10 May Modern – Day Saints Artist Arthur López Brings Tradition to Life

DURING THE 17TH CENTURY, as the Spanish conquistadores roamed what is now the American Southwest, they found themselves lacking something of importance. Though devout Roman Catholics, they hadn’t brought along the iconic religious statues central to their worship (baroque statuary is cumbersome and heavy). So they did what any resourceful devotee would do: They improvised. Carving figures out of aspen and pine, and taking materials and techniques from indigenous communities, they created rustic santos, stand-ins for the ornate versions back home.

La Asuncion de Maria | Hand Carved and Painted Wood Heart | 18 x 10 x 3.5 inches

So began the 400-year-old tradition of the santero, woodcarvers who create sculptures of saints and other holy figures. While santeros exist in many regions of the world subjected to Spanish rule, the culture remains particularly vibrant in New Mexico, where they carry a recognizable regional signature.

“If you look at a New Mexico santo, it has a very distinct look, almost like folk art,” says Arthur López. And if anyone should know, it’s López. Renowned worldwide as one of Santa Fe’s preeminent woodcarvers, he was awarded the 2019 United States Artists Fellowship in Traditional Arts for his superlative — and surprising — interpretation of this art form.

Unlike many in his field, the skill wasn’t passed down from older generations. Instead, López came to it after a decade-long stint in graphic design, and he may never have found his calling had it not been for an unexpected turn of fate in the late 1990s.

“I was working in Los Angeles and had just accepted a job offer in New York. I was going to stay in Santa Fe with family in between, and the day I got to town, my father was diagnosed with cancer,” he says. “I turned down the job in New York so I could stay and help care for him.” His father passed three months later, but the stint in Santa Fe rekindled López’s lifelong passion for making art.

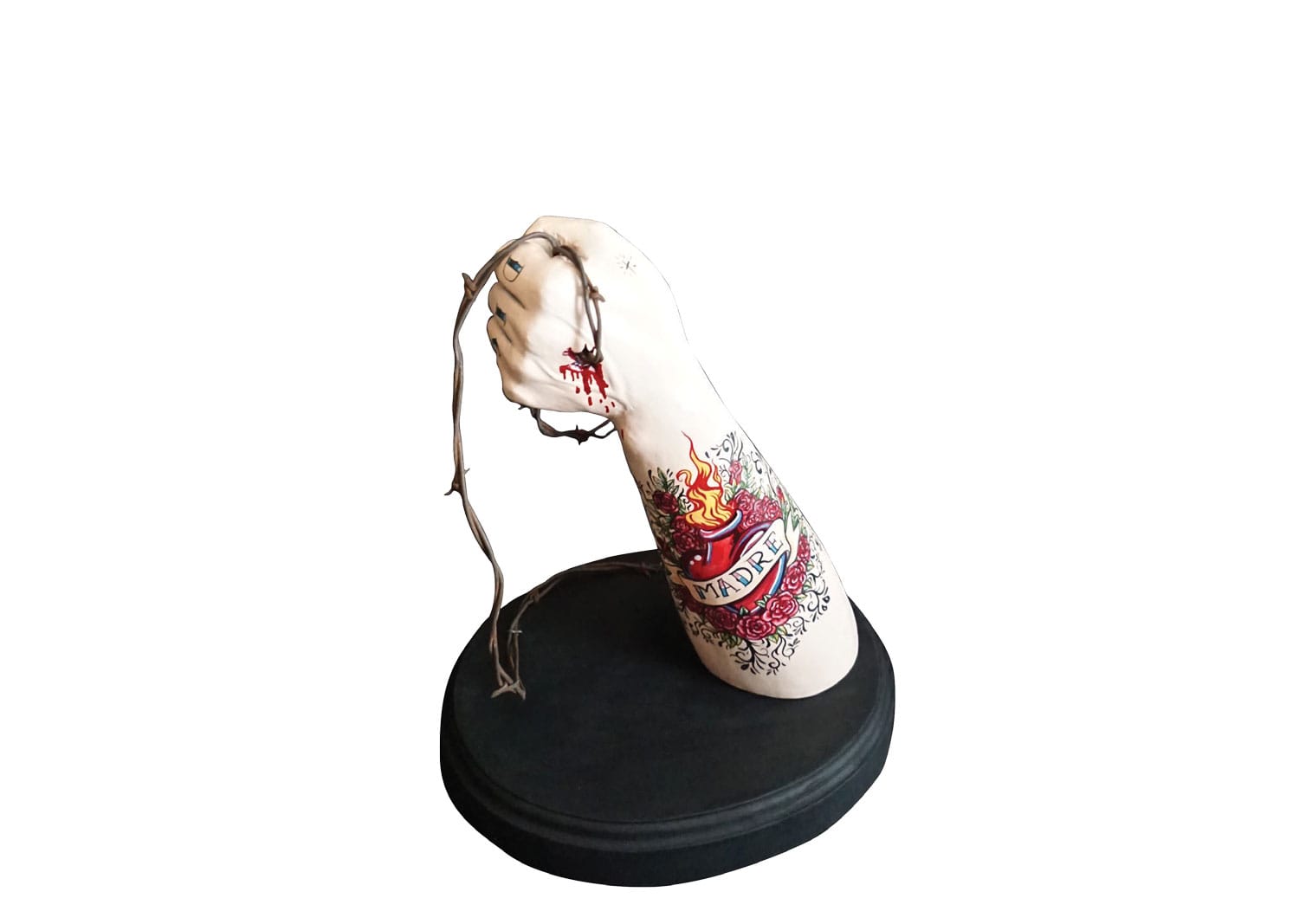

La Asuncion de Maria | Hand Carved and Painted Wood | Hand: 14 x 10.5 x 8.5 inches | 2019

“For whatever reason — I think something to do with my dad — I was really drawn to the imagery at the Spanish Market, so I went to see if I could learn how to do retablos [two-dimensional carvings of saints]. But then I saw the three-dimensional carvings, the bultos, and thought, ‘I think I’d rather do that.’”

Santa Lucia | Hand Carved and Painted Wood | 21 x 13 x 8 inches | 2017

Although he grew up drawing and painting, López had never tried carving before. But, he says, “For whatever reason, it came to me more naturally. I was completely overtaken with my desire to do three-dimensional work. I started going to every show, down to the archives of the Museum of International Folk Art, doing as much research as I could.” The rest, as they say, is history. Six months after he carved his first bulto, López was juried into the Santa Fe Spanish Market. And the Museum of International Folk Art purchased one of his first pieces. And ever since, he’s been working as a full-time artist, gaining notoriety.

Although he grew up drawing and painting, López had never tried carving before. But, he says, “For whatever reason, it came to me more naturally. I was completely overtaken with my desire to do three-dimensional work. I started going to every show, down to the archives of the Museum of International Folk Art, doing as much research as I could.” The rest, as they say, is history. Six months after he carved his first bulto, López was juried into the Santa Fe Spanish Market. And the Museum of International Folk Art purchased one of his first pieces. And ever since, he’s been working as a full-time artist, gaining notoriety.

“For him, to have started working and immediately become an internationally shown artist, with exhibitions in Japan and in Germany, that’s saying a lot,” says Cyndi Hall, associate director of Manitou Galleries in Santa Fe. “Yes, he’s brilliant at what he does. Yes, he’s pushing all the boundaries in this medium. But at the end of the day, this is a God-given talent,” she says.

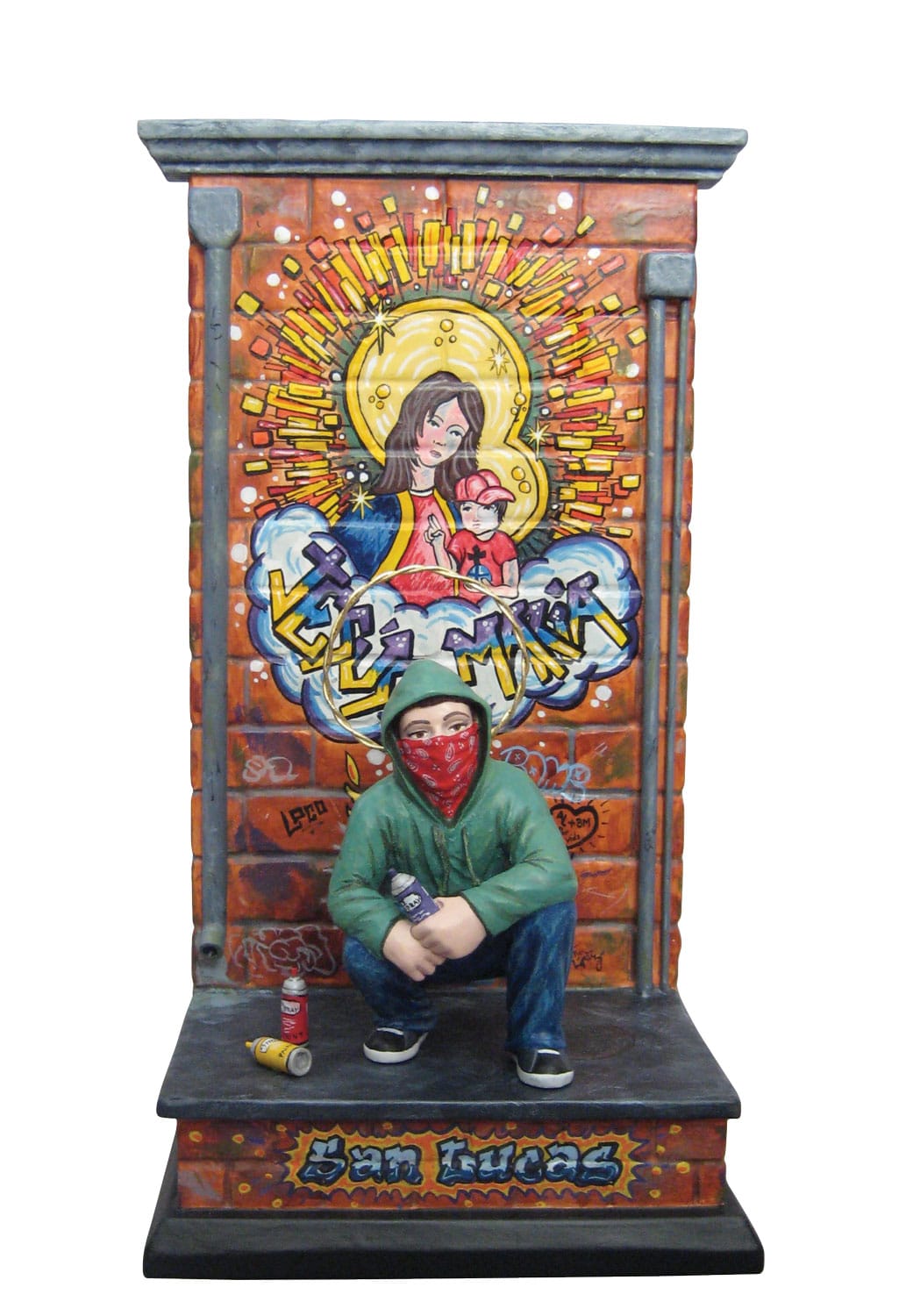

Wall Bangin’ San Lucas | Hand Carved and Painted Wood 15.5 x 9.5 x 6 inches | 2011

While his precipitous rise to stardom is noteworthy, it’s perhaps not the most intriguing thing about López and his work. “He’s a great example of an artist who’s straddling that line between traditional and modern,” says Jana Gottshalk, curator of the Museum of Spanish Colonial Arts in Santa Fe. López is dedicated to working with historical materials — making pigments out of cochineal beetle and black walnut, mixing gesso out of rabbit-hide glue and marble dust — and remains devoted to the signature New Mexican santo style. Yet, while many santeros stick to traditional imagery, López goes off script more often than not, transposing the narratives of saints and holy figures into contemporary settings. “I like to throw some humor in it, while still using some of the iconography. Each saint has their own story; I just make it more relevant for today,” López says.

It Is As It Was | Hand Carved and Painted Wood 25.625 x 18.875 inches | 2004

He gives the example of Saint Lucas, the patron saint of artists. “He’s often portrayed in the same guise, where he’s always painting the Virgin Mary. It’s so stagnant.” Instead, he’s done several bultos of Saint Lucas; in one, he appears as a graffiti artist, and in another, a tattoo artist. He’s portrayed Saint Michael, known as the slayer of Satan, as the driver of a monster truck, crushing the devil beneath his wheels. In a piece called Holy Rollers, Jesus drives a hippie-esque VW bus with all 12 apostles aboard.

He attributes this impulse in part to his upbringing. Raised in a Catholic family, attending church every day, López was exposed to graphic iconography. “The religious imagery was definitely terrifying. Looking up at the bleeding Christ, and all these figures peering down at you,” he says. When López had kids of his own, they resonated more with his creative, modern pieces than with traditional images. The same, he surmised, would hold true for all viewers: Recognizable context humanizes saints. And, by disassociating the character from traditional iconography, he provides an inroad for viewers, even those who aren’t religious. “I like the idea of someone looking at the art for what it is — which is artwork. If you’re not religious, or if you are any other faith, you can sit back and say, it’s OK to own one of these as a piece of artwork and appreciate it as such.”

One example, Hall says, is López’s piece El Niño Perdido, which depicts a milk carton with the familiar lost child photo on the back — except that it shows the Santo Niño, patron saint of travelers. “He could have just done a carving of Santo Niño, but no, he places it within an image we recognize from our childhood. He grabs the viewer, and he doesn’t let go,” she says.

And while López often uses humor to engage viewers, he doesn’t shy away from serious subjects either. “He’s not afraid to put political statements into his art, about things that he’s passionate about,” says Hall. In It Is As It Was, he depicts a single mother, a gay couple, an altar boy, and a Holocaust survivor, among other figures, beneath the balcony of the Vatican. The Pope stands on the balcony, his back turned to the crowd. “It’s really interesting. When the santeros first started, the Bishop didn’t condone their work at all. Now, here’s this guy doing this traditionally Catholic art form, and speaking out against the church and these real social problems we’re ignoring,” says Hall.

“Divine Pastures” El Nino Perdido | Hand Carved and Painted Wood 18 x 9.25 x 9.25 inches | 2013

It’s these threads throughout history that make the tradition of the santero so vibrant, and it’s López’s desire to elevate that tradition to the status of fine art — while also making it human and resonant — that makes his work especially striking. Perhaps this is in part because of the origins of his own inspiration, and the fact that the work has always been intensely personal to him: “Everything happens for a reason, good or bad,” López says. “Without what happened to my dad, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now. I was brought back full circle to my art.”

No Comments