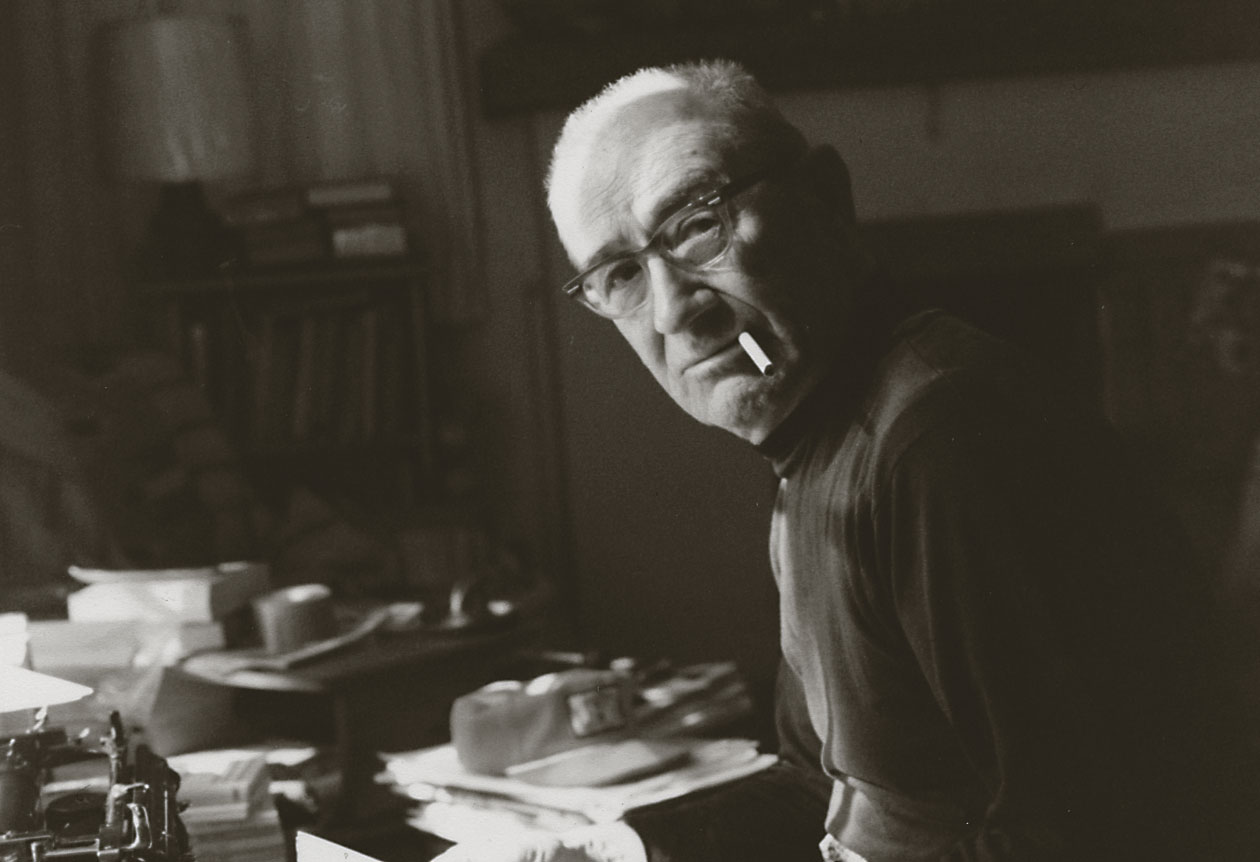

01 Sep Ignatz Sahula-Dycke (1900-1982)

SMOLDERING POLITICAL TENSIONS IN BOHEMIA at the turn of the 20th century ironically gave rise to one of the West’s most impassioned painters of horses, Indians of the Southwest and cowboys. Ignatz Sahula-Dycke captured the actions of men and women that typified the period in the region he loved, but his path to recording the romance and raw beauty of life in the West was filled with switchbacks and open stretches in his own life, and relative obscurity in his career.

Despite his obvious talent, Sahula-Dycke is little known, says Tito Chavez, owner of Tito’s Gallery in Las Vegas, New Mexico, one of the few galleries to carry the artist’s work. “Sahula-Dycke moved numerous times between the commercial art world and painting for his own pleasure, but there’s little evidence that he followed a sustained course to build a career and reputation as a fine artist,” says Chavez. Still, argues Chavez, Sahula-Dycke is an artist worth knowing about.

Born in Scutec, Bohemia, Austria, in 1900, Ignatz Sahula-Dycke was the son of Jan Sahula, a concert violinist, music professor in Prague, landowner and businessman. His mother, Eugenia Dycke, was a painter and a descendant of the early 17th-century Flemish painter Anthony Van Dyck, who was renowned for his portraits of aristocrats and noblemen. As a boy, Sahula-Dycke’s passion was drawing and painting horses.

Horses — how they moved, walked, galloped, played and worked — were subjects of study for Sahula-Dycke, as reflected in such pieces as Springtime Reverie and Protecting Her Own. According to later articles and interviews with the artist, he is credited with having done his first drawing of a horse at age three, and his proximity to them on the family’s farm only fueled his fascination.

When the Sahula family left Europe in 1908 and arrived in Chicago, the boy’s talent was recognized immediately by his elementary school teachers. Only nine years old, Sahula-Dycke won a scholarship to the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts.

Following his graduation, Sahula-Dycke worked briefly for a Chicago advertising agency and joined the Navy, before being discharged in 1919. Whenever possible, he continued to take classes at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts.

Jobs were scarce and Sahula-Dycke was convinced to become a freelance commercial artist while turning out work that he referred to as “acceptable paintings.” It was apparently during this period that he added Dycke to his name to honor his mother and his half brother, Bob Dycke, a well-known artist and sculptor in Dalhart, Texas.

At 21, Sahula-Dycke entered a painting for exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, which continued to accept his work through 1928. During that time, he won a number of prizes, awards and honorable mentions.

For a work entitled The City of Dreadful Night he won the 1925 Robert Rice Jenkins Prize, awarded by the Art Institute of Chicago. He was also a fifth-place winner in an international competition for a Chicago World’s Fair poster.

Sahula-Dycke aimed for striking contrasts within an already established family of tones; he was known to mix every color on his palette before touching brush to canvas. Considered a “modernist” by some in the early years, Sahula-Dycke did not fear experimentation. He worked in oil, encaustic, tempera, crayon, casein and watercolors, and he used paper and canvas board, as well as canvas.

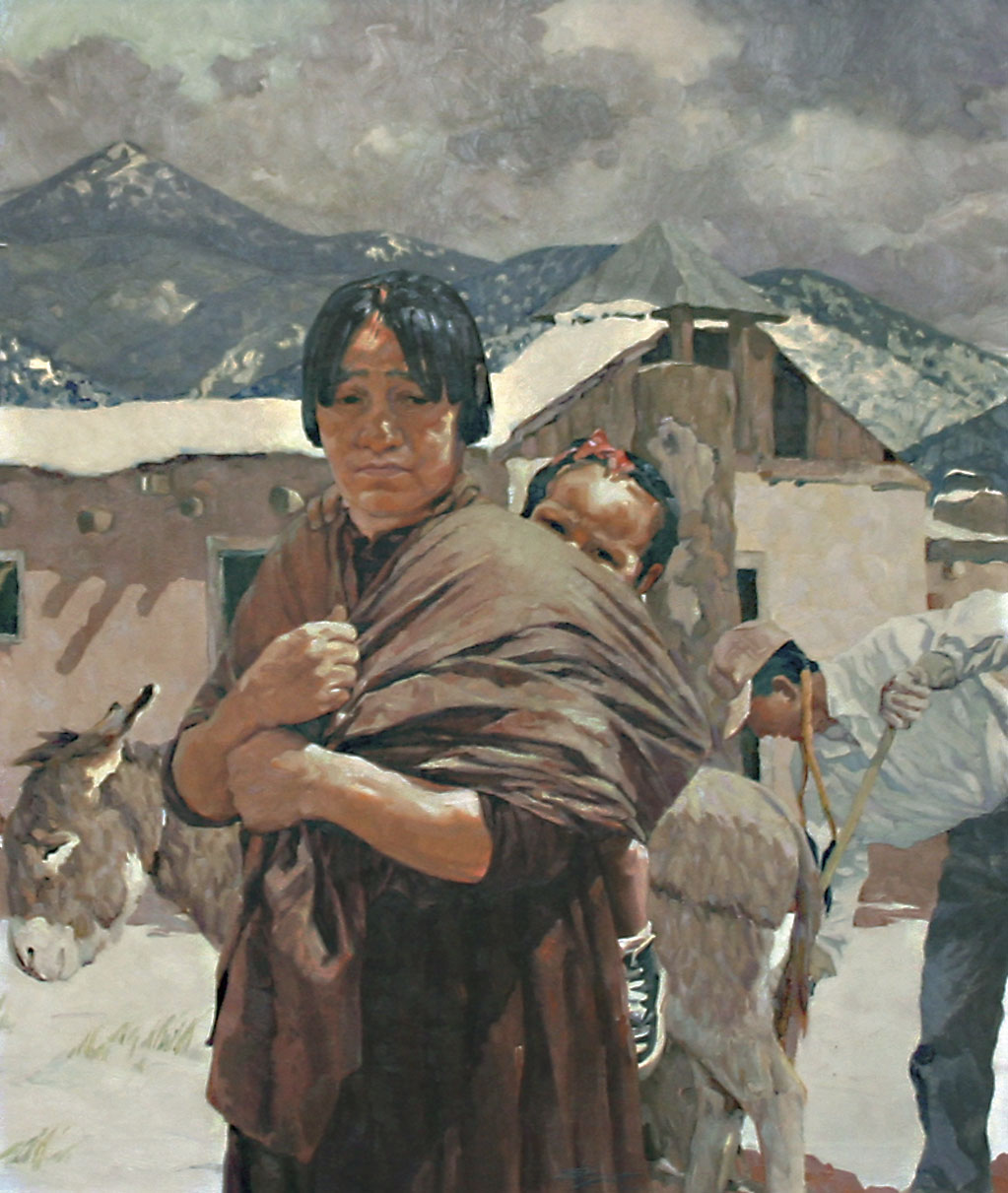

The wave of European Modernism that swept the country after the Armory Show in 1913 — a time when the aesthetics of formal art aspects resurfaced — is reflected in Sahula-Dycke’s earlier pieces, and it was a style he returned to again and again. In some of his more illustrative pieces, like Taos Madonna, this ability to capture the moment in such fine layers of veracity is a mark of his background as well as his talents.

Later on, during the tumultuous 1960s and 70s, he tilted his work to bring an emotional element to his palette. In Spring Rain, as well as Night of Three Moons, color-saturated landscapes attempt to link art and life, with an effort to convey the harmony in nature as well as the spiritual elements surrounding him.

“Like most European artists of the time, he had great training,” explains Michael R. Grauer, Curator of Art at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas. “And his work was skillfully executed.”

Grauer, who helped the museum acquire a 20-foot-wide Sahula-Dycke painting of Washburn, Texas, originally commissioned by a bank, continues: “He’s a heck of a good artist.” And despite the fact that he was very prolific, says Grauer, “You just never see his work on the market.”

It wasn’t until 1928 that Sahula-Dycke actually saw the country that had captivated him for so long. “Upon entering the Southwest, I felt at home for the first time in America. I felt the opportunity to become independent and cooperative at one and the same time,” he said in a 1953 article in The Cattleman. Years would pass, however, before the artist would move to the region.

Sahula-Dycke continued to work as a commercial artist and also began teaching at Chicago’s Academy of Fine Arts. All the while, he continued to study horses. “The anatomy of a horse is like a fine piece of literature. The bones are beautifully placed, like words in a sonnet. I never cease to marvel at the anatomy of a horse,” he told The Cattleman.

As the country headed into the Depression, the need to earn a better living led Sahula-Dycke to Detroit where he became an art director for Chrysler Motors. In 1937, he moved to Dallas to become art director at the prominent advertising firm Tracey Locke. He and his family lived there until 1945 when they moved to Dalhart, in the Texas Panhandle, so Sahula-Dycke could paint in a part of the country where life revolved around cowhands, horses, cattle, Indians and coyotes.

“We tend to cast aspersions onto commercial art, but in Europe that line is not as clear. Art is art,” explains Grauer, suggesting that Sahula-Dycke’s transition back and forth between commercial and fine art was one of economics, and was not something that troubled the artist. “He needed to make a living,” Grauer says plainly.

At one point, in late 1949 or early 1950, Sahula-Dycke decided his two sons, Ignatius and Peter, needed exposure to a wider world and moved his family to New York for a few years. He again worked as an art director and illustrated stories for Field and Stream, Harper’s Magazine, The Cattleman, Quarter Horse Journal and New Mexico Magazine, as well as illustrating several Hopalong Cassidy books.

Younger son, and celebrated photographer, Peter Sahula believes the move to New York was a sacrifice for his father. “He left after a couple of years, and my mother, brother and I remained while we were in school,” he says.

“Painting was his passion. There were years he didn’t give too much thought about earning a living. My mother worked at a local radio station. He would lock himself in his studio and only come out to eat. After he and my mother were divorced, he moved to Santa Fe where he had a studio on Canyon Road,” recalls Peter.

“He was well known when he lived in Santa Fe and was represented in the Jamison Gallery there. When the gallery closed, he was not represented anywhere else. It was after his death [in 1982] that our gallery began handling his paintings,” says Chavez.

Sahula-Dycke was a lifelong member of the Art Institute of Chicago; his work was exhibited there as well as the Scarab Club of Detroit, Art Directors Club of New York and the Museum of New Mexico. He painted murals in The Amarillo, the Herring Hotel, and Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch at Old Tascosa, Texas. Sahula-Dycke had solo shows in Houston, Dallas, Amarillo and Santa Fe.

Though Sahula-Dycke’s work is not widely available, there are pieces to be found and bargains to be had, says Grauer. “You can find them at yard sales and estate sales [around the Panhandle],” he says. His Springtime Reverie sold for $9,000 in 2000, and a Santa Fe watercolor was recently listed through secondary art brokerage house, Windsor Betts of Santa Fe, for $4,500. “The work is strong enough to support those kind of prices,” says Grauer. “But the market isn’t there…. He’s just not known.”

Ignatz Sahula-Dycke’s life and career twisted and turned from the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire through major centers of American commerce to the plains of Texas and the mountains of New Mexico. The heritage of the West and Southwest is richer for his love of the beautiful land and its people.

“I think Sahula-Dycke’s work is an accurate representation of life in Texas, New Mexico, Colorado and Arizona during the years he painted,” says Chavez. “He made an important contribution to the region, and more people should be aware of and enjoy his paintings.”

Editor’s Note: Sahula-Dycke’s paintings can be seen at Tito’s Gallery on Bridge Street in Las Vegas, New Mexico, and at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas. David Dike Fine Art in Dallas occasionally handles his paintings. His work is also on exhibit at Toklat Gallery in Basalt, Colorado.

Paulette Dininny is an Easterner captivated by the West and Southwest. Her interest in the region probably grew out of playing rodeo and cowgirl as a child. The former reporter, who writes for national magazines and newspapers, loves to find good stories to share with readers.

- “Springtime Reverie” Oil | 24 x 30 Inches | circa 1950

- “Protecting Her Own” Oil on Canvas | 20.5 x 30.5 Inches | circa 1968

- “Spring Rain” Oil/Varnish | 20 x 24 Inches | circa 1980

- “Taos Madonna” Oil on Canvas | 35 x 42 Inches | circa 1965

- “Night of Three Moons” Acrylic | 20 x 24 Inches | circa 1978

No Comments