12 Nov Show and Tell

“BEING AN ARTIST IS ADULT SHOW-AND-TELL,” says artist Don Coen. And what Coen’s large-scale body of work reveals is a Western landscape peopled by hardworking men and women bound deeply to the soil — farmers, ranchers and migrant workers. It’s the daily West, not the romanticized West of old movies — no John Wayne or Tommy Lee Jones, just real people going about contemporary rural lives. Yet there is an eloquence in each painting’s portrayal of the dignity of labor, devotion to the land, and the people and critters that inhabit it.

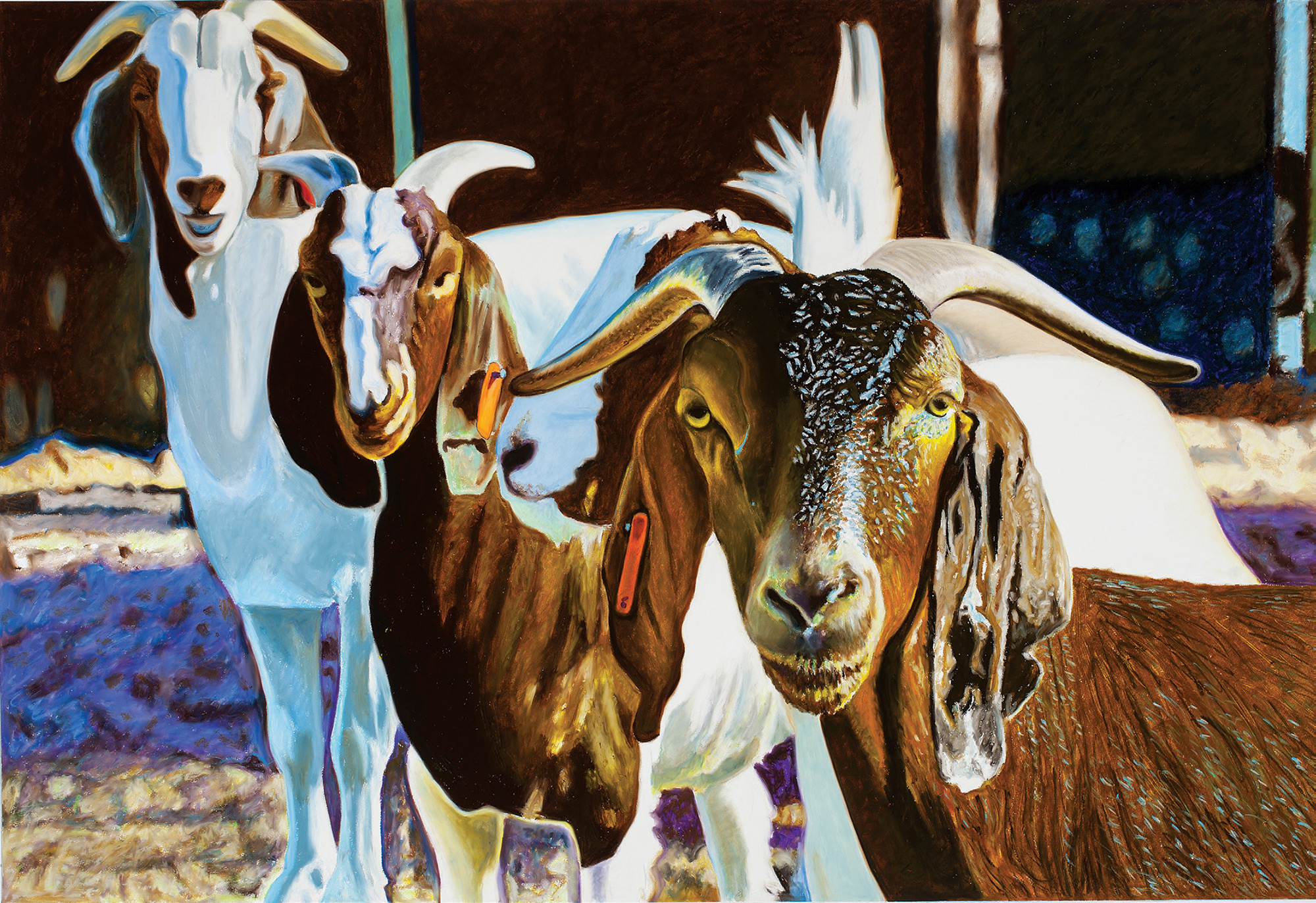

Coen’s paintings express an experience, as if the subjects are viewed through squinted eyes under a blistering sun, silhouetted and reduced to their quintessential elements. Day-to-day farm life; ear-tagged cattle; dogs, horses, hay balers and harvesters; hard-driven trucks; giant insectlike sprinklers; hogs; rattlesnakes; nights under vast, star-punctuated skies; and scenes so dusty they tickle your nose. Coen takes these elements and arranges them with his innate sense of design into profoundly satisfying compositions. If this is show-and-tell, Coen is the most fascinating kid in the class.

Coen’s West is a land he knows well. He was born and raised on the family farm in Lamar, Colorado. “I rode my horse every day, as many other kids did, to a nearby one-room school,” he says. At home, manual labor was a fact of life. “In the evenings, I would sit at our kitchen table and draw with a pencil on its white Formica top, blending with my finger, by the light of a kerosene lamp.” The family had no electricity or running water until Don was 15 years old.

From an early fascination in his teens with the traditional Western art of Charlie Russell, which honed his considerable drawing skills, Coen went on to a formal art education at the University of Denver, where he completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a teaching certificate and then, later, a Master of Fine Arts at the University of Northern Colorado. It was a period when he produced primarily nonobjective artworks.

Coen credits watershed moments with shaping the course of his long career. One such moment occurred in 1968, when he saw the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. Coen walked out of the theater knowing he would never paint the same way again. That night he created the first of what he calls his “religious symbolism paintings,” capturing abstractly the holy sense of a world beyond this earthly one. He began teaching himself how to use the airbrush, combining layers of it with traditional brushwork to provide the depth and radiance that have become signatures of his work.

In the early 1980s, another pivotal event drew Coen back to figurative subjects. He stood with a friend on a hill at Lake Neenoshe, north of Lamar, Colorado, staring into an evening sky “so beautiful that neither of us could speak.” His friend turned to him and said, “Don, you love this area so much; you should paint it.” And thus was born the idea for The Lamar Series.

Fifteen large canvases comprise The Lamar Series, each arising from a mélange of texture, pencil lines, pure white canvas, harmonious color work and about 60 layers of luminous transparent airbrushing. Their up-close, soft-focus character explodes with life as the viewer moves back to take in each composition as a whole. These scenes emerge from Coen’s understanding of a geography he’s been immersed in for eight decades and chronicles his reverence for contemporary rural life. Beneath immeasurable skies, people toil, have families, follow the seasons. Good crops and bad, rain or none, heat or snow, the seasons and their chores roll across the land in an unbroken cycle.

Few people today know the experience of waking at first light, stepping into a dew-fresh morning and gazing out over fields running in rows like an alluvial fan to the horizon. During harvests these views usually include clusters of workers bent to handwork, lifting and toting, loading and sorting. Coen’s latest work — The Migrant Series — was triggered by one such morning: “While in northern Colorado photographing a herd of cows, I saw some migrant workers sitting on burlap sacks of onions. The sun was streaming through their bandanas and I thought, ‘What a cool image!’” That moment set Coen on a 20-year path to photograph, document and paint migrant workers from California and Washington to Texas and Florida.

The Migrant Series consists of 15 large, closely cropped and intimate portraits of laborers in the fields of rural America. These paintings bring Coen’s life full circle. As a boy, he grew up doing hard manual labor every day and the Latino families that helped work their land were often well known to him as they returned season after season. Speaking of those days and the inspiration they provided, the artist says he “wanted to do a series of paintings to acknowledge what these men and women do for our country.”

In October 2014, The Migrant Series opened at the Phoenix Art Museum and drew record visitors. Curator Jerry N. Smith was struck first by the humanity of the workers portrayed, but was soon captured by Coen’s airbrush technique and the way he uses multiple layers of abstract patterns to create his images. “We were drawn in by the subject matter, fascinated with the artistry and technique, and came to see and think about a familiar subject in a new way,” says Smith.

The popular series has traveled to numerous destinations and, in 2016, can be viewed at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center and the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia.

Recognition and awards keep mounting for Don Coen. He is the featured artist for the 2016 Coors Western Art Exhibit and Sale, to be held this January in conjunction with the National Stock Show in Denver. Each year a committee headed by curator Rose Fredrick winnows down a list of talented artists to one whose work they feel uniquely represents the West.

“We are so pleased to feature Don Coen,” says Fredrick. “His roots are in Colorado and his art epitomizes what it is to be living and working in the region. He is a virtuoso.”

A remarkable visual historian, Don Coen reminds us through his inimitable style what America really looks like, the foundation of our abundance. He is now at work on a new series, titled Fly-Over Country, that will focus on events and scenes of Middle America.

- “Lamar Goats” | Oil Stick | 41 x 61 inches

- “The Harvest” | Oil Stick | 41 x 61 inches

- “T-Cross Mares” | Oil Stick | 41 x 61 inches

- “The Hunter” | Airbrush Acrylic | 6 x 8 feet | The Lamar Series

- “The Flock” | Airbrush Acrylic | 6 x 9 feet | The Lamar Series

- “Manuel” | Airbrush Acrylic | 7 x 10 feet | The Migrant Series

No Comments