01 Feb Influence of the West

WHAT MAKES A JOHN FINCHER A WESTERN ARTIST, at first glance, simple geography. Born in Hamilton, Texas, schooled at the University of Oklahoma and working for the past 30 years from a studio in Santa Fe, his experience with the landscape west of the Mississippi informs his work in any number of ways.

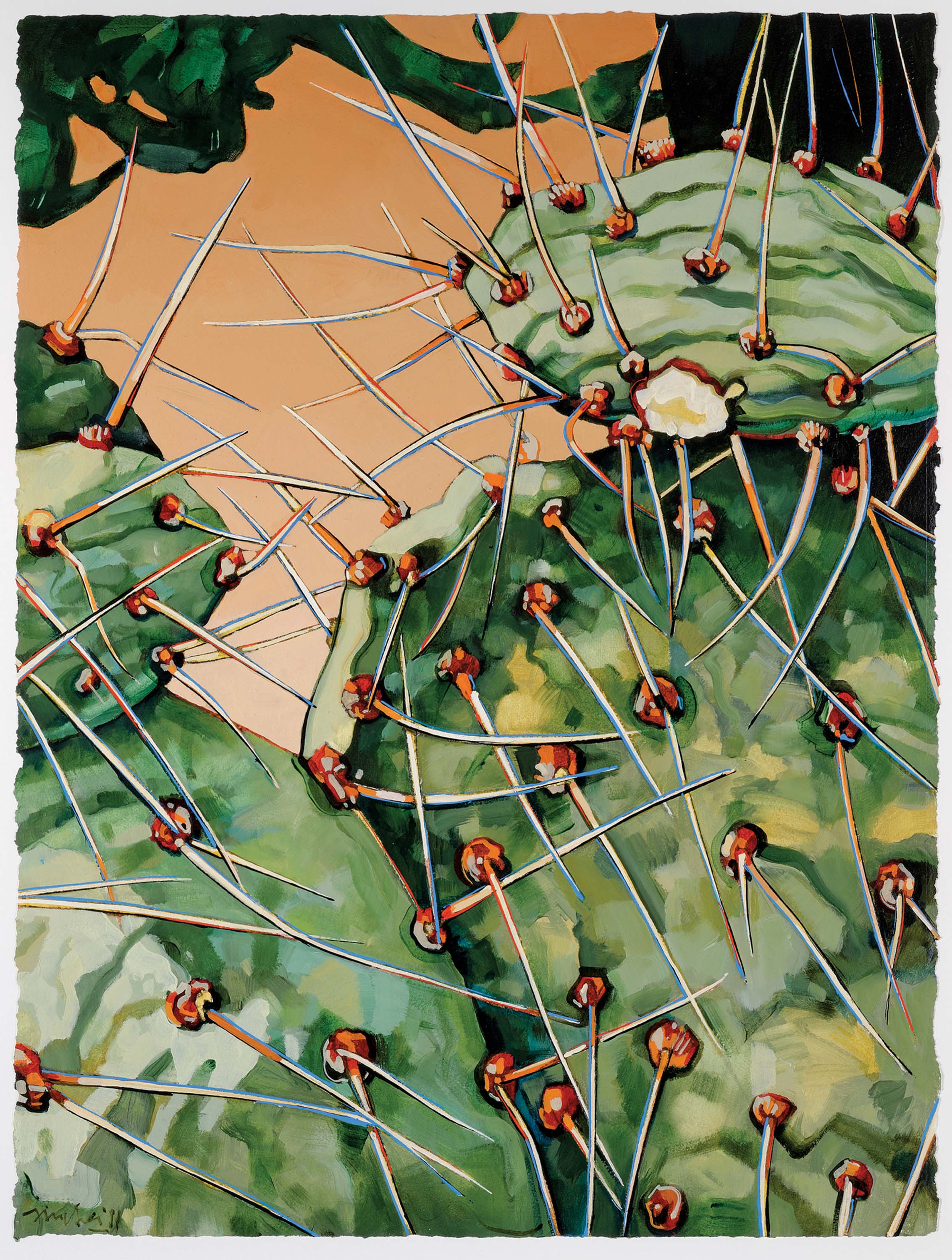

“Fincher has the eye of a sage, seeing in small details of Western landscape, as unassuming as cactus spines and poplar trees, the timeless and enduring strength, integrity and rustic beauty that have come to signify a powerful aspect of the American character,” says Kenneth R. Marvel, co-owner and CEO of LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe, where Fincher shows his work.

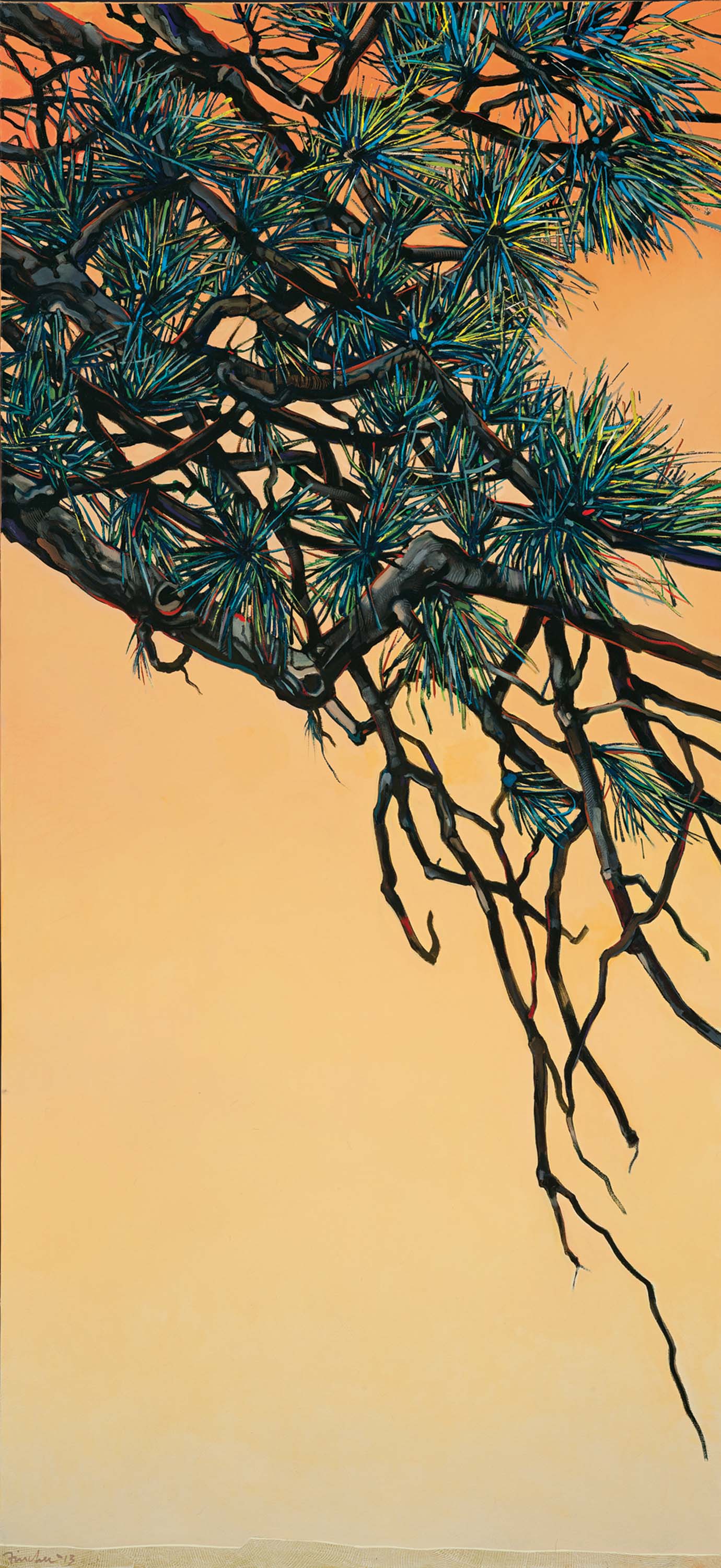

A colorist extraordinaire whose canvases undulate with an otherworldly luminosity, Fincher has offered up revolutionary interpretations of landscape paintings, turning the picture plane on its side to contain vertical images of singular forms that represent a seemingly endless panorama.

“I am a true romantic painter,” Fincher says. “Painters who I have admired from the past — Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, John Singer Sargent — employ a certain theatrical emphasis that takes you out of your world and projects you into something more beautiful and more heaven bound.”

In Fincher’s representations of the ubiquitous poplar tree, sinewy trunks soar beyond the confines of the canvas, giving way to clumps of vivid colors layered in thick brushstrokes that represent clusters of impossibly hued leaves. The strong sense of movement upwards accents the spiritual essence of the tree.

“It lifts you out of your everyday world into a more beautiful dimension,” Fincher says of the apostolic forms. “It’s a piece of magic.”

Fincher has a history of working with totemic forms. Starting in the 1970s, he began rendering vertical objects isolated in empty fields with a single shadow.

“There is an existential element to them,” he explains. “Vertically reaching upward has become a signature of mine.”

Adding to the spiritual tonality of the work is Fincher’s own use of light and the manifestation of luminosity.

“There are several paintings under almost every one of my paintings,” Fincher says. “Having light radiating from behind the image is an old technique that goes back to Georges de La Tour and his use of candles. I have always found it intriguing and a way to add a spiritual aura.”

Fincher’s use of color is sophisticated, bold and subtle, all at the same time. There are rich, textural strokes of alizarin crimson overlaying burnt umber or cadmium light, but his complex process imbues so much more into each work.

“Fincher’s nuanced sense for contrasting color and interplay between small and large, mediums and mythic meanings imbues his canvas with a sense of delight and reverence,” says Marvel. “There is a direct honesty, both in his paring down of a majestic landscape to common details and in his audacious use of electric color and vivid shadowing that imparts a sense of the energy and optimism associated with the land he paints.”

Gnarled yet sturdy pine limbs, sparsely clad in tufts of conifer needles and outlined against benign blue skies or golden waves of hillsides, add a mythic and decidedly Western narrative to the work.

“The way the West has influenced my recent work over the last 15 years is mysterious,” Fincher says. “I am 6 feet tall and I can back away from a canvas and then move into it with my whole body. I use a big brush and work large.”

Fincher was born in 1941. His father, although not a serviceman, drove a cattle truck from Central Texas to Fort Worth to help feed the troops. An only child, Fincher was often on his own. He began to draw, and when his parents recognized natural aptitude, they hired a local painter to teach their son technique. Years later, Fincher entered Texas Tech and majored in advertising art and design.

“When I got my hands on paint, I knew I had found what I wanted to do,” he says.

Fincher won a fellowship to the University of Oklahoma where he earned his master of fine arts degree under John O’Neil, who would later establish the visual arts program at Rice University.

“I came to Santa Fe at a time when young artists were portraying Western iconography and landscape in a contemporary fashion that was essentially a form of illustration,” Fincher explains. “We were labeled the new Pop artists of the new American West.”

Fincher found fame going with the art world flow, however by the mid-1980s he was ready to move on to more diversified subject matter. And, although his work would continue to reference a butte or the silhouette of a mesa, it took on a universality that went beyond his immediate environment.

“It became another way I could define myself,” he says. “We are all subjects of our environment. When I go out my back door, I still see mountains and there is a beautiful cactus growing on the south side of my studio. It all influences me on a subliminal level.”

When Fincher begins to paint, the close-up composition of the beautiful cactus may become a threatening horror-show perspective of deadly needles pointed directly at the viewer. Or a series of fence posts arranged in a seemingly random pattern across a canvas become symbols of the settling of the Wild West.

“The most attractive works of Contemporary Realist painting, such as those of John Fincher, are those that vividly reveal that the artist’s intent is not to ‘represent,’ but to share his sensations vis-à-vis the subject matter,” says Jan Adlmann, former assistant director for external affairs at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. “As someone famously put it: ‘A poem must not mean, but be.’”

- “Cascading Pines” | Oil on Linen | 70 x 32 inches | 2013

- “Fence Break” | Oil on Linen | 25 x 30 inches | 2005

- “Around Placitas” | Oil on Linen | 72 x 48 inches | 2012

- “Night Garden” | Oil on Linen | 24 x 36 | 2014

- “Fence Break” | Oil on Linen | 25 x 30 inches | 2005

- “Summer Cactus” | Oil on Paper | 30 x 22 inches | 2011

- John Fincher

No Comments