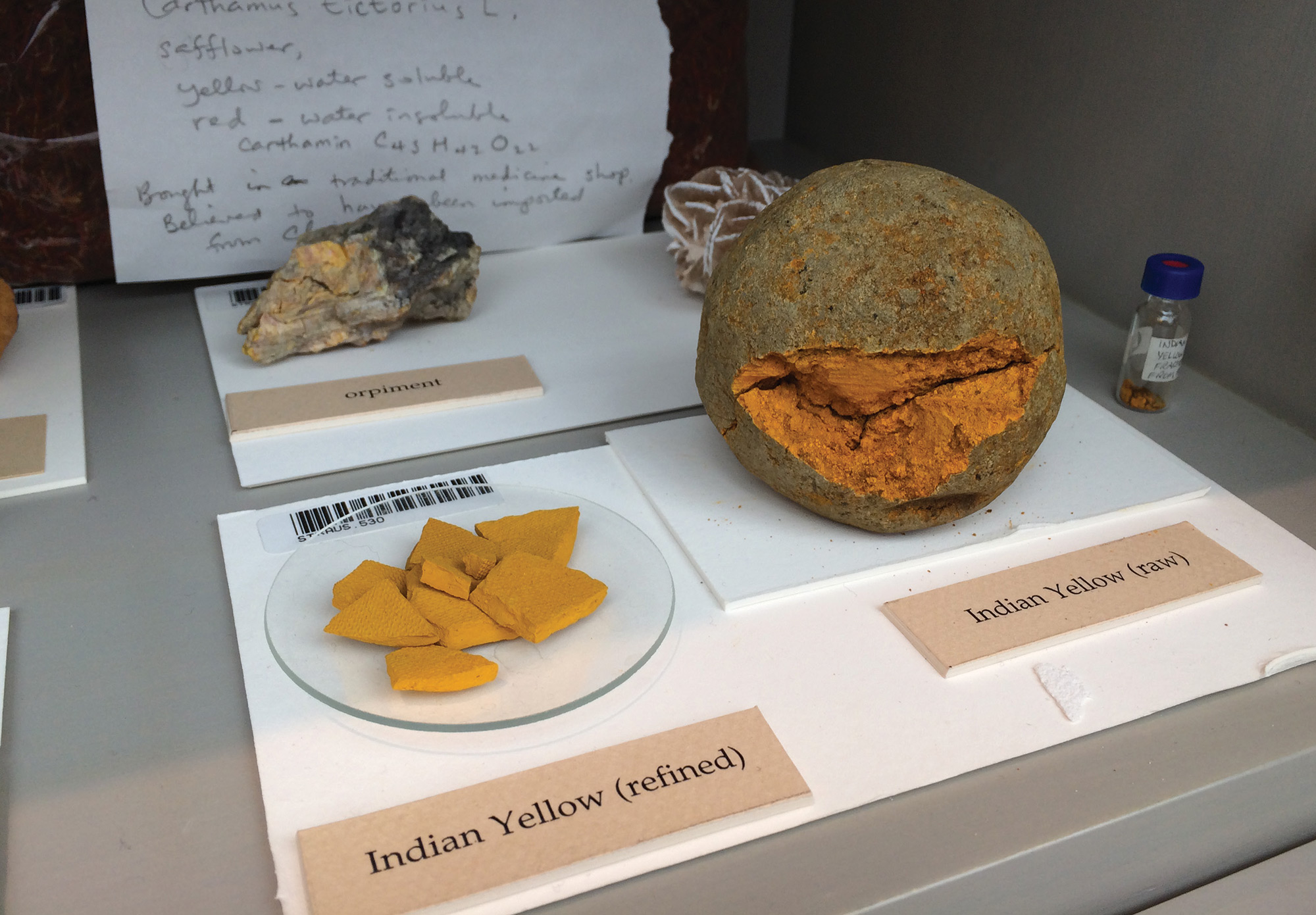

- Samples of Indian Yellow, which was originally made from the urine of cows fed exclusively on mango leaves. Photo: Jenny Stenger. Photos: Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

No Comments