04 Aug Plain Hard Work

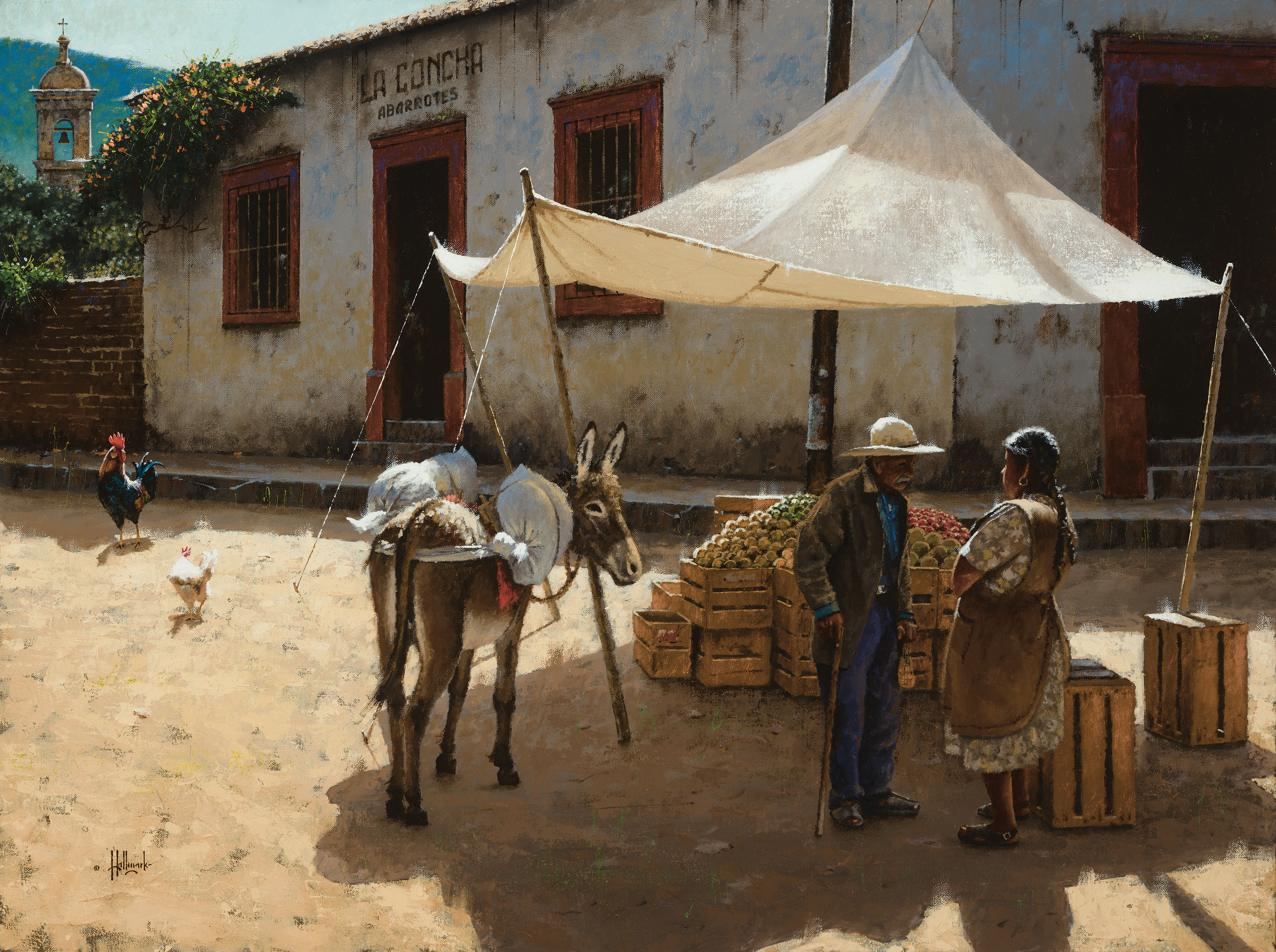

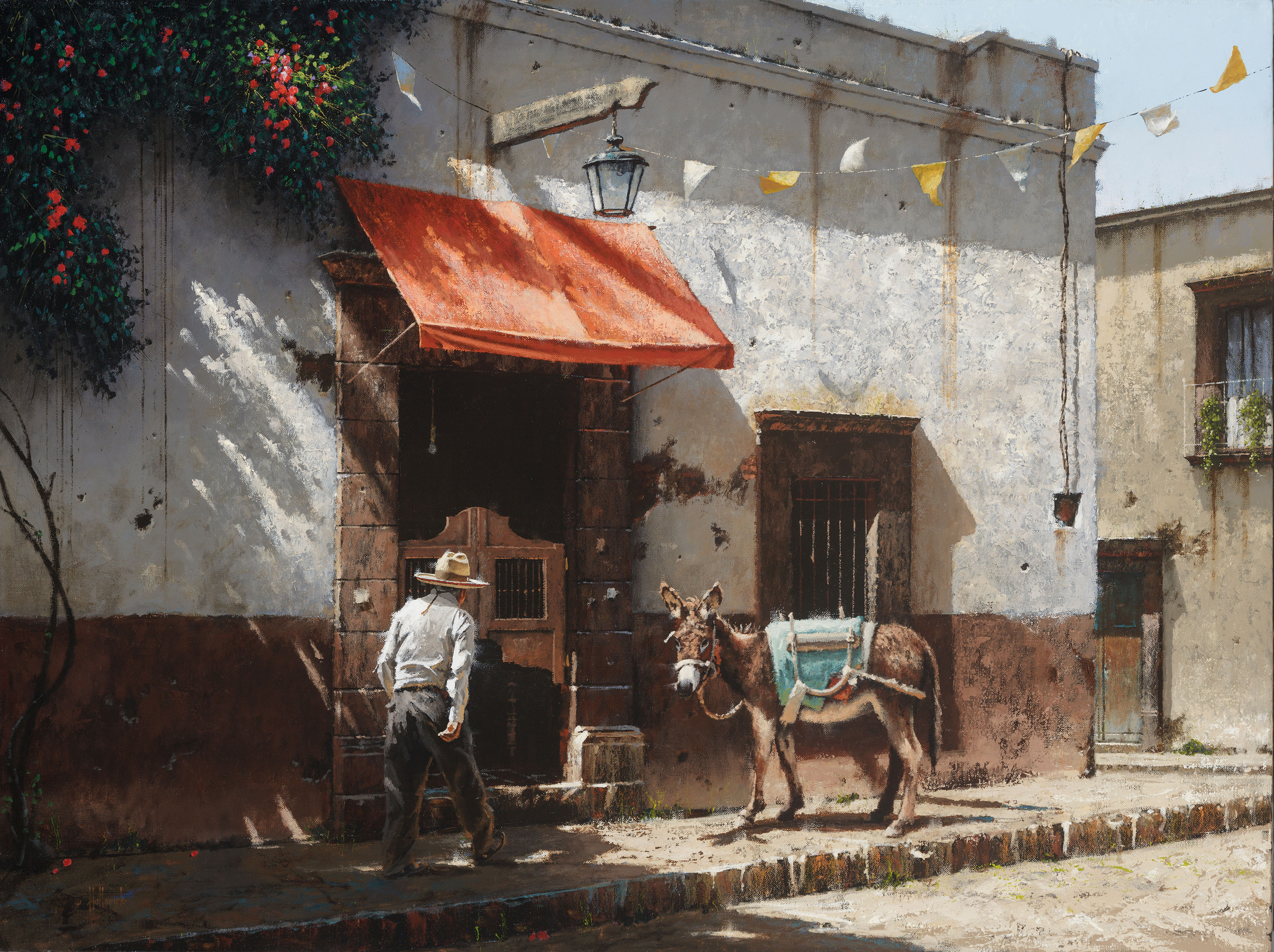

ALTHOUGH THE TEXTURES AND COLORS THAT MAKE UP a George Hallmark composition are created in his Meridian, Texas, studio — with Utrecht oil paint applied to linen using both his palette knife and nylon brushes — they reflect a world beyond his four walls, places he has seen in Mexico, the American Southwest and across Europe. His painted scenes intrigue the eye even more than the actual sites as you and I might view them. They are an exploration of constantly changing atmosphere, sunlight and shadow. They are a reflection of places aged in time, bleached by the sun, given character by reflections and shadows, colored by trees, shrubs and vines. They are perfect expressions of architecture at home in the landscape.

Hallmark is a Westerner. To be more precise, he is a Texan by birth and grew up in a family deeply influenced by his father’s music. Elgin “Curly” Hallmark was a drummer who played with Bob Crosby and the Bob Cats and many Fort Worth and Dallas area bands. George learned to play from his father and still plays on occasion.

Young George was also influenced early on by several teachers who encouraged him to draw. He attended a junior college in Fort Worth and took art classes at Texas Christian University. An emphasis on Abstract work discouraged him and he left school to hire on with a construction company for several years. Eventually, Hallmark applied for a job within the firm to draw architectural delineations, perspective drawings created from design blueprints. Poring over books one weekend, he created demonstration drawings, was given the job and worked in the field for a number of years before going out on his own to do freelance delineations and designs. It was an experience that taught the artist much about architecture and structure.

By the early 1970s, Hallmark was creating mixed-media paintings and opened a gallery with a partner. Friends introduced him to the late Bill Burford at the Texas Art Gallery in Dallas. One of Hallmark’s character studies of a farmer was consigned to the gallery and quickly sold. Not long after, George Hallmark dedicated himself full-time to art.

He was well acquainted with painters who focused on the West’s cowboys and Native Americans, but Hallmark wanted something else. “I was trying to find a niche in the art world where it seemed like everybody was doing cowboy things. I needed to find my own way,” he says.

His ever-increasing circle of artist friends and acquaintances had an impact on Hallmark’s work. He met established Western artists James Boren, Melvin Warren, James Reynolds and Olaf Wieghorst, all of whom were willing to critique his work. Encouragement also came from Lowell Smith, a Rio Vista banker who commissioned a series of nearly 30 historical paintings of that region. Many of these early works reflected the precision of Hallmark’s architectural drawings, but he was starting to paint in layers, blocking in with dark colors and building upon them with lighter layers.

It was in the late 1970s that Hallmark made the acquaintance of Bill Whitaker, who was teaching at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. From Whitaker, the artist learned about technique, but the real lesson, Hallmark says now, was about how skill grew from repetition, perseverance and dedication.

In the early 1980s, Hallmark moved to Bosque County, Texas, and joined his friend, Martin Grelle, as a student in the first class taught by Melvin Warren and Harvey Johnson at the Cowboy Artists of America museum in Kerrville. Bob Pummill befriended Hallmark as well, and Clifton artists Tony Eubanks and Bruce Greene became close friends.

Although Hallmark’s work was maturing, he felt that something was lacking. He had been working on landscapes, but focused more and more on depictions of architecture. He had become aware of the work of Clark Hulings, having attended the senior artist’s one-man show at the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City in 1976. The work left an indelible imprint on Hallmark.

“Here I came from a tight line background, but I really enjoyed the looseness of Hulings’ work.” He was also attracted to Hulings’ use of light and its relationship to shadow. Hallmark later visited Hulings’ home and studio, talked at length with the artist, and admits to imitating his style for a time. Hallmark was flattered when his work was compared with that of Hulings, but there was a more important lesson to learn from the older artist. Even into his 80s, Clark Hulings took classes and constantly worked at developing his art. He encouraged Hallmark to also keep learning. The younger artist did just that and, over time, his style grew to become distinctively his own.

“You have to go to your own studio and apply your own paint in your own way. I learn all the time. Art is a total learning process,” Hallmark says.

Through the 1980s, Hallmark’s work became increasingly recognizable to patrons and other artists. He first began selling his work through Trailside Gallery. By the 1990s, he was exhibiting at the Autry’s Masters of the American West and at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum’s Prix de West. Today his works are in the collections at the Autry, the Eiteljorg Museum, the Booth Museum and in important private collections that include those of other artists who hold him in high regard.

Hallmark’s stature in the field was confirmed in 2010 when he was selected for a one-person show at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art. He had been a part of the artist roster at the Eiteljorg’s Quest for the West art show and sale from its founding in 2006. Selection as the show’s Artist of Distinction in 2010 placed him in the company of an elite group of artists honored before and since.

Despite the accolades and awards, Hallmark is still committed to learning. “I keep finding things I haven’t tried or painted. I am always seeing something different that has a different light effect or a new challenge. I’m always pushing myself and trying to see something different. I haven’t done my best painting yet. I’m always striving to do better,” he says.

George Hallmark works six days a week, focusing on one painting at a time. His talented wife, Lisa, supports him in every way and is his most constructive critic. When you stand before a finished painting by George Hallmark, you are experiencing a unique visual story. The artist’s dedication to his craft can be both seen and felt.

“I try to make every painting as good as I possibly can. I want to look back on the body of my work and see a good variety of the best I can create,” he says. Along the way, George Hallmark has created a unique and important addition to the art of the West.

- “Everlasting” | Oil on Linen | 24 x 36 inches | 2015

- “Mi Amigo Espera” | Oil on Linen | 36 x 48 inches | 2015

- “Sombras de Espana” | Oil on Linen | 48 x 36 inches | 2015

- “El Corazon” | Oil on Linen | 48 x 48 inches | 2015

- “Bienvenido” | Oil on Linen | 36 x 36 inches | 2015

No Comments