17 Nov Leaving a Legacy

IN 1993, ALLAN AFFELDT READ AN ARTICLE in Preservation magazine that would change his life forever. In this publication was a list of the country’s most important buildings slated for demolition. La Posada Hotel in Winslow, Arizona, was one of them. Abandoned since 1957, the once-elegant La Posada was reduced to a shell, and the owners, the Santa Fe Railroad, were anxious to bulldoze and erase the eyesore from the landscape.

“I went out to look at it,” says Affeldt, a Southern California investor and history aficionado. “Then we bought it in order to save it. Turns out it was a masterpiece of one of America’s most important architects, Mary Colter.” Four years later in 1997, La Posada — a prime example of Spanish Revival architecture — was restored to its former glory and reopened for guests, complete with bucolic landscapes, original Southwest works of art and a fine-dining restaurant.

Today, thanks to the efforts of Affeldt and others, Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter [1869–1958] is finally receiving credit as the architect who pioneered Southwest architecture by being the first to incorporate Hopi, Zuni, Navajo and Mexican motifs in her structures. The cutting-edge Colter designed many buildings in her more than 40-year career, serving as the principal architect behind the glamorous train depots and hotels along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway lines at a time when women were unknown to the profession. She was also responsible for creating the majority of the structures and lodges in the Grand Canyon. In fact, many praise Colter for her use of raw, natural materials, a signature design element of National Park Service rustic, or “parkitecture.”

According to the Fred Harvey biography by Stephen Fried, Appetite for America, from 1902 to 1948 Colter worked for the Fred Harvey Company, and she became the company’s chief architect and designer in 1910. In his book, Fried counts at least 21 landmark hotels, commercial lodges and public spaces birthed by the prolific architect.

Progressive to the extreme, Colter was one of the first to explore the role of tourism architecture and making places feel comfortable for guests, says Barbara Felix, the architect who oversaw the restoration of La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe, New Mexico, another Colter project. “We take that for granted now, but it was pretty forward thinking in the 1920s,” Felix says. “She influenced what we think today about the Southwest. She helped romanticize the West and made it feel safe and romantic.”

As the story goes, the Fred Harvey Company lured tourists to the American West for the first time by offering fantastic meals at the train depots. The Steve Jobs of his era, businessman Fred Harvey dared to “think different.” Prior to this clever plan, the food in the train stops was expensive and barely edible. It didn’t take long for the Fred Harvey Company to blossom beyond the owner’s wildest Western dreams. After Fred died in 1901, his son, Ford Harvey, contributed his efforts towards the enterprise’s meteoric rise, adding more depot food outlets and retail stores.

Soon, statement hotels were added to the portfolio. Harvey House hotels were the first built in the Grand Canyon. These include the iconic El Tovar, Bright Angel Lodge and Phantom Ranch, which all remain in operation today.

For El Tovar, the company hired architect Charles Whittlesey, but Colter was assigned to design and furnish the interiors. She also worked as lead architect in designing eight other Grand Canyon buildings in her signature Southwest style. These included sites such as Phantom Ranch, a lodge at the bottom of the canyon accessible by hike, mule, raft or helicopter. Another structure, Hopi House, made of sandstone, was modeled after a traditional Hopi dwelling where windows are small and few. In the Grand Canyon, signage and brochures now hail the woman who possessed no formal architecture degree.

Back in the early 1900s, with many of its holdings in the Southwest, the Fred Harvey Company also acknowledged the vitality and value of Native American art. Working with the tribes, it sold authentic jewelry, rugs, baskets and other wares in its gift shops. The firm decorated the hotels lavishly with Southwest artifacts. Says Daggett Harvey Jr., Fred Harvey’s great-grandson, “I think [Ford] was one of the first to do that. No one else took Indian jewelry and sold it to whites. The buyers would go to the reservations and tell them what to make and sell. It was good for the consumer, and it was good for Indian culture.”

The company, deep into the tourism promoted by Ford’s administration, brought visitors to reservations on its “Indian Detours.” The enterprise curated its own Indian museum and hired Native Americans to weave blankets and demonstrate other types of artistry. Today, the museum art collection is scattered, but much of it can be found in the Phoenix Heard Museum, which is currently featuring the exhibit Over the Edge: Fred Harvey in the Grand Canyon and in the Great Southwest, through December 31, 2017.

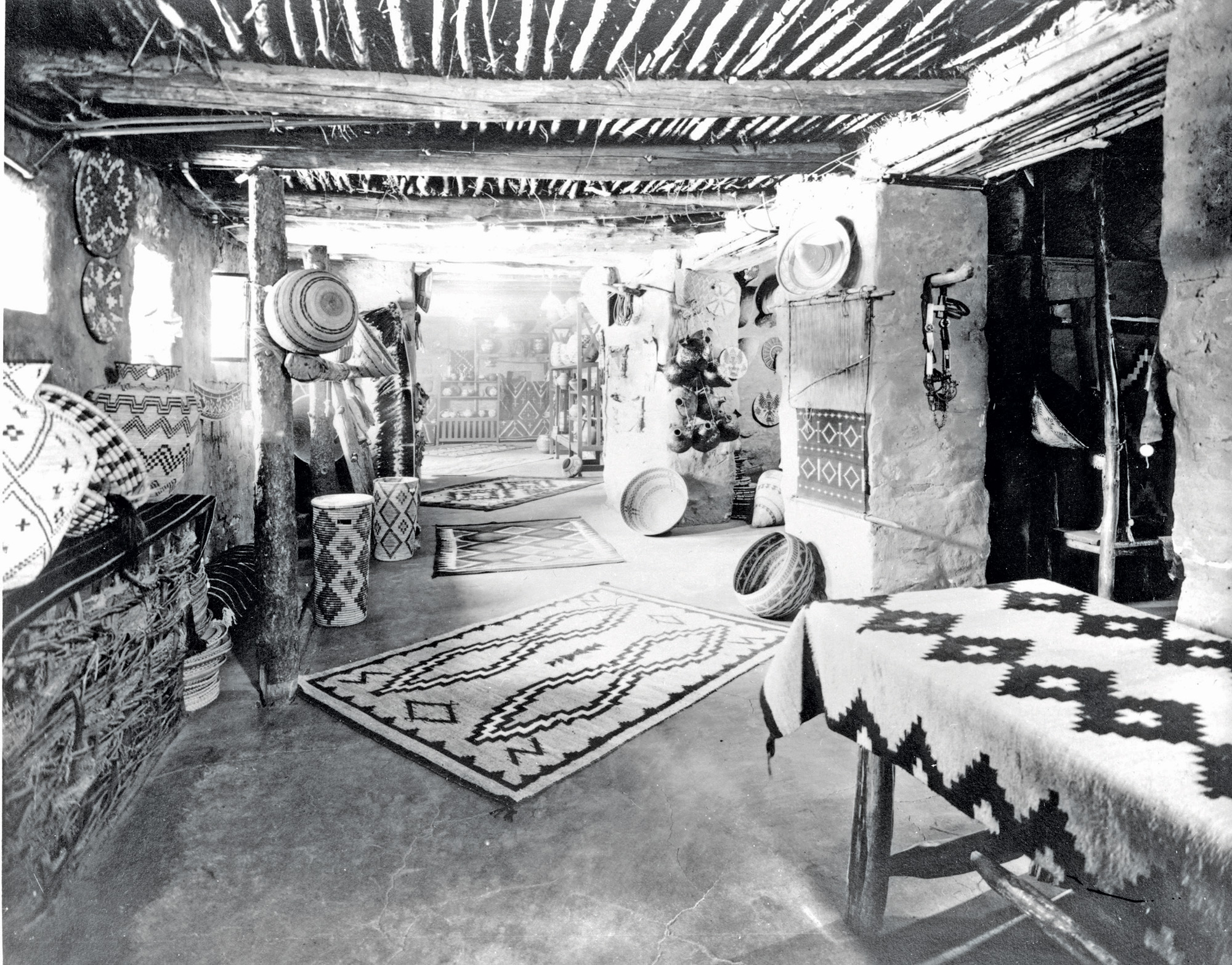

In fact, Colter’s first solo assignment was to create the Indian Room, a store inside the now-defunct Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque, New Mexico. It was the first time Native American handiwork was sold as fine art, not souvenirs. The baskets, hand-woven rugs, jewelry and art pieces were displayed in an elegant fashion.

“It was the first time anyone gave people the idea that you could take Native American art and show it off in their first and second homes. She was able to design the room and show how to make sense of all the artwork and pottery and textiles,” says Diana Pardue, curator of collections at the Heard Museum.

Felix, of the firm Barbara Felix Architecture + Design, adds that Colter proved that the West was a place “where you could go and meet Native American artists in person, take artifacts back home and have a story to tell your friends.”

Sadly, the Harvey dynasty came to an end after two world wars and a severe drop in passenger train travel. In 1968, the family sold holdings to Amfac Corporation, now renamed Xanterra Parks and Resorts. The 92-year-old company said goodbye to its newsstands and gift shops across 80 cities. Customers and world leaders would fondly remember the food at Harvey’s 100 restaurants and the hospitality at its hotels.

Original Fred Harvey enterprises no longer bear the company name. Many of the depot buildings and hotels, except for the Grand Canyon properties, have been leveled. Thanks to folks such as Affeldt, who believe old buildings are worth preserving, several Harvey hotels have been rescued, such as La Posada in Winslow; La Fonda in Santa Fe; and La Castaneda Hotel in Las Vegas, New Mexico, which is also owned by Affeldt and is awaiting restoration.

La Posada’s general manager, Kristi Ulibarri, is a fourth-generation employee. Her great-grandmother was a Harvey Girl waitress at the hotel. The Harvey Girls were single women who headed west to work in Harvey’s hotels. More than 100,000 single women served as Harvey Girls during the company’s history, and it’s said they tamed the Wild West. Today, Harvey Girl clubs thrive in the communities where they worked. At La Posada, Harvey Girls and their descendants give tours, donning white pinafore aprons atop black skirts and blouses.

Ulibarri’s great-grandfather was a railroad worker who also built a former Harvey restaurant at the train depot across the street from the hotel. “Anyone who grew up in Winslow knows about La Posada,” she says. “I love working here. It is very cool to be operating in the same building as my great-grandmother. I hope that anyone staying here will feel like they have been transported back in time.”

La Posada bills itself as “the last of the great railroad hotels” and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The rooms from 1929 speak of the good ol’ days with pine beds and hand-woven Zapotec rugs, Mexican tin and Talavera tile mirrors and cast iron tubs. Each of the 53 hotel rooms is named after a famous guest — Albert Einstein, Judy Garland, Howard Hughes.

Fried’s book, published in 2010, is considered the definitive treatise on all things Fred Harvey. History buffs use the book as a roadmap to retrace where the depots, hotels and restaurants once stood. In 2013, independent filmmaker Katrina Parks premiered her PBS documentary, “The Harvey Girls: Opportunity Bound,” launching a hunger for more of the Fred Harvey tale.

Because of the recent book and film, Fred Harvey’s great-grandson, Daggett Harvey Jr., of Chicago, Illinois, confirms a resurgence of interest concerning his family and the role the company played in forming the American West. He has fielded more requests for interviews and speaking engagements on family history than ever before. “I am very proud of this legacy,” he says. “The Harvey Company was forward thinking, held high standards and its insistence on quality and the way they treated employees was ahead of its time. I think they were enlightened.”

Formerly the company’s director of personnel, Harvey Jr. stresses that Fred possessed a business acumen and a curatorial eye that was extraordinary. Early in his teen years Harvey Jr. appreciated the beauty of the lodges the family managed at the Grand Canyon.

He also appreciates La Fonda Hotel. The Spanish Colonial National Landmark hosts tours four times a week. The docents lead guests and local groups through the public areas of the hotel, pointing out the artwork, furniture and motifs indicative of Colter’s whimsical style. Truly artistic, she even designed the china on the Super Chief passenger train.

According to Jayne Weiske, the hotel’s director of marketing, Colter commissioned a 30-inch-high metal rabbit ashtray affectionately named Harvey. It’s so popular that the hotel sells miniature Harveys in the gift shop. “Her style was kind of fun, and she was not afraid of being modern,” Weiske says.

Colter wanted her work to look as authentic as possible, notes Felix, who says she would take new fabrics and have her employees walk all over them to produce an aged appearance. “She was very gritty in her architecture and her style. She went into great detail even in mixing her own plaster colors and working with tin artists. She makes the rest of us look like we are sleeping on the job,” Felix says.

When Ford Harvey hired Colter, he did not care that she did not have an architecture degree. (She did attend the California School of Design.) He also did not care that she was a woman. “The Fred Harvey Company was gender blind,” says Affeldt. “The company let her be an architect and do the work.”

During her era, architects favored European styles, but Colter recognized the Southwest had something magical to offer, Affeldt observes. In believing in her vision, the Fred Harvey Company was able to leave behind a legacy of landmarks unique to American history. “She was totally radical and a wonderful architect,” he says.

- Hopi House represents one of eight Mary Colter buildings at the Grand Canyon and is also a National Historic Landmark. Colter loved to imagine her buildings as backdrops for fictitious characters and stories. In designing and building the famous Hopi House on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, she envisioned an authentic Hopi dwelling that a family might have lived in during the 16th or 17th centuries. Photo: Mike Quinn, NPS

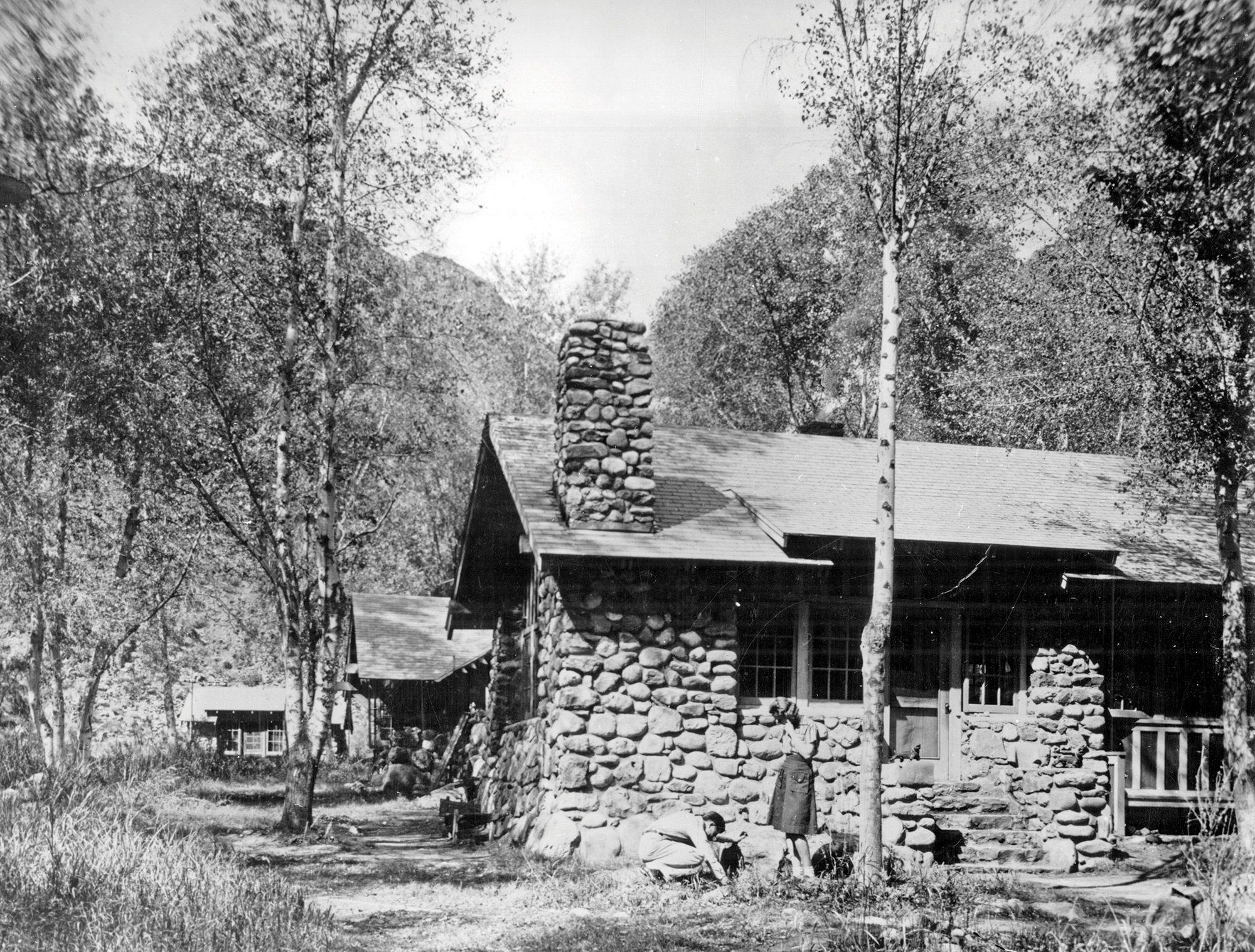

- Phantom Ranch today is typically booked unless reserved more than 13 months in advance. Photos: NPS

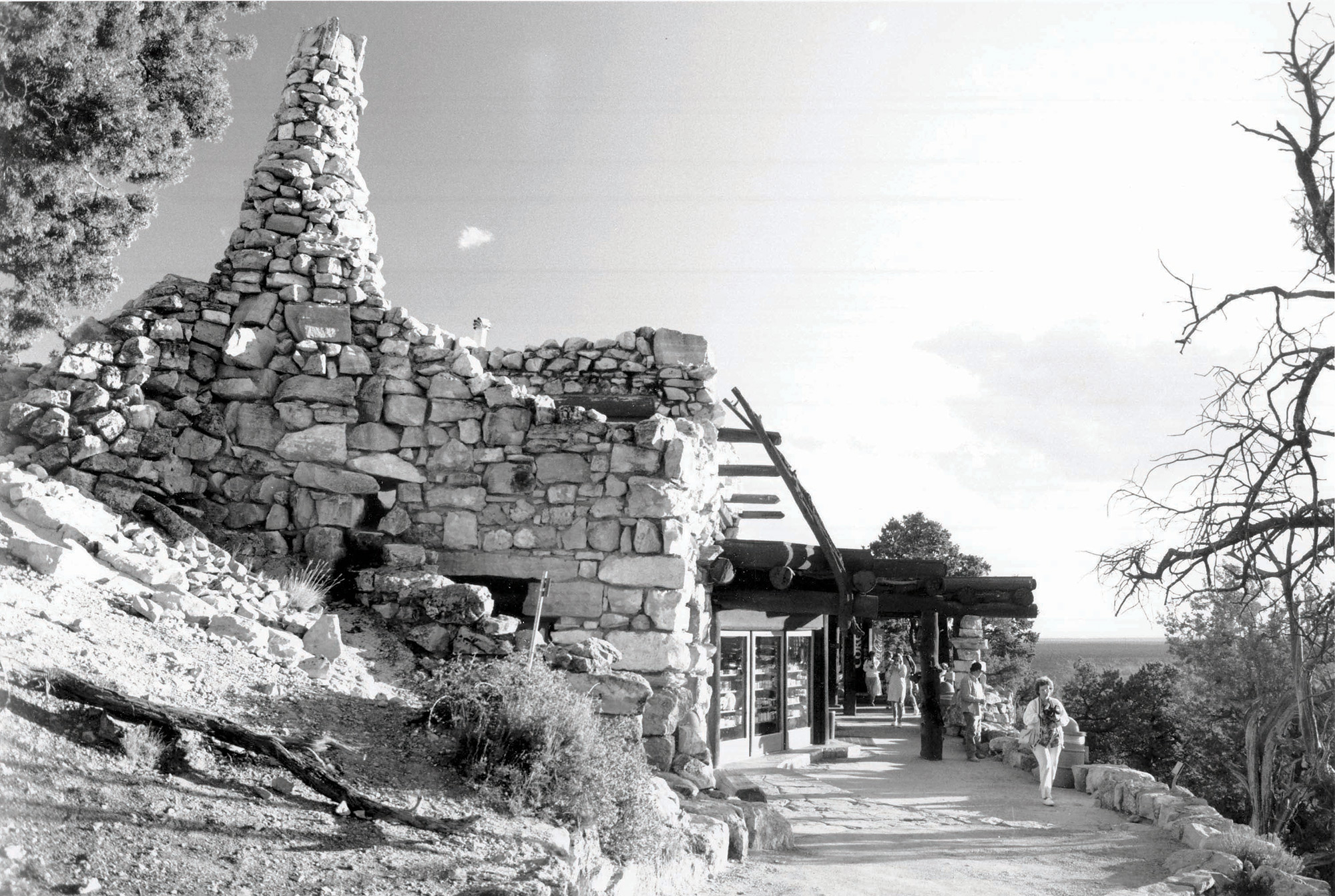

- The Grand Canyon’s historic Desert View Watchtower reaches 70 feet and was built in 1932 as a four-story structure.

- The west-facing side of Hermits Rest, built in 1914, was originally a rest stop for tourists. Photo: Mike Quinn

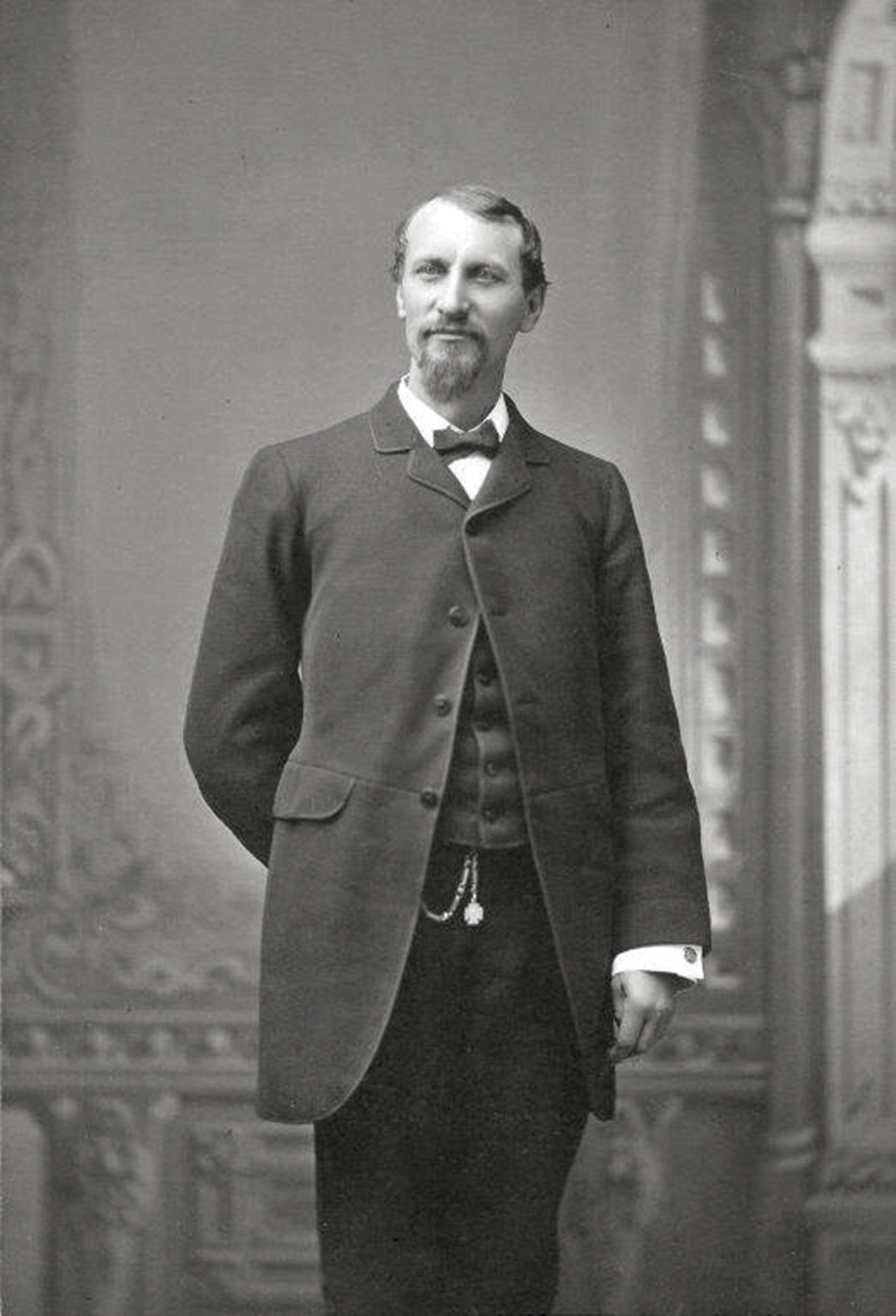

- Fred Harvey as a young man, courtesy Stephen Fried.

- Mary Colter, age 50 in this photo, was known as a determined architect with great taste in all types of design. Photo: NPS

- Hopi House was created for Fred Harvey as a concession stand where Native Americans made artifacts to sell on site. Shown here is the Nampeyo family, circa 1905. Photos: NPS

- The Phantom Ranch guest lodge, circa 1950, at the base of the canyon, was a challenge to reach.

- The Lookout Studio at sunset maintains its authentic charm today. Photo: Mike Quinn

- The Grand Canyon’s historic Lookout Studio, circa 1915, by Mary Colter served as a pivotal location where visitors could see brave hikers and mule riders descending the canyon.

- The interiors of the Hopi House (circa 1905) were comprised of rugs, baskets and other treasures made by local Native American tribes.

- Today, the Watchtower still stands sentinel over the park after undergoing major renovations in 2010. Photos: NPS.

- Hermits Rest at the Grand Canyon (pictured here in 1987) was created to resemble a natural stack of rocks on the landscape. Photo: NPS

- La Fonda is a historic landmark on Santa Fe’s Plaza.

- The retired Harvey Girls now give tours of the property.

- La Posada’s fully restored ballroom is ready for visitors. Photos: courtesy La Posada

No Comments