29 Dec Past in Present

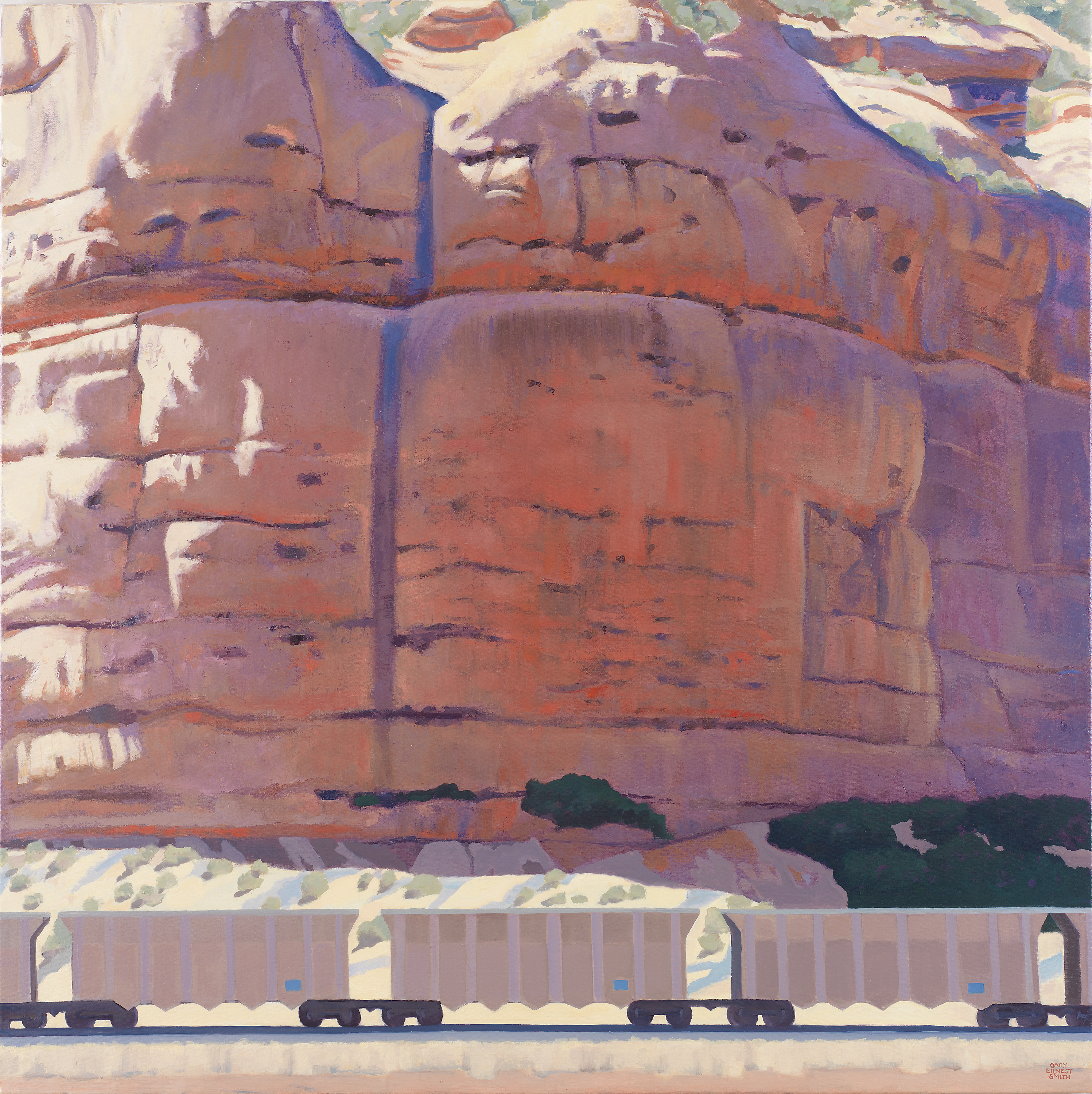

On one canvas, a vast and vibrant canyon meets a rushing train. It’s a painting, so it’s a quiet snapshot. But the colors, the strokes of the palette knife and the composition signal something far more vociferous — a vast, ancient silence meets the loud whistling declaration of modernity.

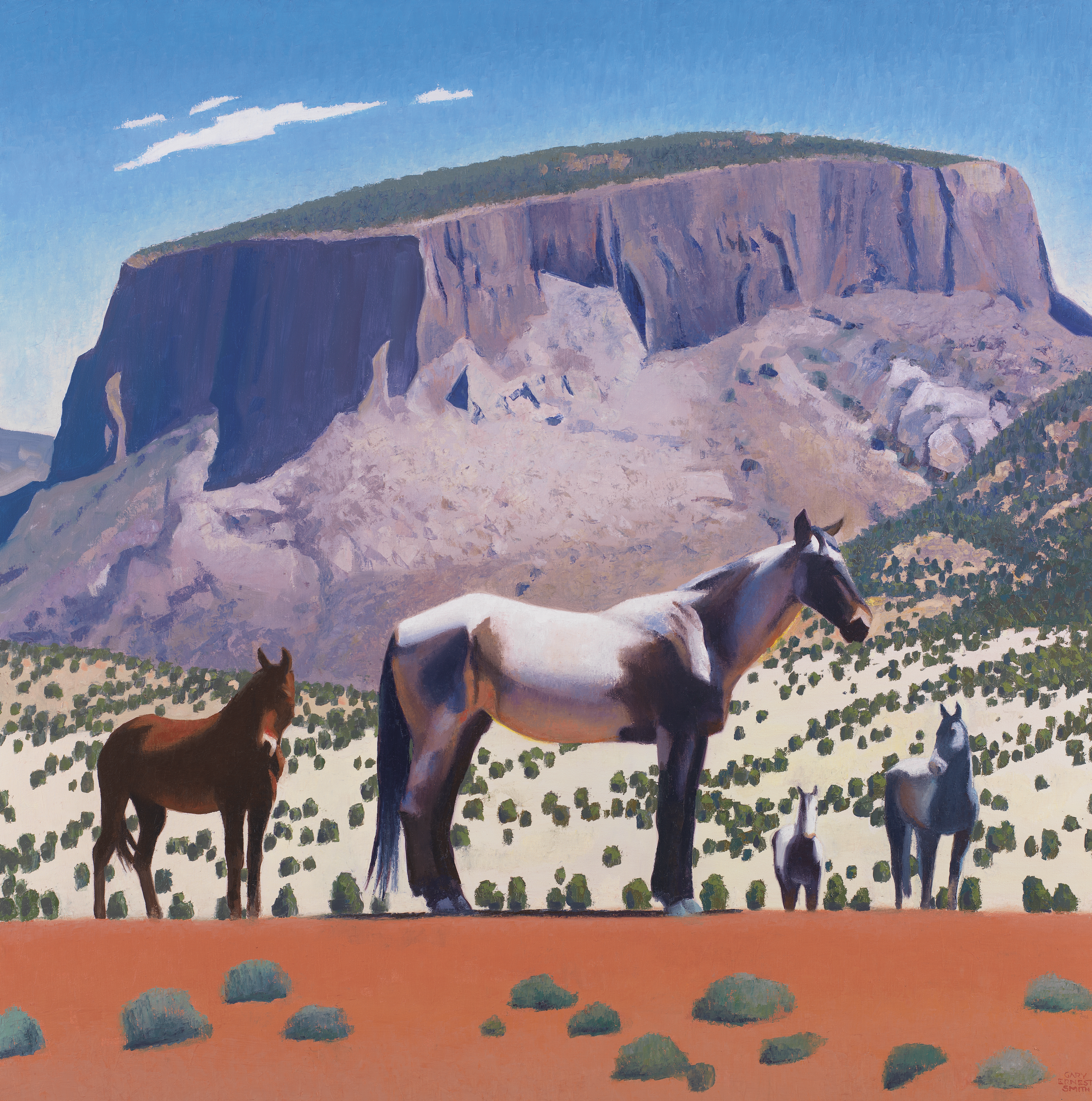

On another huge stretch of canvas, the red — almost Martian — earth of New Mexico meets the gentle pastel of sky. Along the horizon and in the foreground, the graceful shapes of mustangs take in their surroundings from afar.

It could be said that Gary Ernest Smith paints very familiar things. After all, we’ve seen trains. We’ve seen the Western landscapes made famous by Maynard Dixon and John Wayne cinema-scapes. But looking at any one of Smith’s prolific works — Echo Canyon and Mustangs of Mogollon come immediately to mind — Smith presents the West, often on a grand scale, in all its legendary and fleeting glory.

Hailed as the leader of the New West artistic genre, Smith’s career has spanned every acre of Western life — from the habitudinal chores of farm and ranching life that root people to the ground to the evocative landscapes that seem to swallow viewers. All of his pieces feature a unique, color-saturated approach that seems to glow off the canvas a la Rothko. And just beneath the veneer of familiarity is his trademark symbolism that transcends time and place, rendering his works from traditional to modern, from simply beautiful to breathtaking.

To meet the man himself is to step into territory that straddles modern growth and communities, and the wildlife and landscapes that put the West on the map in the first place.

Less than an hour’s drive from Salt Lake City, Utah, the once sleepy town of Highland was awakened by strip malls, sub-developments and clogged traffic ways. Within the melee is a quiet piece of earth, a designated wildlife reserve where birds and trees outnumber convenience marts and construction signs. Somewhere within this unlikely peace, Smith lives and breathes his art.

His home itself is a metaphor for the modern West. A construction crew stirs up little earthquakes, hammering away at the asphalt creating a new street to Smith’s tranquil environs from the rapidly expanding county around him. The dull noise of it can be heard and felt in his studio.

“I resisted it as much as I could,” the artist says of the rumble. Still, despite the drone of the drill, Smith’s space seems cradled in a different dimension with its lighting, high ceilings and rows of paintings displayed on the clean white walls. The works span his career, from farmscapes, fields and immense color-drenched barns to the finite wild lands.

But then again, Smith is no stranger to the rapid changes of the West. Rather, he is a witness. As the son of farmers and ranchers in western Oregon, he grew up with pre-dawn chores on the family’s 60,000-acre property. As much as he respected the life, he knew early on that farming wasn’t his fate.

“I’ve been drawing and painting for as long as I can remember,” Smith says. He sold his first work in junior high. His parents recognized his talent. “My parents were very supportive of my decision to pursue art,” Smith recalls. “Farming and ranching — it’s a hard life. I try not to romanticize it because I grew up knowing how difficult it is and have seen the town I grew up in shrink or disappear.”

In art school and early in his career, he experimented with different styles and media, creating surreal and symbolic works before he drifted back home on the canvas. The figurative nature of his style persisted.

Looking back through his work, Smith’s admirers can identify his unique style. “He’s one of those remarkable artists that retained his identity throughout his evolution,” says Robyn Dill, director of sales at the Overland Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona. “It’s probably been 25 years since I first saw his work and from that first moment, I was intrigued.”

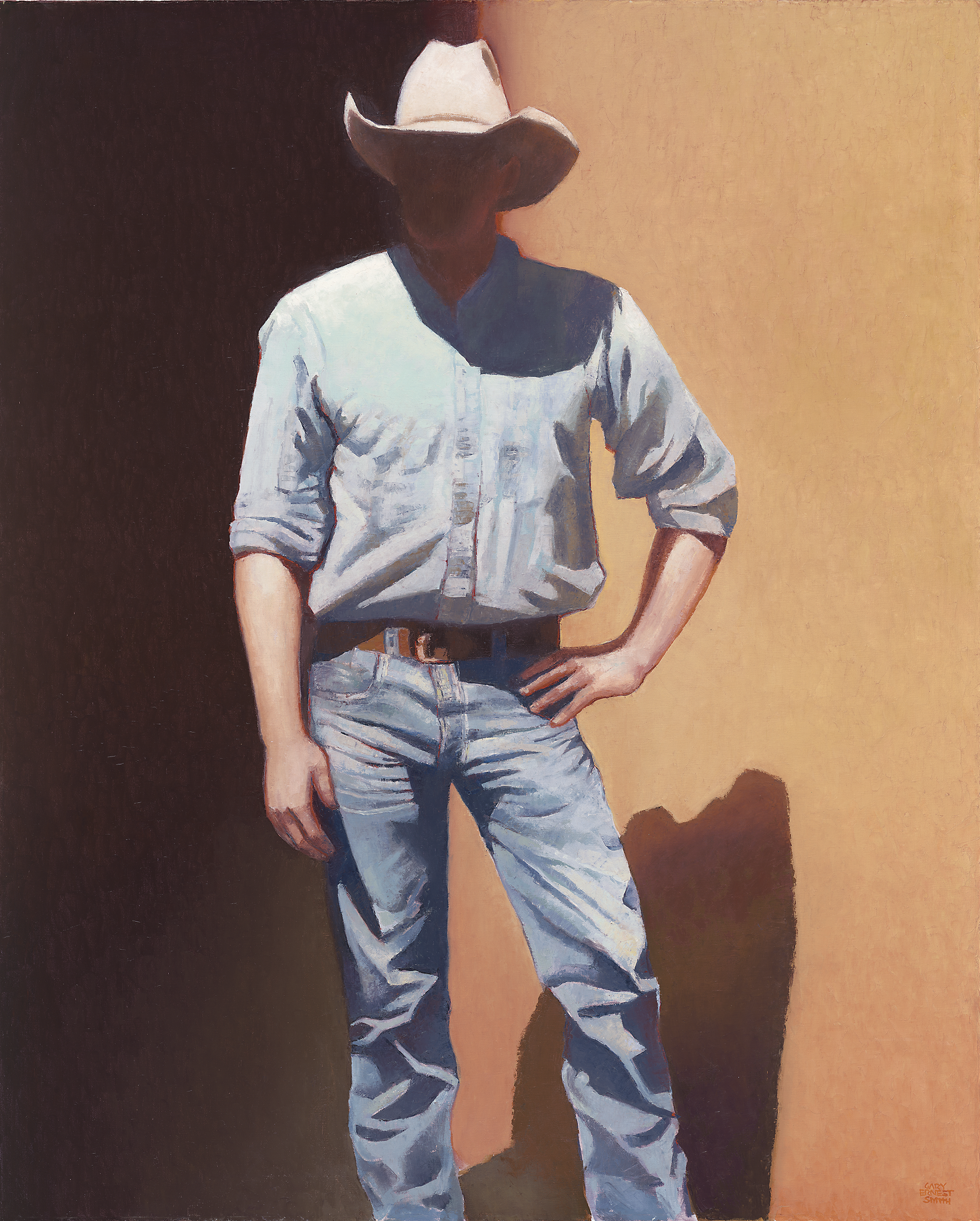

One major characteristic of his work are the faceless figures. In Symbol of America, a strong cowboy figure poses dominantly, almost defiantly. His face is shadowed by the wide brim of his hat, but it’s obvious that the figure is staring right at the viewer. Arms crossed and wide-shouldered, he stands alone, self-assured. Whoever he is, the man is an icon.

Smith can sketch, paint, illustrate and sculpt as proficiently as any talented artist. He purposefully leaves the details of the face vague to express the idea more than a literal person. It’s more than anonymity. To hear Smith tell it, each supposedly faceless face has a story. The young boy in Memories of Home is Smith himself, a self-portrait as a child. In Dry Farm, he captured a neighbor in Highland, long before the suburban sprawl, standing on his land.

“He has a real feeling for the subject,” Dill says. “He can relate to his painting; there’s an actual love of subject matter.”

For Smith, his upbringing cultivated the respect for the West. But for his buyers, reasons vary considerably. Trudy Hays is the director of the Overland Gallery and sees firsthand clients falling in love with Smith’s style and representation of the area. “We have collectors from California to England,” Hays says. “In New York City, a client recently hung a huge piece in their loft. The piece worked in a contemporary setting.”

No matter their progeny or where they call home, people seem to relate to Smith’s work. “The [paintings] just absolutely come alive when you take them out of a gallery setting and put them into a home,” Hays offers. “Even people who might not buy a piece admire his work. There’s serenity to it that draws people in.”

Though as livable as Smith’s pieces are with bucolic landscapes and portraits of Americana, Smith’s impact on American art is more transcendent than the private sphere. Smith’s pieces can be seen in numerous museums from Springville, Utah, to Phoenix, Arizona, to Denver, Colorado.

“There are some pieces you just see for the first time and you know they belong in a museum,” Dill says.

One such piece is Mustangs of Mogollon. “It’s a wonderful composition,” Hays says. “Smith has a tendency to push the color, which is spectacular in this piece — burnt sienna, salmon and other vibrant orange hues that push the landscape.”

Still, New West as an artistic genre is a largely unfamiliar term. For many, Western art is Ansel Adams and Maynard Dixon. Today, many contemporary artists evoke a romantic, almost fantastic representation of cowboys and Indians and life on the range.

Smith sees his role differently as an artist. “There are painters who evoke scenes of the Old West,” he says. “Then, there are painters who were of the Old West. All they were doing was chronicling what was around them.”

He points to several works in his studio, drafts of larger works. Among them is a tiny rendition of Mustangs. “I suppose I’m trying to capture these spaces before they are gone,” Smith says thoughtfully, the construction drill still humming in the background. “I’m a New West artist because I have been around during this transition from Old to New.”

His faceless figures and bold barns silently watch over him in his studio. Whatever might be built beyond his studio walls, a serene, vibrant patchwork of the past in present thrives. Among these canvases is the next American Gothic.

- “Long Shadow” | Oil on Linen | 48 x 72 inches

- “Echo Canyon” | Oil on Linen | 48 x 48 inches

- “Man of the West” | Oil on Linen | 60 x 48 inches

- “Family Tree” | Oil on Linen | 60 x 60 inches

- “Symbol of America” | Oil on Linen | 40 x 30 inches

No Comments