04 Aug Inside Indian Market

EVERY YEAR AT THE END OF AUGUST when the sun is warm and the light is golden, Santa Fe, New Mexico, hosts the largest juried Indian Market in the world. Thoroughfares lead like spokes of a wagon wheel to the central square where performances of traditional music and dance provide an authentic background to the comings and goings of turquoise-clad visitors.

When artists set up booths as early as 4:30 a.m., the air holds just a hint of the fall weather ahead. Fires are stoked — albeit from commercial stoves — and the aroma of roasting corn, green chiles and Navajo fry bread drifts over the ever-building crowd. Crates are cracked open amid circles of family vendors often in Native dress. And the murmur of Native tongues rises and falls in discussion, perhaps about sales to be won that day.

For nearly a century, Native American artisans have gathered in the streets to present authentic craftsmanship to a global audience that has grown to 120,000 souls. This year, more than 1,000 Native American artists will vie for more than $100,000 in prizes and, of course, sales.

What began as an indigenous art fair has morphed into a festival of multiple art forms and events. Starting a full week before booths are erected down the center median of narrow Santa Fe streets, offerings in film, fashion, books, music, dance and a signature gala with silent auction are on tap.

Numerous art forms are on display: jewelry, pottery, sculpture, textiles, paintings, wood carvings, beadwork, baskets and a catch-all category called “diverse arts” that includes drums, bows and arrows, and cradle boards.

I have been going to Indian Market for a number of years and have watched it grow and expand. It is a democratic cultural experience, with the serious collector and the simply curious coming together for an enriching encounter with Southwestern tradition and contemporary art.

My family moved from the Midwest to New Mexico in 1970 and none of us were ever the same. For us, the new landscape, the new cultures, the new horizons melded together in the traditional arts of the indigenous peoples. The black pottery from the Santa Clara pueblo spoke to the obsidian depths of a pantheistic spirituality as did Zuni animal fetishes carved from serpentine, turquoise and antler.

Weavings that told the ancient stories — of the three sisters or the four directions or the trickster coyote — were found in rugs and blankets, wall-hangings and clothing. Pawn shop turquoise, silver concha belts and necklaces created from impossibly large silver squash blossoms came out at night with our new friends and neighbors. We learned quickly how to spot the real thing and watched in dismay as the trickster coyote became a baying image on anything that might be sold to tourists.

My mother was inspired to pursue her love of archeology, and worked to preserve Navajo burial grounds in northern New Mexico. She collected historic pottery and silver, but also stories passed down for generations by those she met while she walked her path.

Indian Market was much smaller when I started attending in the 1970s but just as diverse and dignified as the event today. Enthusiastic visitors from neighboring states came then, as now, with eagerness expressed through endless ropes of turquoise and silver and bolo ties with big rocks as fasteners.

I try to never miss a market. I look for the new by contemporary artists, but also the traditional crafts carried on by mothers and daughters, by fathers and sons, and by techniques learned from ancient, wrinkled grandparents.

I go early and leave early, gorge on breakfast burritos and green chile stew. I do my homework so I can be ready when the dealers I most admire are ready to open shop and spend the days feeling grateful for my small history here.

At Indian Market, plotting in advance will get you far

Ask Della C. Warrior, the director of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, how to best “do” Indian Market and she will tell you preplanning is key.

“A lot of the work in our collection includes work that is featured in Indian Market,” she says. “I suggest buyers come up here to the museum to become familiar with the historical artifacts, traditional works and contemporary pieces, as well as the work of the various tribes.”

More than 200 tribes recognized in the United States as well as First Nations Tribes from Canada are represented at the market. To help navigate the events and the maze of booths, the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA) puts out The Official Indian Market Magazine, filled with a calendar and useful information, plus profiles of featured artists. The Santa Fe New Mexican also has a special Indian Market guide with 167 pages of photos, stories and a booth locator map. Both are available at the Santa Fe Convention Center.

I like to stop in at the Santa Fe tourism office located at the convention center. The women working the front desk are welcoming, knowledgeable and will provide you with recommendations for everything from food booths to special events.

“I go through the list of participating artists and familiarize myself with them,” says Douglas Sill, a dealer from Minnetonka, Minnesota, who also acts as a judge for the Best of Show competition. “The week leading up to market, I go to as many events as I can from gallery openings to museum exhibitions and, of course, to the preview on Friday night. If you don’t do your homework, it can be overwhelming.”

Kick off the weekend on Friday, August 21, with the Sneak Peek

Dallin Maybee, interim chief operating officer for SWAIA, never misses this event.“The artists who enter the competition for Best of Show and who have been selected from hundreds of submissions clearly have the best pieces,” he says.

The Friday evening preview of the show’s prize winners, displayed in the center of a convention center room on an elevated platform, allows for up-close-and-personal viewing. The Best of Show Award — selected by a knowledgeable jury that includes gallerists, curators and artists — is considered the most prestigious in Native American art. The preview, an essential part of preshow homework, provides context and a chance to compare and contrast work you will see in the general show.

On Saturday morning, August 22, the early bird gets the worm

Go early. The artists begin setting up the night before market, so beat the crowds by taking your coffee on the run. I usually mosey over around 7 a.m. This gives me the chance to speak with the artists and take in as much as possible before buyers are three deep at every booth. You will have the run of the market until around 10:30 a.m., when numbers begin to skyrocket.

Go ahead and feed your soul with art … but don’t forget your belly

I find it is always good to break for lunch. Not only can you get off your feet for an hour or so, but you can also regroup and outline the afternoon plan of attack. There are food vendors with booths right in the thick of Indian Market offering Navajo tacos, Indian fry bread and other northern New Mexico delicacies.

But I almost always opt for the La Fiesta Lounge at La Fonda. The oldest hotel in the oldest capital city in the United States is located just off the plaza on East San Francisco Street. The historic property is filled with an impressive collection of regional art and offers a Northern New Mexican buffet — all you can eat — for $13.95. Chef Lane Warner, a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York, locally sources organic meats and produce and has become famous for his chile rellenos.

Sunday, August 23, is the day to close the deal

Sunday is bargain day — at least at some of the booths.“On Saturday I like to go shopping and see as much as I can,” says Della Warrior. “Then I go back on Sunday to buy. I like to see if the prices have gone down.”

Bargaining at most booths is encouraged, although I am not convinced there are any real deals until late Sunday. When you bargain, come up with a price with which you feel comfortable, and be willing to walk away.

The Indigenous Fine Art Market adds to the celebration

Last year marked the successful launch of an avant-garde splinter group selling down at the Santa Fe Railyard Arts District. The Indigenous Fine Art Market (IFAM) offers another opportunity to meet and see the work of emerging artists in a wider variety of media including printmaking, anime and graffiti art. The group was formed after a controversial split with SWAIA when about three dozen artists expressed their desire to create a market that represents Native culture as it exists today.

Artist and poet Bunky Echo-Hawk, who is also a designer for Nike’s indigenous art-inspired line, N-7, puts it this way: “I like to call it ‘Neo-Native.’ It’s a contemporary platform that allows us to reclaim our visual identity,” he says.

The juried show will be back in 2015 with 250 booths and about 300 artists. IFAM differs from Indian Market in that artists don’t register by art form, so in any booth you may find one artist showing paintings, pottery and beadwork.

I will be back at the market this year, and I will see old friends and make new contacts. I always marvel at the amount of joy that spills out over the square — expressed by children dancing with abandon, the proud smiles of merchants selling their wares, in the eyes of visitors who have just discovered new artists or art forms created by the amalgamation of new and old. For me it is so much more than coming home.

- More than 1,000 Native American artists set up in the streets surrounding the square with works ranging from traditional tribal arts to Neo-Native offerings. Performances of traditional music and dance are scheduled throughout Saturday and Sunday, and there is plenty of opportunity to visit with the artists themselves. Photo: Robert Mesa

- More than 200 tribes recognized in the United States as well as First Nations Tribes from Canada are represented at the market.

- Sometime referred to as the “other” market, Indigenous Fine Art Market (IFAM) was started in 2014 as a celebration of indigenous art and the cultures that inspire it. In addition to juried art, IFAM includes youth, music and literary programs and exhibitions to create a greater understanding of the diversity of Native American culture and people. This year’s IFAM events take place at the Santa Fe Railyard from August 20 to 22. Photos: Gabriella Marks

- Performances of traditional music and dance are scheduled throughout Saturday and Sunday, and there is plenty of opportunity to visit with the artists themselves.

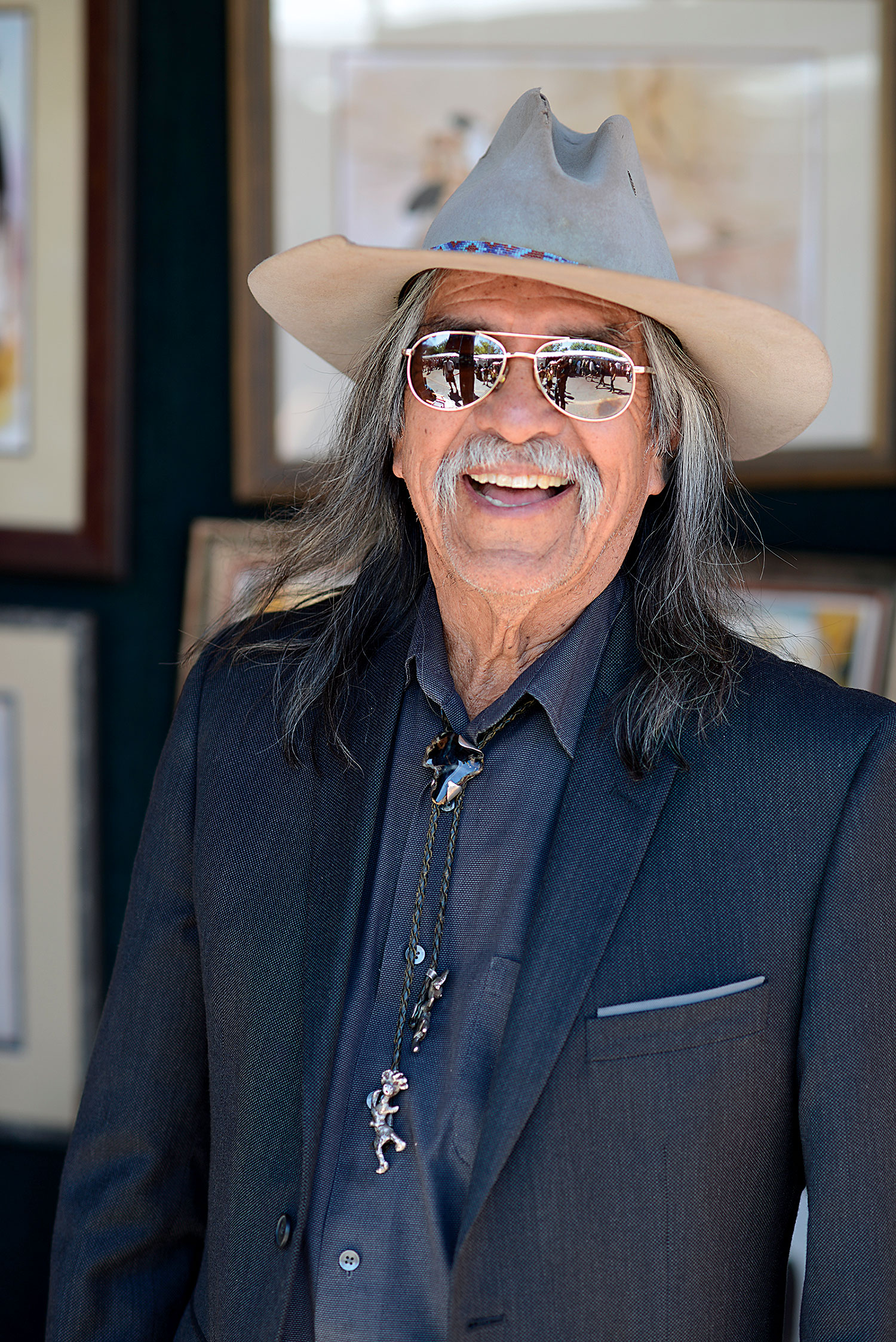

- Indian Market is a family affair and a tradition passed down through generations. Photos: Daniel Nadelbach

- Sometime referred to as the “other” market, Indigenous Fine Art Market (IFAM) was started in 2014 as a celebration of indigenous art and the cultures that inspire it. In addition to juried art, IFAM includes youth, music and literary programs and exhibitions to create a greater understanding of the diversity of Native American culture and people. This year’s IFAM events take place at the Santa Fe Railyard from August 20 to 22. Photos: Gabriella Marks

- More than 1,000 Native American artists set up in the streets surrounding the square with works ranging from traditional tribal arts to Neo-Native offerings.

- Award-winning jewelry and textiles are two of the most popular items on sale. Photo: Daniel Nadelbach

No Comments