01 Sep Nocturne Man

“You seldom regret what you don’t say when you refrain from adding another brushstroke.”

JOHN FELSING'S SAVORED PART OF THE DAY IS NIGHT, and by every indication he has grown ever more crepuscular and economical in his habits of seeing. When the sun melts away from the rural Midwest, Felsing has a penchant for wandering alone into the forests and glens, whether in 100 percent humidity or 40 below temperatures, adhering to the words of poet Emily Dickinson: “The landscape listens and we hear it call our own name.”

How many artists go seeking their sentient connection to surroundings in pitched deepening blackness when most of their neighbors are asleep?

Even in his pursuit, there is nothing eerily noir or supernaturally foreboding about Felsing’s motivation. Praised for his originality as a maturing American Impressionist, one of his distinguishing métiers is painting modern nocturnes.

For a long time, the moniker of place summoning Felsing has been his native Michigan countryside, evoking universal yearnings for the viewer; though stirring inside of him is a new entreat, this one emanating from the American West.

“His approach to landscape is emotional and intuitive and his improvisational process often leads him to unexpected places,” says Maria Hajic, Felsing’s longtime representative at Gerald Peters Gallery/Santa Fe. “There is a dreamlike quality to John’s work that is difficult to capture in words. Evocative, atmospheric and haunting have all been used to describe his paintings. The unfinished edges of his compositions lead you into another world.”

In autumn 2010, following an extended period in which he was again cloistered away, continuing a transition toward less that is much, much more, Felsing unveiled several new works at Altamira Fine Art in Jackson Hole. That showing, received well by collectors and colleagues, garnered attention and piqued anticipation of what a move West would do to his inimitable perception.

Now, under the den-mothering auspices of Hajic, Felsing is scheduled to be the featured artist at two upcoming events: an exhibition with Carol Anthony at Peters/Santa Fe in summer 2011; and a much-anticipated solo conceptual show, also at Peters, slated for 2012. The theme of the latter: Impressionistic pastorals inspired solely — and soulfully — by Felsing’s sojourns between the hours of dusk and dawn.

“I like the night because I feel completely invisible and unobtrusive,” he says. “I can walk and listen to subtle sounds and widen my perspective and absorb without any distraction. I try to let it all come to me and seep in.”

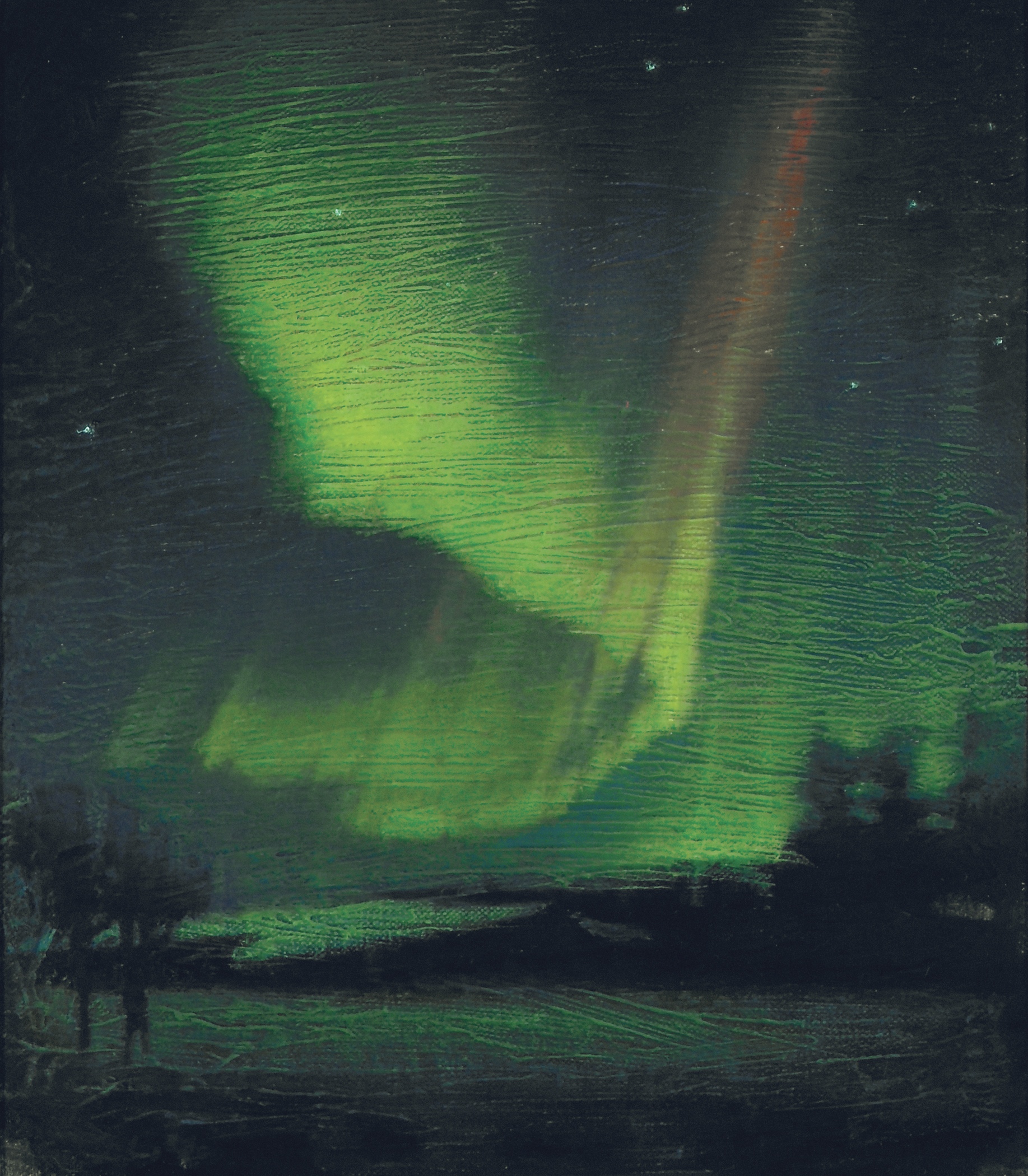

Normally, what guides him into the dim ambiance is illumination by moonbeam and starshine. He is said to have the night vision of a timber wolf. But on a recent humid July evening, he was trailing fireflies that appeared to connect the plane of earth with constellations in the cosmos. During another traverse, as lightning sparked the sky at 4 a.m., the allusive ethereal effect above was akin to standing in the middle of a lava lamp, he says. And during yet a different wee-hour excursion, Felsing gloried beneath a shimmering, colorful display of the Northern Lights, emboldened by a distant sunburst that caused electromagnetic particles to churn in a prismatic river.

Some works hint perhaps at what is yet to come. In Aurora, 17 by 15 inches, the remarkable atmospheric phenomenon is conveyed with paint splotches that appear to be approaching from the back of the linen surface. “This night, the Aurora left images with wings so strong they remained for years, saturated with these epic fragments of memory,” he wrote.

And in the resonant 10-by-12-inch Lilac Moon, tonal abstraction assumes elements of Asian minimalism as the lunar glow (which, after all, is the moon’s surface reflecting sun rays) burnishes highlights upon a tree in the season of full bloom. “Art should take you out of your chair,” Felsing says. “It’s supposed to move you from one place to another.”

Collector Woody Haage says the piece accomplishes that. Haage, whose family founded the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin, owns Lilac Moon, as well as numerous other Felsings. While some fans of artists never want them to change, Haage, undaunted by Felsing’s ongoing shift away from strict realistic representation, believes that he is exuding an inner confidence setting him apart from contemporaries.

Lilac Moon has become a source of tranquil meditation, Haage says. “It’s a scene that I’ve seen a thousand times out my window and whenever I think of that time of day, the twilight, I think of John’s painting,” he says.

The Haage family has Felsings hanging throughout their home, impacting their children as much as any sightline out the picture windows. The pieces range from a portrayal of a moon slung low on the Western horizon, to a night winterscape. Shadows of trees undulate up and over snow mounds and shift in their direction.

“I have skied 150 times at night,” Haage says. “Nothing, no photo I have ever taken, has captured the magic like he did. It’s a painting that when you stand in front, you disappear into it.”

Felsing is, in the eyes of critics, like a voyager verging upon a northern lake frozen over and snow covered. He knows that something glorious lies in the depths before him. Clawing, metaphorically, he digs into the ice to get closer to what he knows is there on the other side, but it remains evasive to the human touch. He acknowledges that he has never broken through, joining every painter who has taken on the impossible journey.

Witness that Felsing does not prefer to paint in burning color flourishes; his textures and muted effusions of mixed oil are the result of hard-fought battles that heighten the effect of his work. He resists the tendency that would engulf many artists attempting nocturnes to set a palette too dark until the vision was lost in oblivion.

While he may drip or throw paint, Jackson Pollock-style, or block in the unctuous keys of color with knuckles or combinations of natural and fabricated instruments, it is what he does afterward to pull himself back — sanding, scraping, buffeting surfaces with thinners and grinding again — creating a disciplined, uncommon window of Dickinsonian translucence.

Feisty by temperament, he eschews labels, regarding them as anathema. If he had to pin himself down, it would not be with an -ism, but through an observation from Oscar Wilde that simplicity is the last refuge of the complex. It includes his role as parent, an occupation that he always put first before painting, further ensuring that his output has remained, much to the consternation of galleries, non-prolific.

With his youngest child, Emily, graduating high school in 2010 and setting out for college, giving the artist his own rite of passage as a newly minted empty nester, she asked her father what it is like to get older.

“I told her that it’s the greatest experience of my life. I wouldn’t go back to any earlier age because I like where my mind is. I loved being her Dad. I try to simplify painting over and over and I get closer to the truth every time I do it. But my old haunts in Michigan don’t speak to me as they once did. I’m wandering again.”

What the viewer discerns in his scenes plays to a paradoxical illusion. Angst is an essential ingredient of Felsing’s persona and in his creative process — grist that friends say the artist courts. His attempt to achieve soothing, mesmerizing surfaces conceals the fitful internal struggle. Deep Meadow, a 9 by 12, is a more traditional Felsing. A portrayal of sanctuary, it is also a statement of personal parting. Nature, he says, has never deceived him. “This meadow is a trusted friend I have visited whenever I needed to hang myself out to dry,” he observed. “This day felt as if I was letting her go … and saying thank you for these rendezvous.”

“Perhaps obsessively so, I find him to be totally dedicated to his work,” says Jane Connell, senior curator of the Muskegon Museum of Art. “In the end, he conveys that delicate balance communicating the sense of a real physical landscape with all of its subtle delicacies, but not much detail, and a strong undeniable emotive quality that can only originate inside himself.”

Felsing’s work was included in a 2008 exhibition of American master Impressionists at the Muskegon Museum. Along with Russell Chatham, he was the only contemporary painter featured among a trove of works by deceased artists that included George Inness, John Twachtman and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Fitting, considering that the first art book he ever owned was a volume on Twachtman given him by his parents for his 14th birthday.

The painter that Felsing has become, however, is not one that squares with the distant memory of artist Pat Magers, a sculptor in Atlanta who works with found natural materials. Magers and Felsing knew each other in adolescence beginning in grade school when Felsing’s mother was her teacher. Often, they would be pitted against one another as the smartest girl versus smartest boy in the class.

On a lark three decades later, Magers Googled Felsing’s name and up came some images showing at galleries. She was astounded. This was not the wildlife painter she expected to encounter. “The works were so evocative. I had no idea when we were young that he had any inclination to go in the direction of where he is today,” she says. Time has drawn him out.

During the 1970s and ’80s, Felsing had fallen into the camp of animal painter. “I was singularly a wildlife artist and I still love the animal world, but my relationship isn’t literal,” he says. The nature artists who served as his polestars were Louis Agassiz Fuertes and Fenwick Lansdowne, Bruno Liljefors and George Miksch Sutton — men known for their bird painting and illustrations.

Felsing would be accepted into Birds in Art at the Woodson Museum. And one painting, On the Edge, portraying gannets on Bonaventure Island, was part of a show that traveled around the world in the mid-1980s. Felsing was labeled one of the bright young talents of his generation. His work sold in galleries and he earned commissions, but with Realism he could not translate the images that were flowing forth from his unconscious. He has struggled through, refusing to pander.

“Everything with John is real in the moment it is happening,” Magers says. “What I respect about him is that he’s brutally honest. He doesn’t compromise. He won’t do something for money and won’t paint the same picture that has won him praise over and over again. He’ll go into the studio with a perfectly fine painting that was developing beautifully and destroy it. What matters is being true to the image.”

Cold wind, angry skies, leafless sullen-looking trees. The post-inferno of autumn colors can leave some in a state of melancholia. Not Felsing, who embraces austerity as the most sublime form of beauty. “You see the true spirit of trees late in the fall. To me there is nothing more spiritual than to watch the blowing leaves in the forest, twirling around trunks of sentinels that rise into the sky and reveal their individual personality, strength and character,” he says.

Felsing holds envy for what those arboreal giants have borne witness to. As Magers notes, many artists rise out of deep-seated insecurities, the product of dysfunctional family lives and less than sanguine periods of psychic development as children. “Compared to many of us, John grew up on the set of Leave It To Beaver, with woodlot playgrounds,” she says.

Felsing will bark back if someone points out his own eccentricities; he is, in fact, well aware of them, though their manifestation is not owed to some traumatic event as a boy. He pays homage to the grounding his parents gave him, encouraging him to wander, delighting in the tales of the wild he brought home. Both of his parents died at home, the artist tending to them; his mother at age 96 and his father at 95. Felsing was with them in their final aura, he says, the moment they each passed. He sat in the room with them afterward, reflecting on the life they had given him. “It’s one of the profoundest things you can ever experience,” he says.

- “Aurora” | Oil on Linen | 17 x 15 inches

- “Fruhlingstimmung” | Oil on Linen | 16 x 14 inches

- “Woodland Edge” | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 26.5 inches

- “Moss Aquarium” | Oil on Linen | 11.5 x 11.5 inches

No Comments