01 Aug Santa Fe's Hidden Gem

BEHIND AN UNASSUMING ADOBE WALL ON A TRANQUIL RESIDENTIAL STREET IN SANTA FE, the School for Advanced Research is quietly celebrating its centennial anniversary. In a community that is synonymous with art and culture, SAR, or simply “The School,” is Santa Fe’s hidden crown jewel. Started in 1907 as the School of American Archaeology, the organization has transformed over the century with steady and prolific contributions to the worlds of Native American art, culture, history and global anthropology.

Catering to a passionate audience eager to learn about the human experience through indigenous art, anthropology, history or sociology, SAR sponsors numerous opportunities for continuing education through public colloquia, lectures and field trips. The School houses an extensive library of resource literature and has a press devoted to publishing educational books, research papers and collaborations as well as in-depth art history. “We’re all about education,” explains President and CEO Dr. James Brooks. “Although we’re a fraction the size of a Harvard or Yale, we represent the best of the best in educational and research standards. The collection is without peer — no collection is as rich or well-documented.”

The collection Brooks refers to is a renowned and significant assemblage of Native American pottery, basketry, jewelry, weaving and painting, all stored in the “vaults” of the Indian Arts Research Center which houses more than 12,000 artifacts and is open for viewing tours on Fridays by reservation. “During the summer, our busiest time, at least once a day I get a call from someone trying to find us,” administrative assistant for the Research Center, Daniel Kurnit, remarks, adding, “Sometimes they keep missing us, and I literally have to guide them in.” The complex is not small — it covers eight acres — but it is set back from the main road and built to hug the downward contours. “The fact that we’re secluded is part of the charm, but we really do want people to find us,” he laughs. Kurnit, who coordinates tours of the research vaults, notes that most public visitors come via word of mouth — a “you-must-stop-and-see” recommendation.

One such suggestion led Barbara Karp Shuster to the collection while visiting friends in Santa Fe. A board member of the Museum of Art and Design in New York City, Shuster’s area of expertise is contemporary African and African-American art. Her desire for a greater knowledge of Native American art, both historic and contemporary, brought her to SAR. “If you want to learn and have an understanding of Native American art, this is the place to go. The collection is phenomenal, and the ability to be shown around by a docent who has a love and enthusiasm for the work and then have it explained to you, is unlike any museum experience. The docents are available to answer questions and explain the different tribes, areas and languages, why and how they were affected by the areas and conditions. You really walk away with an understanding of what impacted the artists and their work,” Shuster reflects after a full morning in the vaults.

Shuster’s docent, Donald Thomas, first saw an article in the local newspaper saying that the School for Advanced Research was looking for volunteers to participate in their docent-training program. “I was new to the area and very interested in Native American art and culture. I was also looking for ways to meet people in the community,” says Thomas. The class of 30 immediately filled up and once a week for 22 weeks scholars, artists and collectors shared their expertise. “It was better than any course I ever had in graduate school,” he says. When asked if he indeed met new people through the experience, Thomas doesn’t hesitate. “Oh yes! I met the woman I’m going to marry this September!”

A docent for the past two-and-a-half years, Thomas explains with his subtle demeanor and expressive blue eyes SAR’s goal to link anthropology to the humanities. He shares the story about a class of Native American students who came to visit the collection with sketchpads and inquiring minds, prepared to record both ideas and designs. “It’s a living collection — the joining of the nature of spirit and the nature of materials. Therefore, they always refer to the pieces not as objects, but as subjects,” Thomas explains.

“The experience is very different than a museum visit,” comments Carolyn McArthur, the Collections Manager. “There are no windows or Plexi and visitors walk among the objects. People come to study the collection because it is so extraordinary,” she says. McArthur spends most of her time with the researchers, noting the responsibility to tribes and tribal members who are interested in learning more about their heritage. She remembers a Hopi who came to see the patterns from her tribe’s ancient artifacts, and a 17-year-old budding clay artist from Tesuque who wanted to study the shapes and artistic traditions of his pueblo’s “rain god” vessels.

Organized by language, the research vaults offer an extraordinary opportunity to see, first-hand, a pueblo’s subjects of antiquity side-by-side with their contemporaries. The Indian Arts Research Center collection is a valuable and priceless resource for connecting artists to their heritage and stirring deep and authentic inspiration for future work.

The Center’s grouping of San Ildefonso pottery is the most extensive outside the Smithsonian, explains McArthur as she reveals the legacy and some of the personalities behind the original collection. “Miss Amelia Elizabeth White [was] one of the original contributors,” McArthur says.

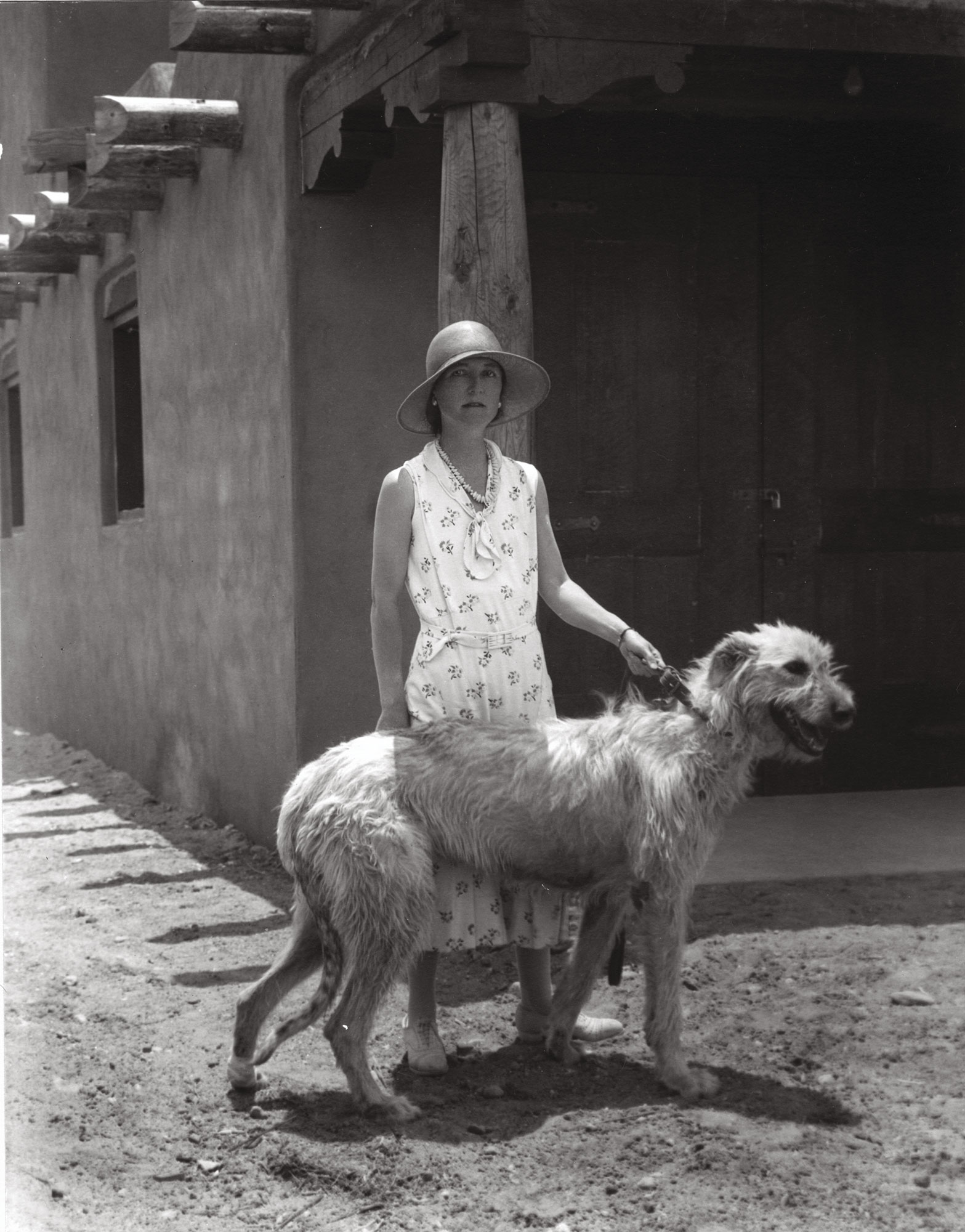

Elizabeth White’s name and the School for Advanced Research are intertwined and associated on many levels, the most obvious being that the SAR campus is the former estate of Elizabeth White and her sister, Martha, both of whom lay at rest on the campus.

The two sisters discovered Santa Fe in the mid-1920s during a cross-country trip from New York City to San Diego to view a solar eclipse. The story goes that the Whites, daughters of writer, newspaperman and financier Horace White, stopped in Santa Fe to have their hair done, and ended up moving to the community, becoming long-time supporters and patrons. Elizabeth and Martha had a lifelong passion for and made personal contributions to the health and welfare of the Native American tribes, the study of archeology and the patronage and support of Native American arts and crafts.

White organized the first exhibitions of Native American art in New York and Europe, and was a significant contributor to the Indian Arts Fund, initially named the Pueblo Pottery Fund. The Fund was organized in 1922 after a dinner guest at the home of writer Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant accidentally broke a Zuni pot. The legend is that the guests rushed to save the broken pot from being tossed into Tesuque Creek. The incident spurred an ongoing discussion about the troubles facing Native American potters: Pueblo elders largely responsible for creating fine pottery were perishing after a Spanish influenza epidemic in 1918; tourists were rapidly purchasing and carrying away pottery as souvenirs, depleting the pueblos of a visual connection to their heritage; and shifts in burial customs were contributing to the disappearance of work by contemporary potters. The founders of the Pueblo Pottery Fund recognized both the beauty and historic value, as well the decline of a tradition, and vowed to collect pueblo pottery to save it from extinction.

The scope of the Fund broadened in 1925 to include rugs, jewelry and other pieces and became available to anthropological researchers. The trustees of the growing collection also hoped that it would inspire Native people to revive their traditions. A crucial number of the subjects housed in SAR are from the original Indian Arts Fund collection, with a few hundred objects personally purchased and donated by Elizabeth White.

The White sisters’ estate “El Delirio” (translated as “the madness”) was named after a small bar in Seville that was near the hotel where the sisters stayed during a sightseeing visit to Spain. The Whites were continually lost in the winding and narrow streets of the barrio and would inevitably stumble upon the pub near their hotel. “Whenever we found El Delirio,” White would explain, “we knew we were home.”

The hacienda itself is significant to the history of Santa Fe as it is one of the first examples of the “Santa Fe” architectural style that was developed and refined by architects, principally by William Penhallow Henderson and John Gaw Meem, starting in the 1920s. The style evolved out of the philosophy that new construction should be built using traditional methods and materials, and be influenced by the shapes of the pueblos. Designed by Henderson, El Delirio would incorporate this design philosophy with a melding of Spanish Colonial and Moroccan visual modes while infusing a bit of New York chic. El Delirio quickly became a popular gathering place for Santa Fe’s dynamic community of writers, artists, anthropologists and archaeologists.

When Elizabeth White died in 1972, she gave El Delirio to the school, and the organization quickly filled all the buildings on the estate. The SAR Press is housed in the dog kennels, the board room occupies the stately living room, Dr. Brooks office is in the eclectic dining room and a highly competitive resident scholar program brings intellectuals to structures that once served as guest houses and an art gallery.

More than 175 Fellows have been hosted at SAR, including Kiowa Indian novelist and Pulitzer winner N. Scott Momaday, and noted poet and scribe Gerald Vizenor, to name just two among the lengthy list of esteemed talents including doctoral candidates writing their dissertations and full professors synthesizing years of research. “Our main focus,” Brooks emphasizes, “is to give our artists, scholars and writers a safe haven and a quiet, inspirational place to work.”

Elizabeth White hosted a number of artists at El Delirio and the tradition continues with the well-cultivated artists-in-residence fellowship ensuring a year-round presence of Native artists at SAR. The current Dubin Native American Fellow is a clay artist named Jason Garcia from the Santa Clara pueblo. Working to the sound of Johnny Cash and sporting a modern version of a 1950’s style haircut, Garcia works on his clay tiles which have garnered him both the coveted “Artists’ Choice” and “Best of Division” awards at the Santa Fe Indian Market. His pieces are created using hand-dug clay and harvested mineral pigments with age-old wood firing methods, but the imagery mixes themes and aspects of modern pueblo living. A kiln sits cold in the corner of the studio. “I’ve used it maybe twice, but the process left me feeling disconnected. I still prefer traditional methods,” Garcia says. In many other ways, however, Garcia has embraced technology. While scrolling through his MySpace page he explains, “I use computers for research, ideas and presentation.” He clicks on his tile image of Saint Claire, the patron saint of television, and talks about how the fellowship has given him the freedom and place to explore his ideas. “I think everybody says ‘I wish I had more time,’” he says, while acknowledging the support of the Dubins and other SAR benefactors.

The three fellowships provide a home and studio in which to work creatively and uninterrupted, and the program supports noted artists and their efforts to make significant contributions, as well as increasing public awareness of the individual artists. There has been multigenerational participation in the fellowships, and most of the artists’ work have achieved permanent homes in numerous museum collections including the Heard in Phoenix and the Denver Art Museum. “The experience really transforms their careers,” Brooks notes.

Walking through the intimate buildings and low-slung portals with intricately carved doors and squeaky hardwood floors, it is apparent that El Delirio and the School for Advanced Research is a place with deep roots, a strong history and unique personality. Even though both White sisters have passed, their presence is still felt around the complex alongside the scholars, artists and staff. In one of the offices, which was once Martha’s bedroom, a pigskin chair inexplicably rattles on a regular basis. Martha’s longtime friend and prominent archaeologist, Marjorie Lambert, often visited El Delirio and The School before her passing in 2006. Whenever a light breeze would wash over the campus, Lambert would off-handedly declare, “There goes Miss White!”

Indeed, the School for Advanced Research is the rare kind of place where you can expect to hear compelling ghost stories along with world-class lectures, all of them rich in history and texture. Behind the unobtrusive adobe walls, and in each of those stories, is hidden Santa Fe’s most beautiful and multi-faceted gem.

If you go …

Docent-guided tours of the Indian Arts Research Collections are conducted throughout the year every Friday at 2 p.m. Private and group tours may also be arranged with one month’s advance notice. Reservations are required for visitation and are $15 dollars per person. Illustrated and interactive lectures are held on the second Tuesday of every month. Memberships to the School for Advanced Research are available on an annual basis starting at $40 for an individual. For more information, visit the Web site of the School for Advanced Research at www.sarweb.org.

- El Dilirio, 1928.

- Resident artist Jason Garcia is known for his tile art. He works with natural pigments, minerals and clay gathered from around New Mexico’s Santa Clara pueblo.

- El Dilirio living room, 1928

- About 1,500 people annually visit the vaults at SAR, which are open to the public on Friday afternoons or by appointment.

- The White sisters had a love for animals and raised numerous Irish wolfhounds while they lived in Santa Fe.

- The dining room at El Delirio now functions as an office, but still maintains much of the original character, art and furniture from the White estate.

- Garcia works diligently in the Dubin studio preparing for the upcoming Santa Fe Indian Market.

No Comments