19 Oct Scouting the Terrain Ahead

I SEE MYSELF AS A ROMANTIC and feel as if I am a recorder or historian of some sort. I do a lot of experimentation in my work, but I want people, when they see it, to recognize it and know it is a part of this country and the Northern Plains Indian culture.”

Crow Indian artist Kevin Red Star is dedicated, in both life and art, to visually telling the stories of his people and the land they have resided on for centuries in south-central Montana.

Born in October 1943, Red Star is a preeminent figure in contemporary Native art.

His voluminous body of work — mostly in oils and acrylics, but also in print formats, pottery and other media — is found in museums and private collections around the world. He has been featured in several documentary films and PBS specials, is in demand as a speaker and presenter for the many charitable and educational organizations he supports, and is represented in galleries from Montana to Santa Fe.

Born into a large family of limited means, isolated on the sprawling Crow reservation amidst a culture that largely celebrated only the “cowboy art” of men such as Frederic Remington and Charles Russell, the path forward for Red Star was hardly paved in stone. But showing childhood talent as an illustrator, his initial steps toward an eventual career and success came when he was selected to join the first class at the fledgling Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe. Here he took his place alongside peers such as T.C. Cannon (Kiowa/Caddo), Doug Hyde (Nez Perce/Assiniboine/Chippewa) and George Flett (Spokane). Red Star trained under faculty such as Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache), Fritz Scholder (Luiseno), Lloyd Kiva New (Cherokee) and Charles Loloma (Hopi).

“I attach great importance to that first wave of artists who graduated from the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe a generation ago,” notes W. Richard West (Southern Cheyenne). West, founding director of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and current president and CEO of the Autry National Center of the American West in Los Angeles, goes on to say, “Lloyd New, the institution’s first art director, had a very particular dream — namely that Native art be a respected part not only of the life and culture of Native communities themselves, but also that a path be created to the larger international art movement and market for contemporary Native artists. Lloyd’s aspirations have typified Kevin Red Star’s career, as well as the professional journey of other artists of that era. They were the vanguard, and they accomplished it with great success.”

Red Star found his own way at IAIA, thanks to the breadth of the program and the instructors’ belief in their students. “They never said, ‘This is the style to follow.’ They introduced us to lots of varying, different approaches to art and art history, and let us find our own way. They didn’t know if we’d fall flat on our faces; they were taking a chance on us, that if they provided the tools and materials, the studios and instruction, we’d excel. We did,” Red Star says.

One of the non-Native art instructors at IAIA, James McGrath, worked with Red Star and recalls the artist’s innate talent. “Those early years were an incredible experience. It was like a family; everyone worked together. We talked a lot, we stayed up late and we went on field trips together. There was lots of freedom, lots. I remember Kevin once bringing in some samples of Crow beadwork (his mother Mary Bright Wings was a famed beader). I said, ‘See what you can do with this, but enlarge it.’ He did and I think it was a breakthrough — seeing things that were in your heart and in your DNA, but seeing it in a different way.”

In a letter written in 1965 to the San Francisco Art Institute, which Red Star subsequently attended, Lloyd New said of Red Star, “He is in the happy position of being able to tap his cultural heritage for many of his inspirations, coupled with ambition, industry and a quiet, gentle dignity. I predict he will be one of the outstanding painters in this country.”

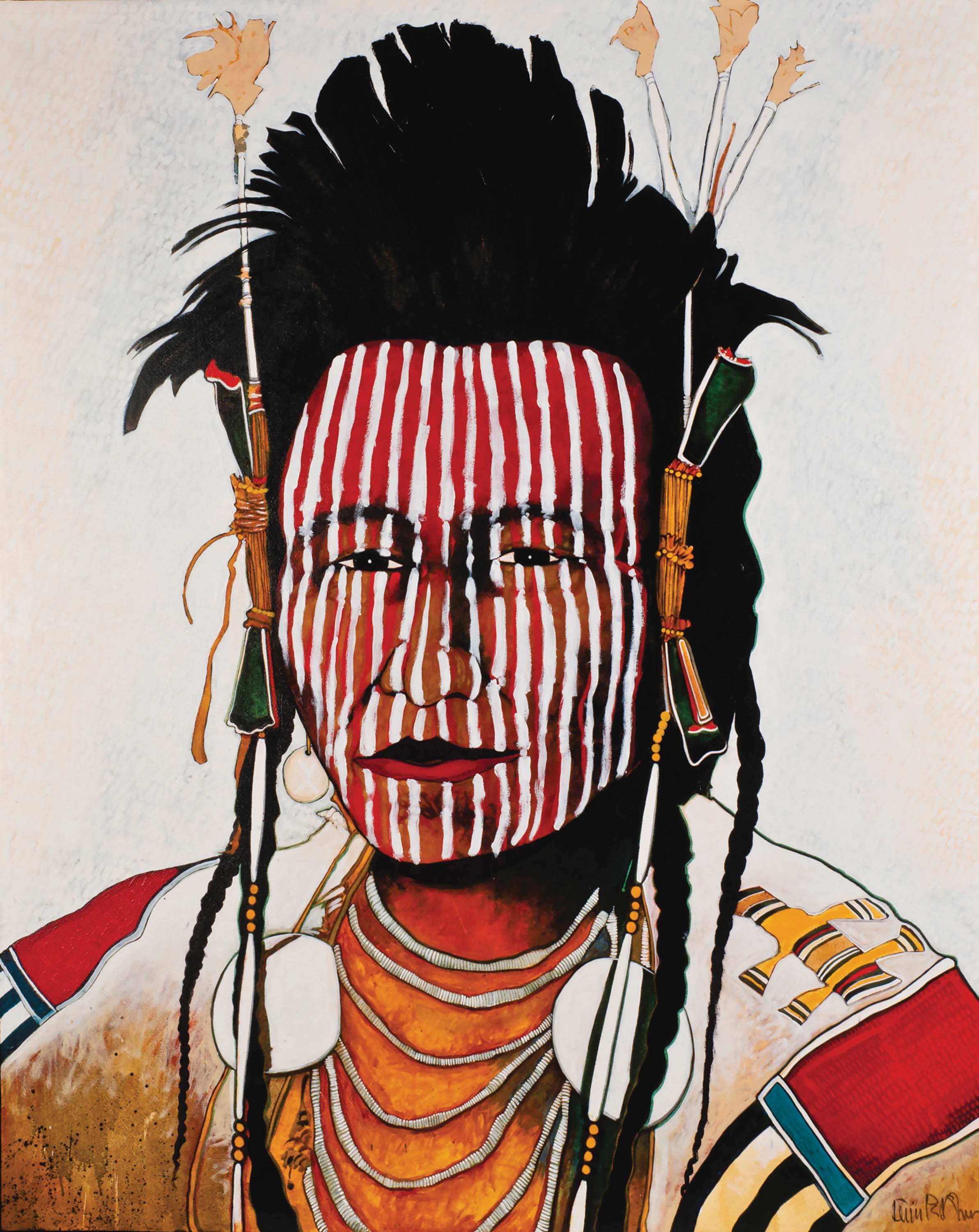

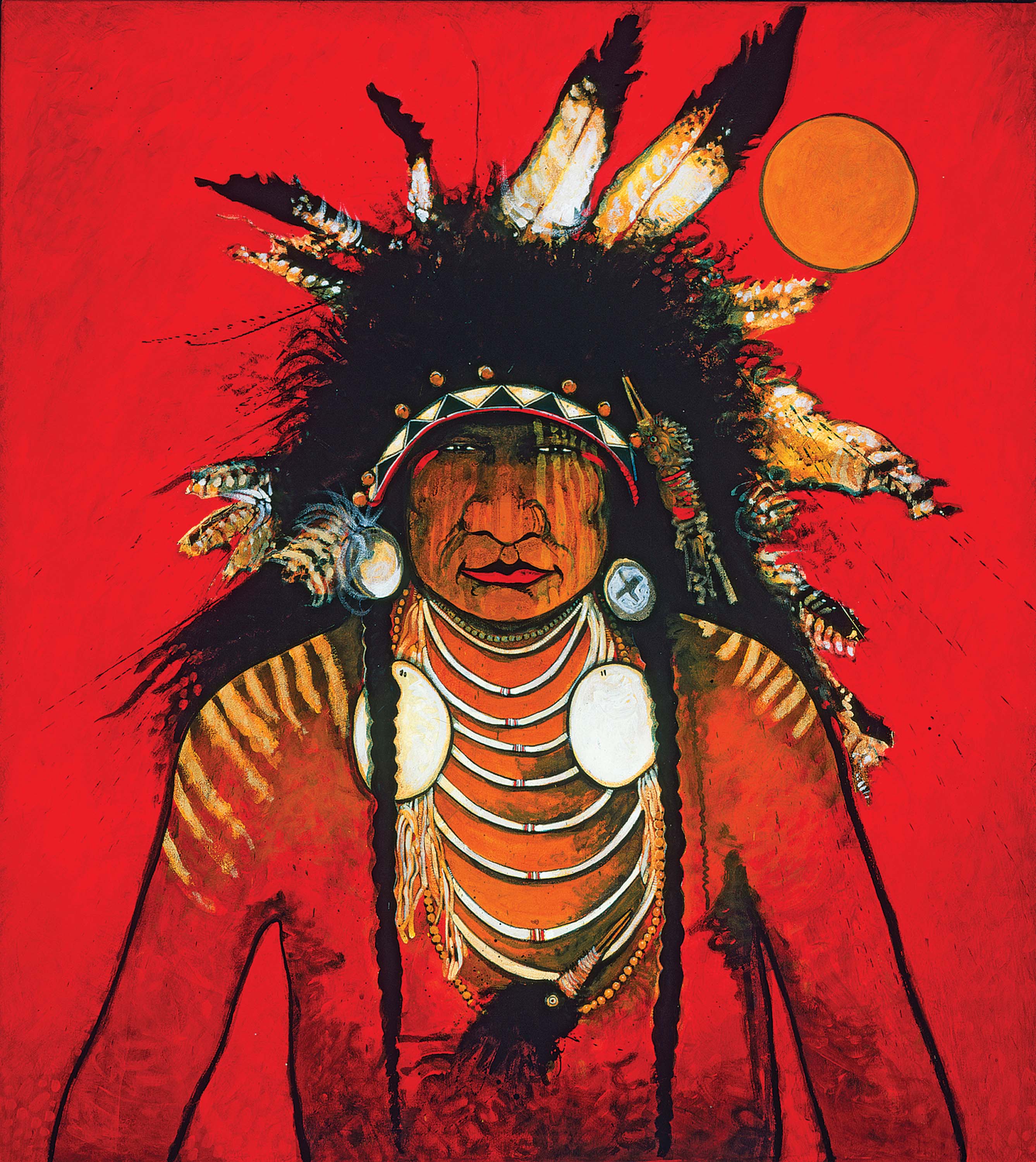

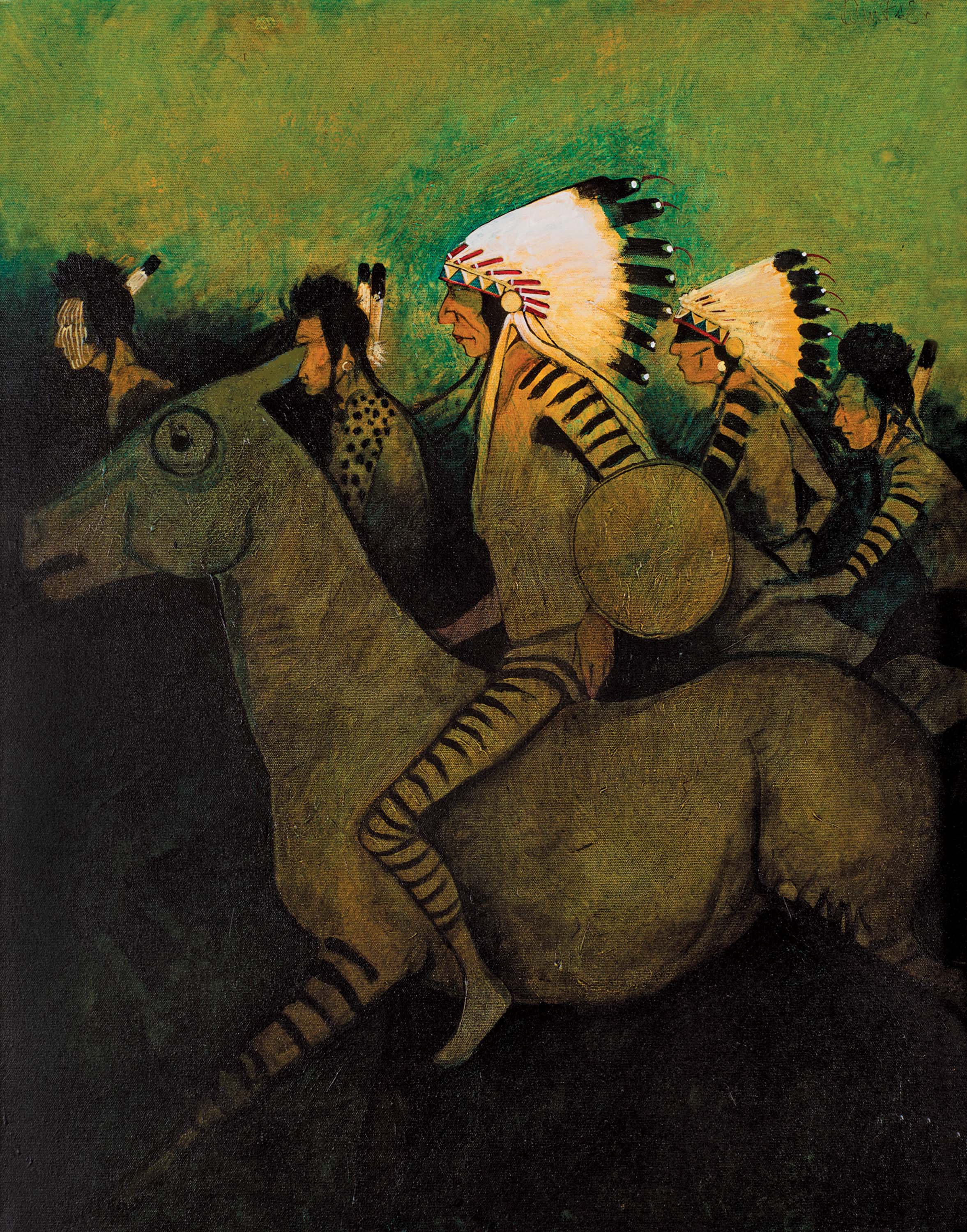

Indeed. Depicting the history of his tribe, their design motifs, their legacy as great horsemen and warriors, the intricate beaded garments of the women, their majestic tipi encampments, and other attributes of Crow culture became the life’s work of Red Star. Paintings such as Sundown Medicine Tipi are based on centuries – old scenes but abstracted and made new through the artist’s use of splatter technique, energetic brush strokes and alluring color combinations. In the late 1970s and ’80s Red Star’s portraits, such as Big Thunder, showed some distortion of facial characteristics, particularly in the noses, cheeks and hands of the subjects. But in the 1990s his portraits assumed the more naturalistic and realistic direction that he continues to refine and improve upon in his current work. One such example is Notch, a painting which some suggest is the very best of his career. Red Star once said to writer Michael Guilfoil, “I do exaggerate sometimes. But I never take it too far. I don’t want my art to be so outrageous that my own people can’t understand it.”

This attention to and concern for the opinion of his own people is perhaps the most dominant aspect of the artist’s life and career. “One of the strengths of his work is the combination of his personal experiences and his experience within his tribe, and how that blends with modern art styles and Native American art of the past and becomes something else,” offers Mindy Besaw, the John S. Bugas curator at the Whitney Western Art Museum in Cody, Wyoming, where several of Red Star’s works have been collected. “Graphically the images are recognizably his, but also very modern. Then if you dig a little past the immediate surface recognition, subject and beautiful design, it becomes something more.”

Decades ago, like one of the famed Crow scouts who crept over the horizon seeking a way forward for their people, artist Kevin Red Star ventured forth from his secure homelands to enter the field of fine art. He is still out there, forging a path.

- “Notch” Mixed Media on Canvas | 60 x 48 inches

- “Big Thunder” Acrylic on Canvas

- “The Night Charge” Acrylic on Canvas | 30 x 24 inches | 2013

- “Sundown Medicine Tipi” Acrylic on Canvas | 16 x 20 inches

No Comments