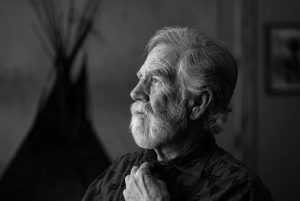

06 Sep Inner Light

At first glance, Fort Mountain, a recent large-scale landscape by R. Tom Gilleon, impresses with its breathtaking majesty and deft virtuosity alone, presenting a mid-range view of the title subject surmounted by a vast, cumulus-filled Montana sky. Then, like a hallucination, the scene somehow transforms. To a stirring soundtrack, a buffalo materializes and then vanishes while its herd enters, kicking up dust. As the sun sets, Native Americans on horseback appear in the distance, raise tipis, and light fires.

Fort Mountain | Oil on Canvas | 40 x 60 inches | 2020

Though Gilleon’s gracefully bravura style, which he modestly describes as “loosely realistic,” is unmistakable, this is definitely not one of the oil-on-canvas works that have secured his stellar reputation in the fine art world during the three decades since he moved on from Walt Disney Imagineering, where he served as a leading concept illustrator. And yes, he has also painted oil-on-canvas versions of Fort Mountain. This piece, however, done in collaboration with fellow artist, tech innovator, and former Disney colleague Marshall Monroe, marks a bold new venture: a high-definition “digital painting.”

Using a program that enables him to replicate traditional effects so closely “that you can put big, blobby oil brushstrokes onto your digital canvas,” Gilleon produced 32 individual paintings of Fort Mountain in his computer, while Monroe created such digital animation effects as the dust cloud, smoke from a tipi, a lightning storm, or falling snow. “The transition is subtle,” Gilleon says, “as one painting fades out and the next one fades in, while the mountain’s silhouette never changes during the 19-minute loop.” (To view an excerpt, visit westernartandarchitecture.com.)

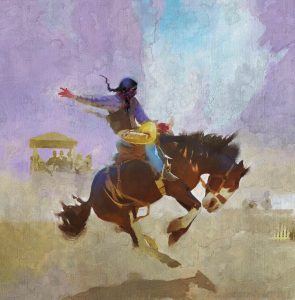

No flat-screen display is necessary, however, for art lovers to experience most of Gilleon’s in-demand paintings, which — though made with real oils on canvas — emanate their own vibrant energy. “Light seems to come from within them and just grab your soul,” says Maria Abad, director of Montana Trails Gallery in Bozeman, Montana, which will show his latest works from November 18 through December 31. “Even the best photos give you no clue of how phenomenal they are when seen face-to-face.” Not surprisingly, they can command six figures, with his recent Dirge with Black Feet fetching the top price of $375,000 last winter in Los Angeles at the Autry Museum’s Masters of the American West show.

Another Bucker | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 60 inches | 2022

Ralph Thomas Gilleon grew up making art on an epic scale. Born in Gainesville, Florida, in 1942, he was raised by his grandparents, whose white-sand yard became the boy’s canvas for stick drawings. He also learned vital lessons from his grandmother Ruby Nettles, “a wonderful person,” an artist herself, and a full-blooded Cherokee. “‘You have to learn not to depend on anyone, especially me,’” Gilleon recalls her telling him with tender sternness. “And she would teach me little survival skills, saying, ‘You learn to do this and you’ll never have to take their government cheese.’”

Beaver Creek | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 30 inches | 2001

His independent streak thus lovingly nurtured, Gilleon won a baseball scholarship to study architecture at the University of Florida; but sensing his future lay elsewhere after his freshman year, he joined the Navy. After leaving the service, Gilleon studied at the Art Students League of Brevard, Floria, and began illustrating professionally. By the mid-1970s, while thriving as a freelancer, he caught the attention of the creative team at nearby Walt Disney World, which hired him to execute concept designs for EPCOT, the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. During two decades with Walt Disney Imagineering, Gilleon captured visions for theme parks, attractions, and shows around the globe.

Red Bush | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 36 inches | 2019

“Tom was not only the finest person with whom you could have a collaborative conversation, but he also had the ability to create this moment of illuminant tension that made our concepts come off the page with emotion and spiritual energy,” says Bob Weis, former President of Walt Disney Imagineering, now its Global Ambassador, and a close collaborator with Gilleon for more than two decades. “He had the genius to encapsulate in one image everything we’d been talking about over a two- or three-year period, to capture everyone’s imagination and — humbly, quietly, collaboratively, and without ego — make the difference between whether or not a project would happen.”

The Mission | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 60 inches | 2022

Back in January 1982, during an Imagineering art retreat at a dude ranch in Augusta, Gilleon got his first taste of Montana. He fell in love with the setting and managed to continue his exclusive affiliation with the company from the home he and his then-wife built over 10 years along the Dearborn River, and then on a 2,000-acre ranch where he now lives about 25 miles south of Great Falls. Legendary Western artist Charlie Russell had cowboyed, painted, and sculpted on that same land a century before. “I very much identified with Russell, who had a do-it-yourself attitude like my grandmother always encouraged in me,” Gilleon says.

Pair and a Spare | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 48 inches | 1994

Inspired by the region’s grandeur, Gilleon ventured into fine art. “That’s an extremely hard transition for many artists,” he says, explaining that his change was eased by a Disney retainer that came “whether they needed me or not.”

One day, with a large, square, blank canvas sitting in his studio, he stared out the window and decided to paint a tipi he’d erected outside. “I still remember thinking that this might be a waste of canvas and paint,” he says. His gallery instantly sold it to a lodge in Big Sky. “And suddenly, there was a demand for my tipi paintings.” Two decades later, he reckons he’s sold hundreds — a recognition of the icon’s power, its mutability, and Gilleon’s talent. “Every tipi you see in real life is decorated differently,” he says. “It’s a sort of canvas for the art of the people who live in it.” Says Gilleon’s friend Dugan Coburn, a Blackfeet knowledge keeper and the Director of Indigenous Education for Great Falls Public Schools, “Tom is always inquisitive, wants to know the Blackfeet stories, and then comes up with his own authentic images to tell them.”

Pemmican | Oil on Canvas | 50 x 50 inches | 2021

Not that he paints tipis alone. His range embraces Native faces and figures, landscapes, grain elevators, and other iconic Western images. Whatever the work, Gilleon now does all his preliminary studies on the computer, up to actually completing a work digitally. Only then does he move to his easel, painting the final work in oil on canvas while referring to the digital image on a nearby monitor. “It’s a totally different mode than the old way,” he says.

Evolving Evolution | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 120 inches | 2021

Considering how his approach has evolved with the passing of time prompted him to muse on his legacy during an airplane flight two decades ago. “What if an artist knew that his next painting was to be his last?” he wrote on a notepad. “What would he choose to paint? How careful would he be to make this one the best he has ever done… make every brushstroke be purposeful, effective, and masterful?” Such questions led Gilleon to begin a new chapter in his creative life, now designated as his “MMXX Vision.” Each designated “masterwork” is produced with a profound awareness of life’s finite quality and of the rich artistic legacy he will someday leave.

Tom Gilleon paints at his ranch in a spacious studio filled with true north light.

No Comments