12 Sep Kyle Polzin

THE TERM “AMERICANA” IS OFTEN ASSOCIATED WITH MUSIC, but when artist Kyle Polzin uses the word to describe his work, it harks back to the original meaning, which, according to Webster’s Dictionary, has referred since 1841 to “materials concerning or characteristic of America, its civilization, or its culture.” It’s the perfect word to describe the essence of Polzin’s style and subject matter.

Tuesday Delivery | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 40 inches

“I prefer the term ‘Americana painting,’ rather than ‘Realism,’” Polzin says. “My work is all pre-plastic: it’s leather, wood, patina on brass — stuff that carries the marks of age, because I want each of my paintings to be an encapsulated little world, a showcase of objects from another time period.” This often involves objects made by hand: saddles, boots, powder horns, and headdresses. “I’m drawn to the grittiness of the old Western stuff,” Polzin explains. “It’s been worn, and used, and it tells a story by itself.”

It’s easy to look at one of Polzin’s paintings from a distance and make the mistake of thinking it’s a photograph. “I’m not going for photorealism,” Polzin clarifies. “But I do want the painting to look real.”

There’s no question that his work is infused with that reality; Polzin has a talent for painting ordinary and aged remnants of the American past in a way that celebrates the grittiness of history and its artifacts. That gritty impression appeals to all of the senses. In Boots, for example, one can practically smell the well-worn leather, the faint tang of manure clinging to those bulldog heels, and even the dust on the wood floor.

Pap’s Stash | Oil on Canvas | 13 x 18 inches

That sensory experience is something that distinguishes Polzin’s work from the school of hyper-realism. Through the judicious application of glaze and the manipulation of the paint’s texture, Polzin ensures there’s what he calls a slight “fuzziness” to the finished product. “For certain patches of leather or wood in the painting, I add scratches to the surface of the paint, and then I might add some glaze, which, when the light hits it, produces a depth, a kind of radiant glow,” he says.

This process enhances the trompe l’oeil effect, as if the viewer is looking at the objects through a window into the past. It’s an uncanny effect, one that compels the viewer to see a story behind the work. And for Polzin, it’s all about this narrative: “I want the painting to evoke a story in the viewer’s mind, some memory of the past. That’s kind of the power of these old artifacts and objects.”

Powder and Perseverance | Oil on Canvas | 15 x 47 inches

At times, Polzin goes to great lengths to procure the objects he intends to paint. Once, he drove from Texas to Nebraska to find a vintage, authentic canvas-covered canoe to put into a composition. For Into New Territory, he went a step further. Unable to find an authentic scrimshaw powder horn, he sat down and carved his own; then, he painted it into the composition.

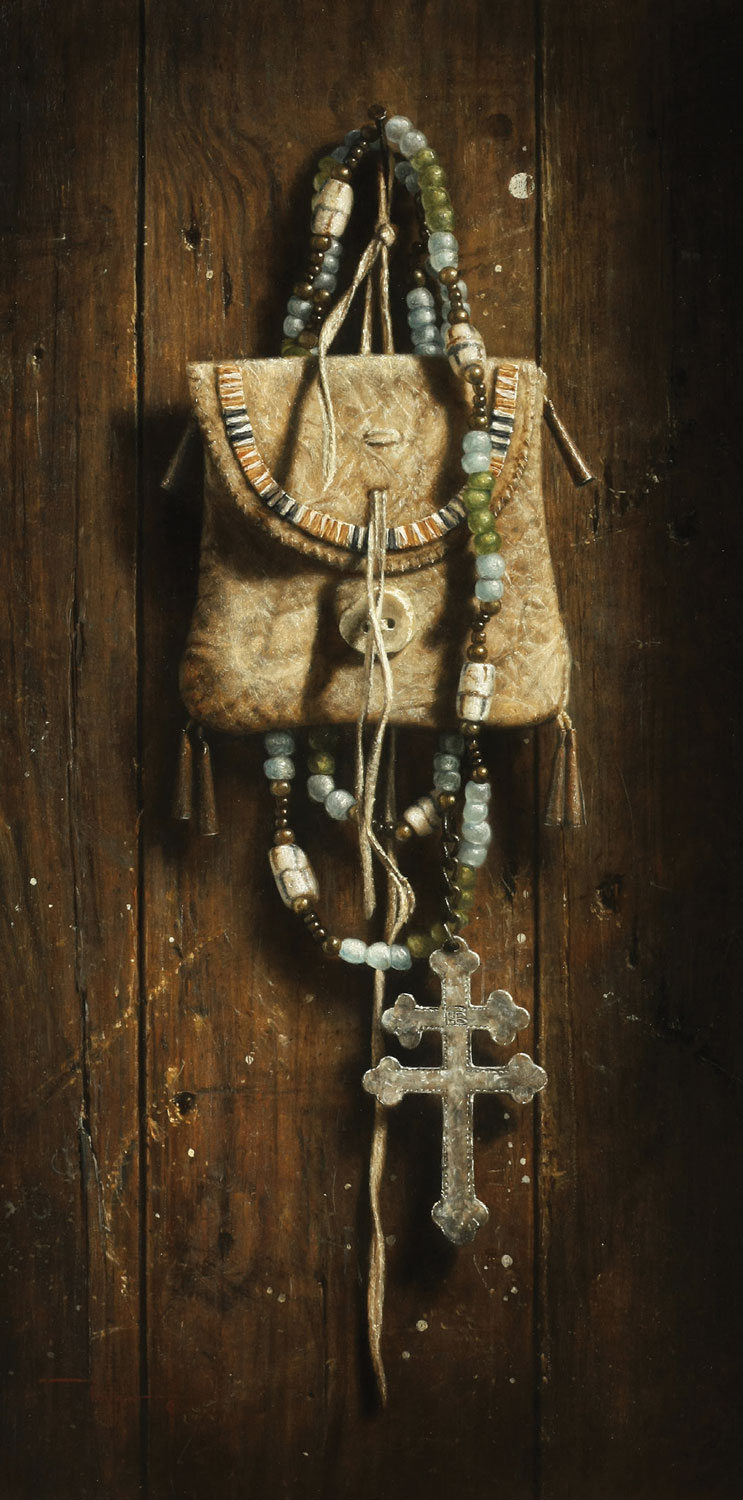

Keepsake | Oil on Canvas | 18 x 9 inches

It’s just this sort of haptic approach that raises Polzin’s work a notch above other equally talented painters working in a realistic mode. Fellow artist Luke Frazier, who collects Polzin, points out that “there’s a lot of artists out there, but [Polzin] is following his own calling and producing work that no one else is doing as well. And the number of artists out there now emulating him speaks to that.”

Given the intricate technique and fine detail in his work, it’s remarkable how quickly Polzin completes a painting once he gets the composition right. “I spend roughly three weeks per painting,” Polzin says, adding that he works steadily from morning until midnight.

But the prep work can be involved. After Polzin collects or manufactures the objects he intends to depict, he has to compose the tableau in his studio. “Then, I photograph the whole thing from various angles with different light,” he says. “With flower arrangements, this is especially important because the composition changes, obviously, as the flowers wilt.”

Polzin’s mastery of Old-World techniques (think Vermeer and Rembrandt) applied primarily to Western themes creates a unique and distinctive body of work. And Polzin is right — what better term for new world work that feels older than Americana?

Manifest Destiny | Oil on Canvas | 38 x 38 inches

Take for example Mountain Jubilee, a painting that depicts a fiddle poised against the backdrop of a Hudson’s Bay Company blanket. These two iconic elements of Westward Expansion fit together in the composition simply because of their nature, but they also reflect our romanticized sense of the conquest of a continent.

In fact, one of the most compelling elements of Polzin’s work lies in the way it evokes a nostalgia for the past as we imagine it. The power of his paintings lies in his recognition that even if much of the American past, especially our history of the westward migration, has been falsely idealized, the objects left behind — wooden cartridge boxes, the classic Winchester rifles, elaborate headdresses, old fiddles — are undeniable relics of history that connect us to our forebears, known and unknown, who once held and used these things.

Compana de Misión | Oil on Canvas | 44 x 24 inches

This is evident in a painting he created for his upcoming November 16 solo show titled Grace and Grit: An American Narrative at Legacy Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona. In Quick Draw, the ivory-handled Colt revolver and its belt of cartridges appear before a pencil sketch of a cowboy drawing his gun. It tells a clever and self-referential story, underscored by the double meaning of its title. The inclusion of what looks like an antique medicine bottle, blued by age, adds to the sense of nostalgia without falling into an anachronism. It’s a composition that encapsulates Polzin’s sense of arranging objects for a painting, and how he captures the historical past that inspired the artwork in the first place — sort of an Americana variation on M.C. Escher’s drawing of hands drawing themselves.

Some refer to Polzin’s work as “hyper-realism,” but as Brad Richardson at Legacy Gallery explains, that’s a mistake. “Kyle is a traditional Realist, working out of the trompe l’oeil tradition, which means that if it’s a painting of something hanging on the wall, then it looks like something actually hanging on the wall.” Richardson also emphasizes Polzin’s mastery of composition. “Kyle understands the power of composing the scene, choosing the objects he plans to depict, and he understands how to work the lighting. His work gives off a kind of glow, as if there’s a candle in the room that you can’t see. It’s an atmosphere akin to the Old Masters.”

Burnished With Time | Oil on Canvas | 27 x 19 inches

For an artist in his 40s, Polzin has achieved considerable success in short order. “As young as he is, he’s already among the top living artists in terms of his pieces earning the most per square inch at auction,” Richardson explains. “His numbers alone are an incredible accomplishment.” In 2014, for example, Polzin’s Mystic Warrior sold at auction for seven times more than its expected price, setting an auction record and creating a waiting list of collectors. “That really gave his career momentum,” Richardson says. “There’s really something special about his work that people respond to. He just does so many things so well in each painting.” And Frazier echoes that sentiment. “The amount of detail reflects how much he loves the subject matter — his art is close to his heart. And he’s not prolific, which is reflected in the prices. I like what he’s doing. That’s why I collect him — he’s impressed me.”

No Comments