02 Mar Loud, Free and Ever More Beautiful

“IT TOOK ME FOUR YEARS TO PAINT LIKE RAPHAEL, but a lifetime to paint like a child.” — Pablo Picasso

Citing the words of Picasso, Mark English strives each day to paint like a child — with freedom and abandon. For someone with more than 50 years of award-winning illustration and fine art experience, this can prove to be a more difficult feat than you’d expect.

“My theory about art is that it’s a lifetime search,” says English, now in his early 80s. “My work continues to develop as I keep learning. I always tell my students that if they’re bored, then they need to look for something new. I keep doing it because I’m still having fun.”

His bold colors, uniqueness and mystery attract collectors, but that’s not surprising to the galleries who represent him. “What is wonderful about Mark’s work is that he has such broad appeal,” says Will Thompson, owner of Telluride Gallery, which has been representing him since English became a full-time painter. “We have sophisticated collectors who love his work, and so do people who suppos- edly don’t know anything about art. He knows how to grab the viewer — a skill that transferred over from his illustration days.”

After growing up in Texas, where he spent his youth drawing, English was drafted into the Army where he met Robert Benton and Harvey Schmidt, well known in the 1950s for their work at Esquire. They introduced him to the idea of becoming a profes- sional artist and suggested he study at Art Center College of Design in California.

Upon completion of his military service, English did just that and, after majoring in advertising illustration and taking every drawing class he could, he graduated and received an offer to work for N.W. Ayer & Son advertising agency in the company’s Detroit office. One year later, he started working at Art Staff, where he honed his craft and became a true illustrator. When after three years he wanted to go beyond creating car illustrations in Detroit, English moved to Connecticut in 1964 with his young family: his first wife, Peggy, and children Donna, Stephanie and John.

The East Coast art world was tougher to break into than English had anticipated and initially assignments were scarce. But he believes this period of unemployment played a critical role in his artistic development as he used the time to learn to paint in a way that Art Center College had not taught him — by studying the work of such artists as Bonnard and Vuillard at New York museums. English found his first agent, Tom Holloway, and began illustrating for a variety of magazines.

His first big break finally came in 1965 when Reader’s Digest hired him to create a dozen illustrations each for two books: Little Women and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Four of those works won medals presented by the New York Society of Illustrators and were featured in the Annual of American Illustration that year. The awards repre- sented the first of many English would receive from the society throughout his career. In fact, English became the most awarded illustrator in the history of the Society of Illustrators and was elected to its hall of fame in 1983, where he joined the ranks of N.C. Wyeth, Norman Rockwell and Maxfield Parrish, among others.

English worked nonstop for the next 25 years, completing illustrations for a variety of clients, including Good Housekeeping, Sports Illustrated, Time, Atlantic Monthly, the U.S. Park Service, IBM and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, as well as the U.S. Postal Service, for whom he created 13 stamps.

In 1977, an offer from Hallmark Cards brought him to Kansas City, where English served as artist-in-res- idence to its creative staff. Although he had originally intended to stay just a year, English established a life in Kansas City, continuing freelance illustration for a growing number of clients while simultaneously cultivat- ing a painting style on which he would eventually focus full time. He felt the need to “explore what the difference was between the two and figure out what I could offer as a painter.”

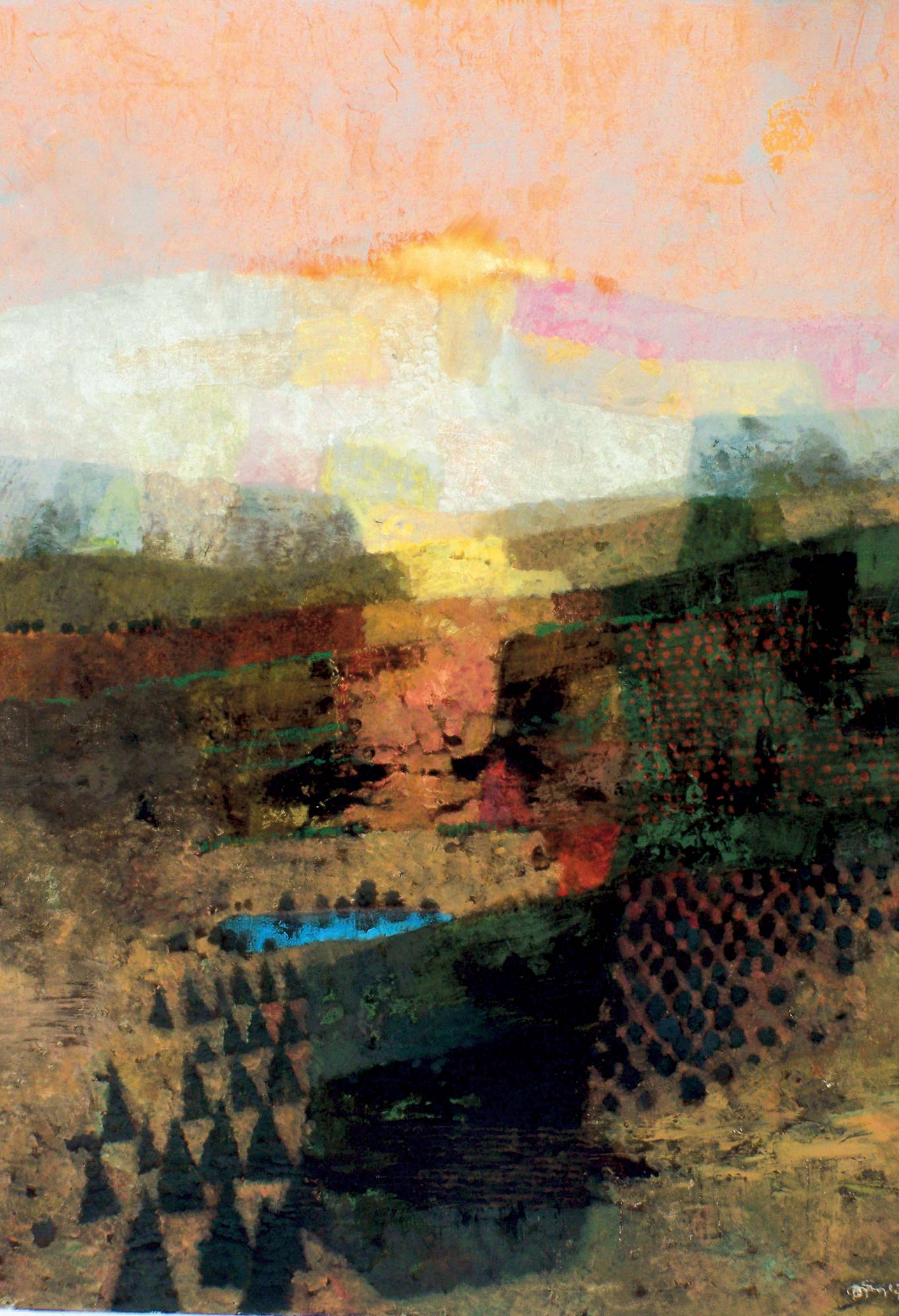

Mark, and his second wife, Wendy, moved to a renovated farmhouse in Kearney, Missouri, in 1983 where, for a while, he continued to keep a foot in both the illustration and fine art worlds. By the early 1990s, English felt ready to focus exclusively on fine art and pulled together a body of work for his first one-man show. Beautifully patterned, these early paintings are abstracted landscapes, mostly of farm- land, created from his imagination.

“I was very calculated with my work as an illustrator,” English says. “I wanted to have much more freedom and experience lack of control to see where it took me. I wanted the viewer to study my work and find the story in the painting.”

That desire for freedom led to a process English still employs today. He composes each painting by creating multiple thumbnail drawings, think- ing through and refining the idea of what he plans to paint. However, when the idea transfers to a larger format, it may evolve as he chooses his color palette and establishes the mood.

“His bold colors, uniqueness and mystery attract collectors …”

English finds inspiration every- where and attributes some of his explorations to “happy accidents.” He tells the story of how one afternoon he came across his youngest daughters, Emily and Sarah, cutting letters out of construction paper. He took the color- ful negative shapes back to his studio where he glued them onto a board and covered them with roofing tar. He then scraped away the tar until the color started to reappear, finally painting back into it. This new “accidental” technique inspired him to create a series of 12 to 15 paintings.

“No one else is doing what he does with mixed media,” says Weinberger Fine Art owner Kim Weinberger, who has represented English since 2010. “One of the beauties of his work is that it doesn’t come from a picture, but rather his memories and dreams. For example, in a figure piece, you don’t clearly see the face, so it’s up to the viewers to find it and create their own feelings about the piece.”

It’s this mystery that intrigues both English and the viewer.

Fellow artist, teacher and long- time friend, Meredith Wilson, wrote of English’s work: “… The work of an art- ist can touch the core of a person in a way that defies explanation — the way a song can break your heart. And so it was with Mark’s work then, and is with his work now as he continues to grow as an artist. Mark’s song just becomes louder and more beautiful.”

- “Pegasus” | 60 x 48 inches

- Mark English in his studio

- “Another Pink Sky” | Mixed Media | 42 x 30 inches

- “Ocean View” | 30 x 24 inches

- “Yellow Hat” | 58 x 50 inches

- “Bell Tower” | 44 x 30 inches

- “Milk Maid” | 48 x 24 inches

- “Landscape 33” | 48 x 48 inches

- “Blue Runaway” | 32 x 42 inches

No Comments