24 Jul Roxanne Swentzell

ROXANNE SWENTZELL, A SANTA CLARA PUEBLO SCULPTOR, lives at the confluence of two cultures treading gently but surefooted in both worlds. Wide, clear eyes look to the future while she stays grounded in the past with respect for the earth, family and tradition — celebrating feast days, ceremonies and dances and perpetuating traditions. Her art goes backward to the traditions of her ancient Pueblo culture and forward in time, simultaneously molding together the shared human experience and emotion that transcends and binds all people for all time. Her sculptures, commissioned for the lobbies and grounds of public spaces, are permanent installations at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, the Santa Fe Convention Center, the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Cartier in Paris and Museum of Wellington in New Zealand, as well as having been showcased at the White House in Washington, D.C., and museums and galleries worldwide.

As a child, Roxanne had a speech impediment and was unable to articulate her feelings. An intense need to communicate prompted her to gather scraps of clay from her mother, a potter, to form figures that showed how she felt. In the first or second grade she molded a small desk with a dejected little girl slumped in it; hair falling forward to hide her tears. This to show her mother that she hated school. Sculpting was her voice, her emotional outlet, her refuge — it was not, for her, art.

Roxanne was born in 1962 to Ralph and Rina Swentzell in Taos, New Mexico. Her father was a philosophy professor of German descent; her mother, a Santa Clara Pueblo woman from a family of artists and strong individuals — the Naranjo family. Her mother’s art was of the earth, her father’s appreciation of art was that of the great masters of the world. Roxanne, now extremely articulate, says she had these different perspectives clashing in her.

Swentzell attended the Institute for American Indian Arts in Santa Fe before graduating from high school. At 17 she left home for the Portland Museum Art School where she found an uncomfortable disconnect between art and life. After a year, she moved back to New Mexico. At 20 or 21 she returned to Santa Clara Pueblo, lived in an army tent with her two babies, and built an adobe brick house. Her incredibly creative life took off on her native soil — the land that carries her stories and history.

Twelve miles north of Santa Fe we arrive at Roxanne Swentzell’s adobe Tower Studio at the Poeh Center on Pojoaque tribal land. Her friend, George Rivera, with whom she went to school, serves as Governor of the Pojoaque Pueblo and built this art complex off Highway 84/285. The tower sat vacant for 10 years, occupied only by pigeons until Roxanne gathered her family to help her turn the space into a glowing gallery with vegas and latillas, pine floors and plastered walls. We wander the property admiring her sensuous sculptures, which visually edit the purity of emotion — pain, disappointment, healing, mother love, romantic love, humor — in a sense, a diary of her own emotional life. The hands, feet and head are oversized and more detailed, as they’re naturally more expressive.

Roxanne arrives looking like a picture: beautiful and serene in a flowing skirt and shawl, carrying a lovely basket instead of a bag. She has an energetic enthusiasm with a calm demeanor, and a seriousness balanced with a childlike playfulness. Upstairs in her tower studio, as her hands move over the clay, confident and strong, she says, “I am captured by people who are careful with what they do, whether it’s a mechanic, carpenter, gardener or bread maker.” It has been her quest to do what she does with care — making sculptures, raising children, gardening, baking, dancing …

It is clear in her work and in her essence that the artist embraces the native philosophy of balance between opposites — day and night, summer and winter, male and female, earth and sky. If opposite powers are balanced, none can dominate the other. Her life is an alliance of nature, art and family.

Roxanne has an intense relationship with nature and has established a sensitive balance with Mother Earth. As a child she helped her mother dig clay and mix it. She now buys her clay. “But,” she says smiling, “it’s still of the earth.” She has created a productive oasis of flowering trees and gardens in that high-desert landscape — a haven for her native turkey flock, bees and two sheep. Undaunted by physical work, she can be found using a chainsaw, driving a backhoe, picking tomatoes and canning tomato sauce, weeding or watering the gardens, feeding and talking to her animals, baking bread in the outdoor Pueblo pante oven that she built or collecting native seeds from her gardens. It would not be unusual to find her grinding corn that she grew from native seeds, on a bicycle-type mill. For Roxanne, the relationship between art, work and the earth are at once inextricably linked and all consuming.

In an effort to promote sustainable agricultural practices and preserve the native culture, Roxanne founded the Flowering Tree Institute, a research and education organization that relates to “permaculture … a way of looking at the world based on the laws of nature.” She has collected native seeds that were quickly being lost: Anasazi corn, Hopi corn, Taos blue corn, Pueblo melons, tomatoes, peppers, greens and squashes and Hopi lima beans — “The best I’ve ever had,” she says with passion. The seeds are propagated, harvested, carefully labeled and stored in a cabinet, which, she says, is “the gold of the place.”

Roxanne has balanced family and art and both have thrived as a result. Her daughter, Rose Simpson, at 25 has already established herself as a prominent artist. Their work showed together at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, in an installation entitled Mothers & Daughters, Stories in Clay, featuring the art of three generations of Naranjo women (three mothers and four daughters) from Santa Clara Pueblo. Roxanne said of her grandmother, Rose Naranjo, the family matriarch of these well-established artists, “… for five generations this woman created a world that spun around her, extending far and wide, pulling our many nuclear families into her orbit. … But the times had changed, and the Western mind-set of individualism had seeped into the Pueblos and we, too, wanted our own lives. … The Pueblo sense of one large, extended family of cousins, aunts and uncles, grandparents and great-grandparents had been pierced by the sword of ‘Me versus You.’ ”

Community was the theme of the commissioned piece that Roxanne recently completed for the Santa Fe Convention Center. In the Pueblo sense, as her grandmother demonstrated, the community is the “flowering of generations.” In this sculpture, the baby is the center surrounded by the loving arms and hands of parents, siblings, grandparents, great grandparents, aunts and uncles.

Sabrina Pratt, Executive Director of the Santa Fe Arts Commission, said, “Roxanne responded to our call for work by Santa Fe area artists with an idea that resonates with the building. Her concept of community, executed in her signature artistic style, was an opportunity we could not pass up.”

Swentzell was chosen to do the auditorium wall sculpture for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). It was to represent indigenous peoples of the Americas. She didn’t know all tribes so broke it down to the very core of having a center and balance, which she believes is the foundation of all indigenous people. She sculpted males and females holding hands, which made a center space from which they spin out. She says, “It’s bigger than indigenous people — it’s everyone, so I call it E-wah-Nee-nee — for ‘life in all directions for all of us.’ ”

Dr. Bruce Bernstein, who served as director of collections and research for the NMAI for 10 years and is now the executive director of the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (known for organizing the Santa Fe Indian Market), said, “Roxanne’s artistic vision provided an opportunity to honor the legacy and heritage of Native people and to make a statement about contemporary life. So much of her work is about balancing the many worlds she walks in — from the deeply traditional to the ultra modern. Somehow, some way, she manages to mold into a single piece the ancient origins of life and modern challenges of raising kids and making a living.”

Of Roxanne’s NMAI wall sculpture, he says, “The sculpture is so luxuriously soft and feminine; I marvel that she transforms metal into such softness. The piece has a wonderful narrative and thus introduces and serves as the entrance to the auditorium, the space in the museum for Native people to tell their stories.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne penned, “Highest truths through the humblest medium.” From clay, Roxanne Swentzell’s art touches the truth of emotion, recording the language of the soul and the historic complexity of ancient cultures with lessons for a modern world. Beyond the story of culture she sculpts the truth of humanity. Having come to terms with the clashing cultures in her own life, Roxanne knows, “The world can come together. It’s not easy, but it’s possible.”

- Roxanne and her mother Rina Swentzell

- Swentzell’s Tower Gallery at the Pojoaque Visitor Center north of Santa Fe.

- Sorceress, Coiled Earthenware, 11 x 36 x 4 inches, “a magical being sensing all that is around her.” Collection of Margaret Sink

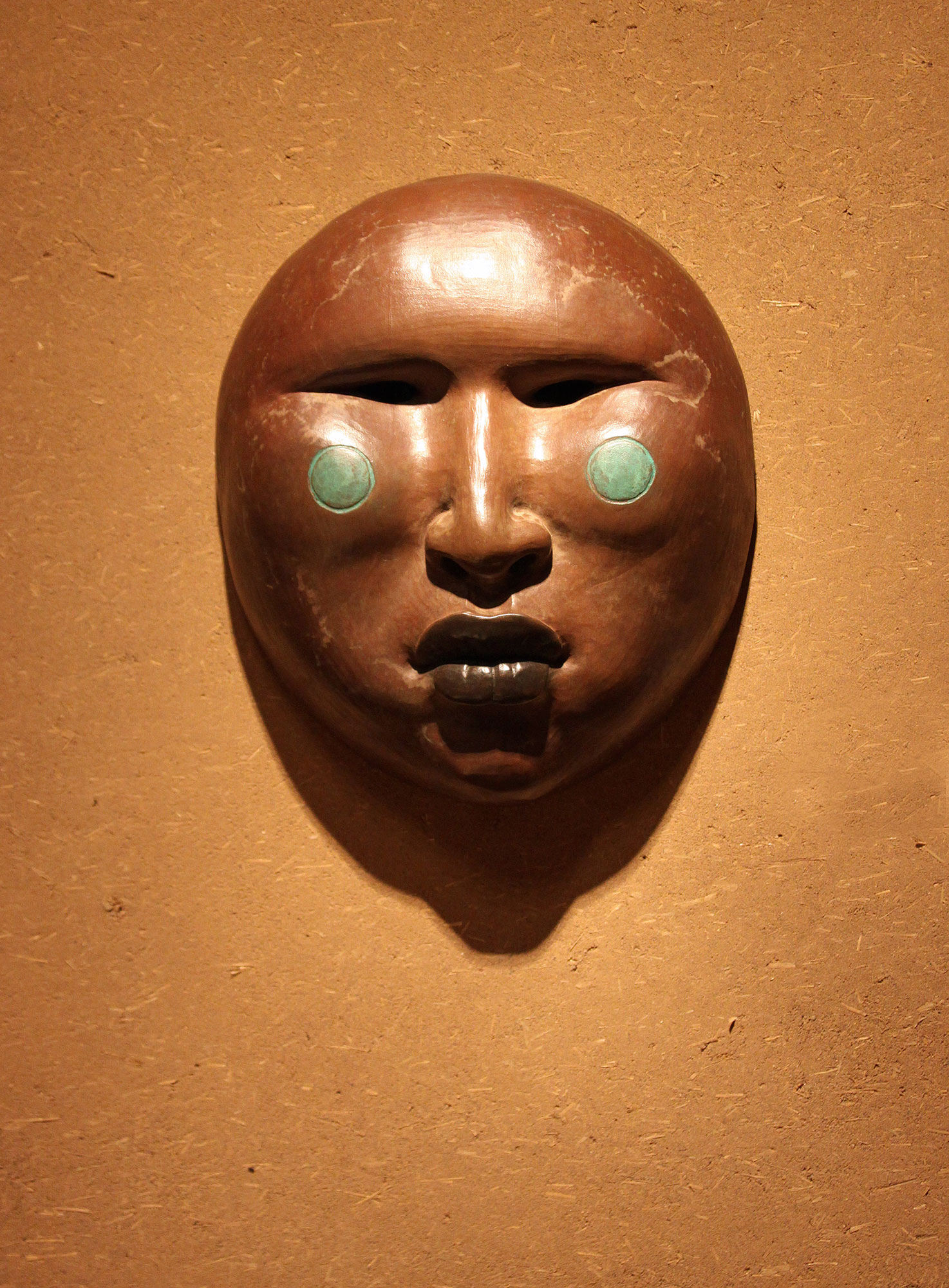

- Smithsonian Mask, Bronze, 12 x 14 x 2 inches, one of eight masks commissioned for the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C

- She Was Me, (detail) Bronze, 10 x 16 x 12 inches — “She looks at a picture of herself as a child. What does she feel? So many thoughts and emotions. With this figure I pray for eyes to look upon ourselves without judgment and an open heart. What would we see then?”

- Woman in Stone, Bronze, 10 x 6 x 8 inches — Originally carved out of stone, “she holds the quality of still being contained within herself, within the stone she emerged from.”

No Comments