06 May Making Their Mark: American Women Artists

“TO CREATE ONE’S WORLD IN ANY OF THE ARTS TAKES COURAGE,” observed Georgia O’Keeffe, speaking from experience. A supportive community and some exposure can help, too. American Women Artists (AWA), a membership organization established in the early 1990s, seeks to foster both with 25 in 25, an initiative that launched in 2017 to secure 25 museum shows featuring exclusively female artists in the span of 25 years.

Poder | Natalie Dark | Colored Pencil on Paper | 30 x 22 inches

The organization was founded in response to the statistic that women artists make up only 3 to 5 percent of permanent holdings in U.S. art museums. The Booth Western Art Museum is scheduled to host the fifth exhibition, Making Their Mark: American Women Artists, this summer. This juried event will feature nearly 100 paintings and sculptures by AWA members.

Allure of Kimono | Carla O’Connor | Watermedia | 30 x 22 inches

“You only have one life to live, and when you are given a gift, you have a responsibility to … explore that gift fully,” says Natalie Dark, one of the show’s participating artists. Dark bravely leapt from a successful career in market research to devoting herself full time to her art. Her lush, botanical works, rendered entirely in colored pencils, radiate the contemporary influences of her Cuban-American cultural heritage and Miami roots, with echoes of the Dutch masterworks in their sumptuous black backgrounds.

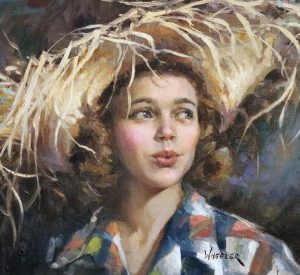

Spirit | Kathie Wheeler | Oil | 13 x 15 inches

“The black backgrounds weren’t intended to be a play on the Dutch Masters,” Dark explains. “They came from a desire to make art that felt like me because I couldn’t find that art anywhere I looked … art that represents the full range of emotions I feel … deep, dramatic, rich, and powerful.” At first, she tried to capture these feelings by other means, because the black “felt so scary. It was such a commitment to go full black in colored pencil. So I tried lots of other things … but eventually, there just was no other way. I bit the bullet.” Dark’s bold choice brought vital, vibrant results. “My work instantly expressed the exact emotions I was feeling and wanted to communicate to the world.”

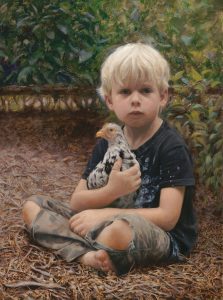

Camouflage | Kathy Morris | Oil | 18 x 24 inches

Communication has also been a key influence on painter Kathy Morris, who has an oil portrait in the show. Morris lost most of her hearing in early childhood. She became adept at understanding others through visual means: “The necessity of intensely focusing on faces in order to read lips and hear causes me to be extremely visually aware and attentive to detail — alert to the nuances of people’s facial expressions, their mood, emotions, and body language.”

Leaning Into the Sun | Sally Painter | Oil on Canvas | 18 x 24 inches

These nuances shine in her portraits, many of which feature “those I love,” she explains, “[and] to whom I have a deep emotional connection.” The young faces that look out from Morris’ paintings belong to her grandchildren, who are refreshingly portrayed with all their real-life moods and without sentimentality. “Children have the same range and complexity of emotions as adults,” Morris says. And while there’s a story behind each painting, she likes honing in on small, seemingly commonplace fragments of time. “The extraordinary resides in everyday life events. I’m capturing moments as a visual journal of the everyday lives of my children, grandchildren, and friends.”

Smalltalk | Debbie Korbel | Mixed Media | 67 x 70 x 24 inches

Debbie Korbel, who has a sculpture in the exhibition, is interested in people, too; she portrays them — loving, kissing, dreaming, flirting, praying, and metamorphosing — in her surprising pieces. But she also brings an array of equally spirited animals to life, including horses. “My first crush was a horse!” she says. “Need I say more?” Her girlhood interest was renewed when she became a mom. “When my daughter was young, she took riding lessons, and … I found [horses] as beautiful as ever. They had lost none of their magic to me.”

Workin’ Girls | Ginger Bowen | Oil | 18 x 30 inches

Magic is an apt word for the essence of Korbel’s works. “I try to make artwork that I would like to see — something that I haven’t seen before, and I especially like artwork that makes me laugh.” Born through a synthesis of skill and spontaneity, her sculptures are often sparked by an evocative found object. Korbel’s sculpting process is as organic and playful as her finished work. “I don’t make maquettes or … elaborate sketches prior to starting the project. The sculpture evolves,” she says, “as I am working on it. I like to be surprised, too.”

Imagining | Cynthia Feustel | Oil | 34 x 16 inches

An organic quality — serene and deeply attentive — also characterizes the work of Julie Davis, a plein air artist who will have a painting in the Booth show. Instead of predictable, picture-postcard landscapes, Davis captures unshowy scenes from the natural world and abandoned buildings visibly yielding to the effects of time. And she illuminates something profoundly moving in these subjects. “I find the most character in structures that nature is reclaiming, where humanity and nature intersect,” she says. “The buildings we live, work, and play in, and the landscape that surrounds us, are part of our cultural story and are a present, tangible representation of our history.”

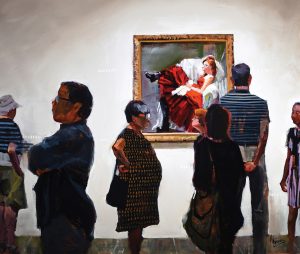

A Common Language | Heather Arenas | Oil on Cradled Birch | 30 x 36 inches

Sometimes, Davis’ plein air process is one of information gathering, and she finishes some pieces in her studio. Even so, a sense of raw, immediate beauty persists. “I hope that my deep respect for nature comes through in my work. … We move so quickly in our society, I want others to pause and reflect on the stories behind our environment and value not just the new, but how the old and worn is woven into the fabric of who we are.”

Leaning Toward the Past, Marfa | Julie Davis | Oil on Panel | 18 x 24 inches

View the work of these artists and many others at the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, May 27 through August 23.

No Comments