11 Jul Rancho Sabino Grande

Behind the bar at Rancho Sabino Grande is a mural. At first glance, it resembles a Works Progress Administration piece from the 1930s, its smooth, flattened representational images and themes echoing a regional history in a specific landscape. It’s a great conversation piece, says interior designer William Peace, whose Atlanta, Georgia, and Bozeman, Montana-based firm, Peace Design, commissioned the work from Gorman Studios of Vancouver. Closer inspection reveals vignettes — both old and new — that tell a story of the owner, Rod Lewis, a self-made man born and raised on a ranch in South Texas and the first American wildcatter to drill for oil in Mexico in more than 30 years.

Sliding doors open to a covered porch and views of the lake and landscape beyond.

Not surprisingly, there’s a whole lot of Texas in the mural. Longhorns and cowboys figure strongly in the foreground, while airplanes — specifically World War II fighter planes — fly over a line of oil derricks. Out of a background of snow-covered, high mountain peaks flows a river. It could be anywhere; Lewis has traveled the world. The front of the bar features an antique book-matched Jasper stone border inspired by notable Italian villas, including the Villa Borghese. It’s just one of many treasures found throughout the home of a man whose life’s work is rooted in the earth’s strata.

The gable entry, with sculpted classical details in stucco, was inspired by Cape Dutch and Spanish architecture. The door incorporates a traditional ox blood antique finish.

Located west of San Antonio, the 24,000-square-foot home sits on a bluff overlooking a twisting line of ancient cypress trees — called sabino in Spanish — that frame the Sabinal River and the open and rolling Texas Hill Country plains. It’s such a special property, explains San Antonio architect Michael Imber, “that the State of Texas tried to acquire it as a state park.” A clear river runs year-round, attracting a variety of wildlife and birds. Over the years, the river channel was redirected, leaving a riparian plain. Within these boundaries, Lewis built a lake to attract the exotic game animals that roam the 4,500-acre property, including buffalo, gemsbuck, red deer, zebra, and a giraffe family.

The lounge features an antique book-matched jasper bar front and commissioned mural depicting the life and adventures of homeowner Rod Lewis.

The challenge Lewis presented to the design team — which included Peace, Imber, and landscape architect Jim Hyatt of Denver-based James Hyatt Studio — was no small feat, but typical for the sort of guy who has worked hard and has a constant curiosity for energy, motion, and living big: Build a home that will last forever. “It’s meant to be a legacy property,” says Peace, “not only for his family that he knows right now but for a future he can’t even realize.”

Limestone fireplaces and exposed beams give scale and structure to the stately great hall. The textural richness of the furnishings adds comfort, and the artwork reflects the homeowner’s interests.

What does it mean to build a house that will last forever? For some, it means designing a structure engineered to withstand earthquakes and major weather events. Others use their homes to interpret history, almost like a living museum. Still others — like Lewis — want a home that references the past but grows over time to honor and anticipate current and future uses.

A vanishing-edge pool overlooks the lake and exotic game reserve located on the property.

“We wanted the house to read as a palimpsest of epochs, a sort of a layering of history,” says Imber as he describes the historical references and functionality, including the timber framed stone structures built by German immigrants in the mid-1800s, embedded in the architectural concept. “There are historic structures in this part of Texas that range from northern European settlements to white-washed forts. In many ways, Rancho Sabino Grande is very similar to the Alamo, where the bottom half is Spanish and the top pyramid is German. The base incorporates elements from historic Spanish buildings, and then we designed a Dutch gable, complete with curved, ornamental volutes on the top […].”

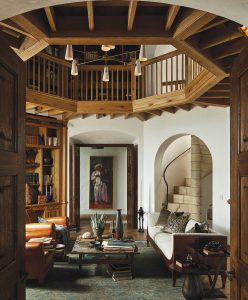

The vaulted two-story library is wrapped in warm-toned walls made of 1,000-year-old sinker cypress. A portrait by American painter Wayman Adams creates a focal point.

While the architecture is meant to reflect generations of Texas ranch life, the interior design reveals much about the owner’s interests and passions. There is a lot to look at, but the genesis of the ideas was never about simply filling space. Instead, explains Peace, who spent five years working with Lewis on the project, the home is a compendium of curiosity, where every item was selected for the story it tells. And from the beginning, the focus centered on how to relate the interiors to Lewis’ “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” lifestyle.

A curvilinear tusk from the owner’s private collection adds contrast to Son of Grace, a 93-by-77-inch oil painting by Canadian artist Kathleen Morris.

On any given day, a head of state is as likely to walk through the front door as is a neighbor from the next ranch over. As such, the program for the home had to accommodate daily living as well as large, stately gatherings, which meant that materials, furnishings, fabrics, rugs, wall surfaces, and spatial layout had to stand on their own to coexist with the legacy projected by the architecture and surrounding landscape.

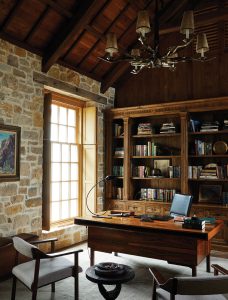

In the office, a Swedish rosewood writing table is flanked by two Jean Gillon chairs.

The interior character of the home embodies a palette that is simultaneously sophisticated and casual, explains Imber, a characteristic of Peace’s design ability that was particularly appealing to Lewis. A highly curated amalgam of stand-alone antique and contemporary fine art and furnishings complement the home’s highly crafted oak, walnut, cypress, and stone finishes, all chosen because they reflect the richness of the surrounding landscape.

The homeowner’s bedroom looks out over the expansive Texas Hill Country.

Part listener and interpreter and part curator of curiosity, Peace embraced the promise of possibility within the project, with the caveat that the richness and texture of the interiors must have the stability to stand up to the architecture, its relationship to the landscape, and Lewis’ studied interest in both provenance and potential. Early in the project, the team traveled to Italy and introduced Lewis to a geo-archaeologist who specialized in marble. A deep dive into the origin and unique structure of Rome’s most precious marbles led to the acquisition of extant marble for use throughout the home.

In the dining room, two multimedia pieces by Atlanta artist Todd Murphy flank the custom-made solid claro walnut dining table. In the alcove, a crystal geode from the owner’s collection is displayed on an antique cabinet.

“Lewis trusted our instincts,” says Peace. “The opportunities were wide open for what we thought was appropriate given his interest and his passions.” In the living room, for example, a 7-foot fossilized sauropod leg is displayed side-by-side with a modernist sculpture and a 1950s cocktail table inset with a piece of petrified wood. Binoculars, sourced from a dealer in New York City who specializes in World War II Japanese Naval instruments, sit on a custom stand in front of the windows where Lewis can observe the animals as they come in for water. “That’s about as specific as you can get for a collector,” says Peace, laughing.

The owner’s collection is displayed in an antique cabinet in an alcove highlighted by traditional leaded windows. Elsewhere in the home, Peace used paneling hewn from solid gunstock walnut and trimmed by the unique Italian marble baseboard, an application he says is unusual because it’s typically reserved for making fine gunstocks. And, in Lewis’ library, Peace presented three types of finishes: sheetrock, basic wood paneling, or millwork made from ancient cypress logs found in a Louisiana swamp. “Guess which one he chose?” the interior designer asks with a laugh.

A painting by Texas artist Julian Onderdonk hangs over a George Nakashima cabinet, the last piece he designed. It was completed by his daughter, Mira, after his death in 1990.

Peace was able to source pieces that were used appropriately — but, more importantly, held a strong story — by working with a network of art and antique dealers around the world. “We are curating a living collection for him. It’s really the beginning of something that, over time, can become incredibly special.”

“I hope that when someone walks in here in 20 years,” adds Peace, “they see the wear and use, and that someone has really lived there. It’s got soul.”

No Comments