18 Dec INTO THE FIELD

WHEN WE THINK OF AN ARTIST’S STUDIO, we imagine a well-used space, often with good northern light and room for canvas, paint, clay, brushes and whatever other equipment might be needed for the act of artistry. We probably don’t imagine it being on wheels. But for some artists, traveling to their chosen subject with more than a camera or sketch pad — taking along the whole studio or darkroom, in fact — is the only way to do what they love.

Here’s a look at two painters and a wet-plate photographer and how art on the open road impacts their practice and enhances their life.

Walt Gonske

There have been plenty of occasions when painter Walt Gonske, from Taos, New Mexico, has parked at a gorgeous vista overlooking the Pacific Ocean, ready to set up his easel and work, when not 10 minutes later a car or bus pulls up and a load of people spills out. And every few minutes, more tourists wander by.

“If not for the paintmobile, half of them would want to come talk,” Gonske says. “They think if I’m out there painting I must be an extrovert, and they assume I want to talk.” But he doesn’t; he wants to paint. And thanks to his beloved “paintmobile,” no one even knows he’s inside, easel set up near an open window, painting away.

Gonske’s mobile studio is a tall, sturdy, custom-built, 7-by-15-foot aluminum box on a heavy-duty Ford chassis with dual back wheels. It’s his fourth paintmobile so far, and in his view, the best. For the first 13 years of his career, Gonske painted outdoors, enduring whatever came along. Then in 1985, he bought a van and had it modified with custom-cut windows and an extended fiberglass roof, so the 6-foot-3 landscape artist could stand inside by any of several windows at just the right height. Since then, he’s designed increasingly improved versions and happily avoided chatty people, rain, cold, bugs, snow, sun and wind. Without his paintmobile, he says, many a landscape-hunting foray far from home would have found him “killing the day in a coffee shop, reading a novel.”

These days, Gonske often spends as much as three months a year in the paintmobile, including day trips. He has taken it to California and the East Coast, although his favorite territory is Northern New Mexico and Western Colorado. “I just keep finding things to paint right here,” he says. Late spring is for Colorado, when snow remains in the mountains but the roads are clear. Then it’s apple blossom season along New Mexico’s Rio Grande. In summer, he works in his home studio — the paintmobile can get hot — and in fall he’s on the road again.

Gonske keeps his rig stocked with painting supplies stowed in specially designed cabinets. A heavy worktable on wheels, with an attached easel and palette, is secured to the wall for traveling. There’s a bunk for occasional naps and a cooler for snacks, but generally the 75-year-old artist spends nights in motels. He also carries along a French easel, just in case the best composition requires leaving the paintmobile.

“But I have to admit,” he says, “I’m so spoiled by that thing, I hate to get out of it.”

Eric Overton

Eric Overton uses more or less the same photographic equipment and techniques as mid-19th-century photographers who captured images of wild, remote regions of the West. The wet-plate process involves an enormous field camera on a tripod, chemicals and large plates of glass. The main difference: Early photographers hauled their heavy camera and developing equipment, along with food, clothing, gallons of water and canvas tents that served as portable darkrooms, on the backs of mules. Overton carries his in a Toyota pickup truck with a camper shell. Plus, unlike back then, he has excellent maps.

Yet, despite the relative speed and ease with which he reaches such places as Yellowstone or Joshua Tree, it’s actually the slow, tedious nature of the ambrotype process that attracts Overton to this anachronistic method of making art. The 37-year-old photographer, who’s based in Salt Lake City, Utah, and is also a sculptor, filmmaker and doctor, began using wet-plate photography as a way to slow down and physically connect with photography and the landscape. (The same desire for a more human pace inspired him to open an integrative concierge medical practice, offering a combination of conventional techniques, acupuncture and herbal approaches to a relatively small patient base.)

Before each photographic excursion, Overton consults a 30-plus-item checklist — including various chemicals, camera parts, tripods, dark cloth and boxes to hold the glass plates — so he won’t forget anything. Once out on the land, he creates a mobile darkroom by enshrouding the truck’s camper shell with a heavy cloth. He sits inside and works by the red light of his headlamp to prepare the glass plate before inserting it into the camera and bathing it in chemicals after taking a shot. He sleeps on top of the truck on a sturdy roof rack and eats very little while out in the field. “I’m obsessed when I’m in work mode, and I don’t feel hunger,” he says.

At some point, Overton envisions creating ambrotype portraitures — early in his career he shot portraits with regular film for such magazines as Rolling Stone. For now, it’s the majestic landscape of the American West that continues to call and which reminds him of why he’s out there in the first place.

A few years ago at Bryce Canyon, torrential rains kept Overton in his truck cab for hours, and when the rain stopped, clouds obscured all views. After allowing his initial frustration to pass, he found himself sitting on the canyon rim, soaking up the sounds, smells and feelings that only such a place can offer.

“The whole point of this project,” he says, “is to experience something real and natural and to find solace, comfort and beauty in the landscape just by being there.”

Jerry Ricketson

Painter Jerry Ricketson woke up one morning, rolled over and looked out the window. All he could see were trees. He had no idea where he was. He racked his brain but could not even guess what state he was in. As he lay there, he gradually remembered: The previous day’s drive had brought him to a campground near Glacier National Park, where he’d pulled in late.

Such moments can happen when you’ve spent five years on the road full time in an RV-turned-art-studio. But for Ricketson, the bigger challenge is finding room for everything he needs to live and work in a 300-square-foot space.

Ricketson dreamed for many years of traveling the country to paint. “When I turned 55, I thought, ‘If I don’t do this now, when will I?’” he says. In late 2012, he sold his house in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and almost everything in it. He bought a 32-foot fifth wheel and a one-ton dually pickup truck to pull it.

Sitting outside his rig at a leafy North Carolina campground, he talks of the road. In a few days, he’d be heading to New England for fall colors, then south again for warmth, then west to spend the winter in Texas, New Mexico or Arizona. He explores each place, gathering photos and sketches for painting back in his rig.

Before becoming mobile, the studio filled the entire second floor of Ricketson’s Tulsa home. Adapting to a fraction of that space took some ingenuity and time. At first, he tried keeping the RV’s interior as it was, setting up only the essentials to paint. But that wasn’t working, so he removed the sofa, dining furniture and two plush rockers. A large cooler topped with a board serves as his worktable, with painting supplies stowed inside while traveling. He uses a tall custom-built table for stretching canvases and framing, and stores finished, dry paintings in narrow boxes underneath. When it’s time to move, he takes down his special lighting, packs away his paraphernalia and prepares the rig itself, all of which takes a full day.

Ricketson spends at least a month in each place, experiencing his chosen subjects in all kinds of weather and light. “It allows me to slow down, take my time, and be more selective about what I paint,” he says. A typical year sees him meandering through the South, Southwest and Montana, with the West Coast, Wyoming and Utah on his “before-long” list. And he has no intention of settling down.

“When I sold my house and started this, some of my friends felt sorry for me for not having a home,” he says. “Now, they’re a little envious.”

Catch these artists-on-the-move during their upcoming exhibitions

A 45-year retrospective of paintings by Walt Gonske runs through January 6 at the Taos Art Museum in New Mexico. Taken from the artist’s private collection, the show moves to Nedra Matteucci Galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico, from June 24 through July 21, 2018.

Jerry Ricketson is part of NatureWorks Show and Sale in Tulsa, Oklahoma, from February 22 through 25, an annual exhibition to benefit Oklahoma’s wildlife conservation.

Eric Overton’s ambrotype photographs are featured in a solo exhibition, Monument, from January 19 through March 17, at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Walt Gonske, “From the Valdez Rim – First Snow” | Oil on Panel | 18 x 24 inches

- “Yosemite #1” (detail) | Pigment Print Ambrotypes | 10 x 8 inches | 2016

- “On the Edge of Taos” (detail) | Oil | 24 x 28 inches | 2017

- Walt Gonske peeks out from his paintmobile.

- An important component to Eric Overton’s work is having his son involved in the process.

- Jerry Ricketson at work in the field.

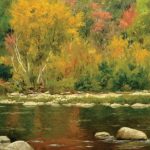

- Jerry Ricketson, “Fall on the Deerfield River” | Oil | 24 x 28 inches | 2017

- “Park Cottonwoods” | Oil on Linen | 26 x 32 inches

- “Campo Santo de Chamita” | Oil on Linen | 22 x 30 inches

- “El Prado Chamisa” | Oil on Linen | 24 x 26 inches

- “Indian Creek #2” (Bears Ears) | Pigment Print Ambrotypes | 10 x 8 inches | 2017

- “Evening Service” | Oil |16 x 20 inches | 2017

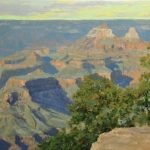

- “Canyon Shadows” | Oil |16 x 20 inches | 2017

No Comments