04 Aug Monuments Man

PAUL MOORE MAY VERY WELL BE THE MOST VERSATILE and prolific figurative sculptor working in America today. During the past two decades, he has completed what many artists might consider a lifetime of work, much of it monumental in scale. Dozens of subjects — cowboys and Native Americans, presidents and athletes, governors and congressmen, doctors and educators, generals and philanthropists and more — have stirred Moore’s creative impulses. In fact, he may be the only sculptor ever to have produced likenesses of both a cartoonist and a librarian.

When the Oklahoma City native snapped a picture of James Earle Fraser’s mammoth sculpture, The End of the Trail, on a family visit to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in the early 1970s, he recalls imagining one day creating such a monument. What then seemed a far-fetched dream, is now just a day at the office for this talented artist. With an impressive list of commissions that ranges from life-size busts to larger-than-life, multifigure memorials, scattered from Massachusetts to California, and from Canada to Kenya, Moore is indeed the ultimate “monuments man.” For the past 14 years, his ever-increasing workload has included creating one of the world’s largest bronze groups that, when complete, will extend more than a football field in length.

A self-taught artist and the son of a peripatetic Southern Baptist minister, Moore began modeling clay figures in high school. After marrying his childhood sweetheart and taking a job as a telephone engineer in Northern California, he continued to experiment with the plastic art, learning what he could from books and trial and error before seeking professional direction from Cowboy Artists of America co-founder Joe Beeler. Moore’s cold call to Beeler evoked a warm response and an invitation to visit his Sedona, Arizona, studio. The daylong experience proved “life altering” for the aspiring artist, who continues to revere Beeler’s memory and generous spirit.

Moore was barely 21 in 1978 when he sent his first sculpture, an Indian figure titled Outlier, to a Berkeley, California, foundry for casting. Eager to reduce the time and cost involved in producing such work, Moore and his brother eventually established their own “backyard foundry.” After a few months, however, they decided to relocate to Montana, to learn the trade from experts at the Ace Powell Foundry

In 1985, after enduring four winters in the Northern Rockies, Moore and his wife, Kim, sought a warmer climate in New Mexico. With the experience he had gained in Montana, the artist quickly landed a job at the Shidoni Foundry at Tesuque where he taught himself to enlarge bronze monuments. Seven years and 120 enlargements later, Moore quit the foundry business to become a full-time artist.

By this time he had already acquired 20 commissions, mostly heads, busts and life-size bronze figures. In 1993, a chance conversation between the artist’s father and a childhood friend, Oklahoma oilman Thomas H. McCasland, led Moore to his largest project so far: a tribute to the American cowboy at the Chisholm Trail Heritage Center in Duncan, Oklahoma. Inspired by Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Regiment in Boston, Moore’s ambitious design called for the installation of a massive bronze trail-driving tableau, measuring 11 feet high, 7 feet wide and 34 feet long, with figures rendered in low and high relief as well as in the round.

This five-year project was well underway when University of Oklahoma President David L. Boren asked the artist to create a twice life-size likeness of George Lynn Cross, one of his distinguished predecessors. At the unveiling ceremony for the bronze in April 1996, Boren invited Moore to revive the university’s figurative sculpture program (defunct since 1969) and serve as the school’s artist-in-residence. Moore accepted the appointment and after finishing up his Chisholm Trail monument, moved back to Oklahoma. In addition to teaching, Moore undertook several new commissions destined for the OU campus, most prominently, The Seed Sower, a 12-foot figure of a farmer bearing the face of the university’s first president, David Ross Boyd.

Moore’s reputation for imaginative composition and high-quality execution earned him a steady stream of outside work as well, all of which prepared him for when the Oklahoma Centennial Commission approached the artist in 2000 to create a monument to the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889. His subsequent design called for nothing less than a larger-than-life bronze recreation of the chaos and emotion that attended this colorful and historic stampede for land.

Moore and a small crew that included his sons, Ryan and Todd, went to work even before the multimillion-dollar project was fully funded, and, by October 2005, had installed a wagon and two draft horses on a gentle slope near downtown Oklahoma City. With time and experience the pace quickened, although not fast enough to avoid a four-fold increase in the price of bronze that created a budget shortfall and required the scope of the project to be temporarily scaled back. Nevertheless, 75 percent of the monument was in place by spring 2014, with completion anticipated in 2020.

Paul Moore’s penchant for large-scale sculpture has both literally and figuratively overshadowed his many superb smaller works. The sculptor begins each project, regardless of size, by imagining the finished product. He then begins to look for the unique features that define and illuminate his subject. Moore takes special pleasure in working with live sitters, believing that close observation and personal interaction yield better results than photographs.

A stickler for detail, he also enjoys the historical research that many of his works require. Some of his most imaginative ideas have emanated from Native American mythology and folklore and obscure sources such as the annual reports of the Bureau of American Ethnology.

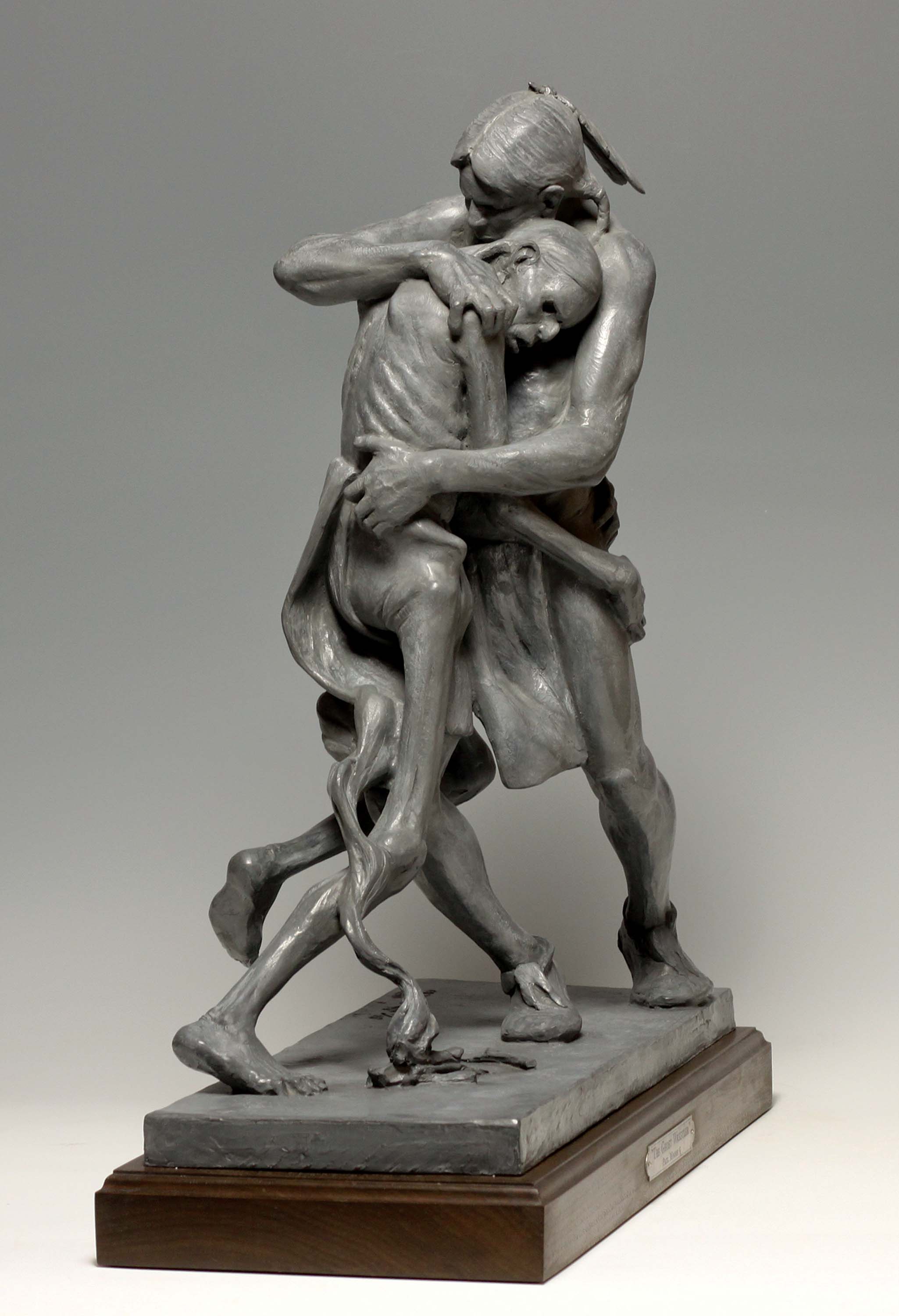

Moore not only possesses a keen eye for human and animal anatomy, but also understands the use of mass and the effects that gravity has on bodies in motion. Such knowledge allows him to take chances and stretch the boundaries of traditional Western American subject matter as he did in his work, The Mourner, which won the Maurice B. Hexter Prize at the National Sculpture Society annual exhibition in 2012. It also contributes to the spirit and action of subjects such as Taos Rabbit Hunt (2009) and The Stickball Game, a silver medal winner at the Cowboy Artists of America Show in 2012.

Recognition and success have not spoiled Moore. The 57-year-old sculptor is still hungry and still excited by the opportunities and challenges that await him in each new undertaking. Over the years, however, his uncompromising work ethic and attention to detail have taken their toll and he has had to endure several back surgeries to repair the damage brought on by years of unceasing and difficult labor. Despite all he has accomplished and the physical toll his toil has taken, Paul Moore still dreams of monuments yet to do. Someday, for example, he wants to produce a larger-than-life memorial to the Native Americans, including his Creek (Muscogee) great-great-grandmother, who walked to Oklahoma on the infamous Trail of Tears in the 1830s.

For Moore, such a work would not only be a fitting counterpoint to his depiction of the 1889 Land Run (an event that involved one of his great-grandfathers), but also a worthy capstone to his monumental career.

- “On the Chisholm Trail Monument to the American Cowboy” | Bronze | 34 x 11 x 7 feet | 1998 | Chisholm Trail Heritage Center, McCasland Park, Duncan, Oklahoma

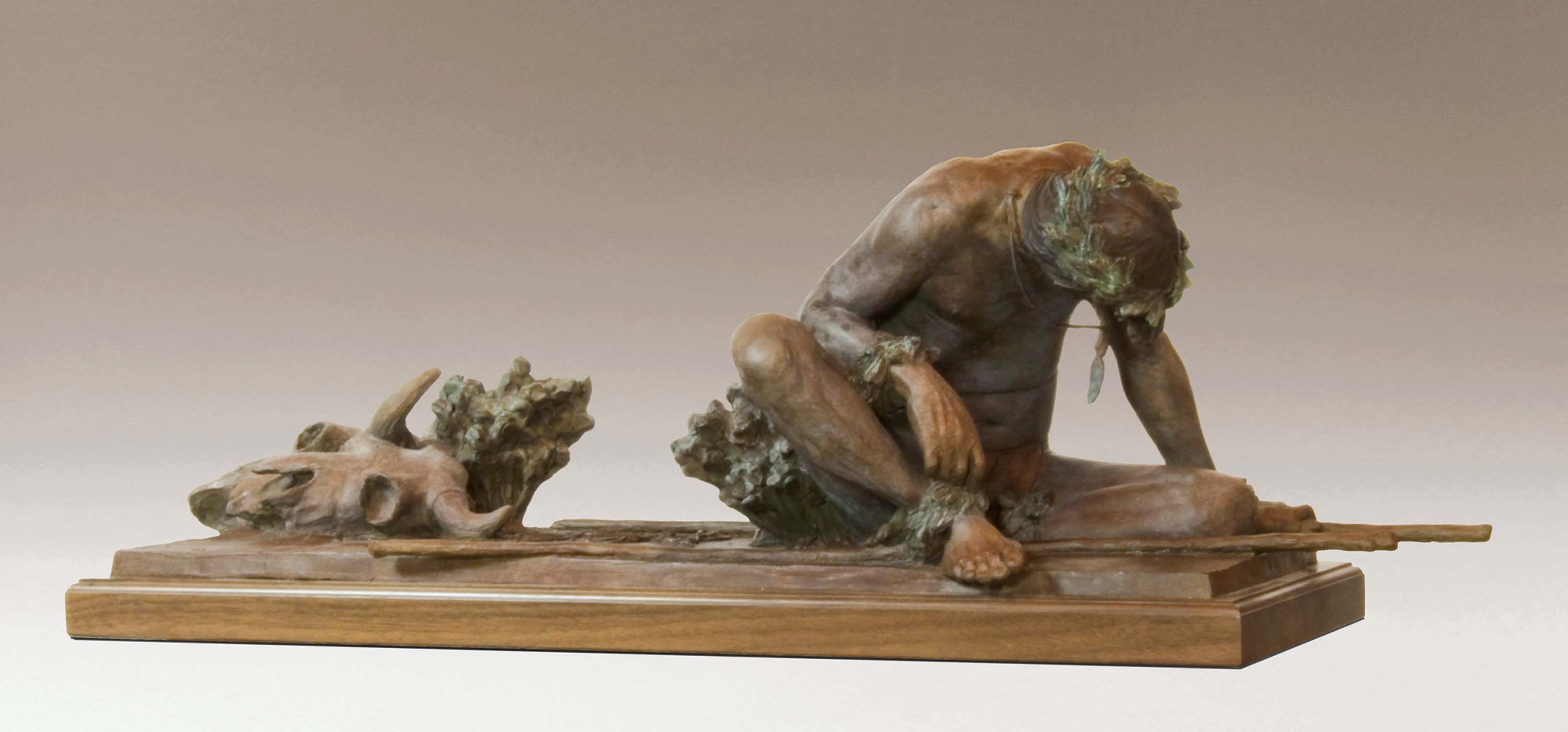

- “Offering to The Sun” | Bronze | 14.5 x 40 x 14.5 inches | 2012 | Edition of 15

- Paul Moore’s larger-than-life evocation of the historic Oklahoma Land Run of 1889 includes 38 people, 34 horses, five wagons, a dog, a rabbit and a cannon. When complete in 2020, the bronze monument will rank as one of the largest in the United States.

- “Hopi Snake Dancer” | Bronze | 42 x 19 x 15 inches | 2011 | Edition of 15

- “The Ghost Wrestler” | Bronze | 19.5 x 10 x 22 inches | 2011 | Edition of 15

- “The Mourner” | Bronze | 28 x 8.5 x 23.5 inches | 2010 | Edition of 25

No Comments