_Above_Chamonix_36x38_Oberg.jpg)

04 Aug Soaring Visions

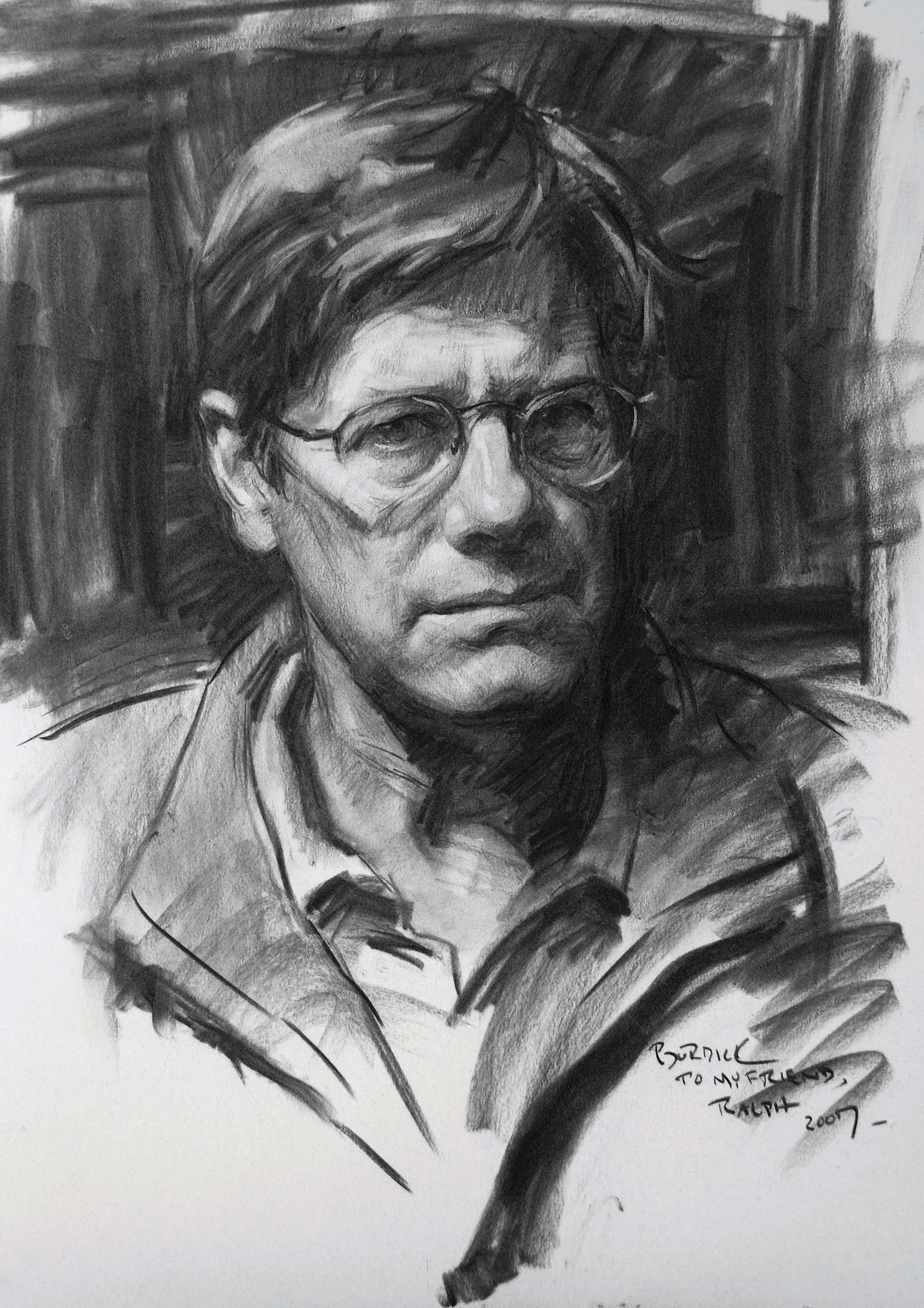

IN THE ANNALS OF ART HISTORY, Rembrandt is credited with stating it first, though the same observation is attached to Jackson Pollock: “Every good painter paints what he is.”

The pearl’s meaning is self-evident to most: Authentic artists are those forged by a magical blend of innate talent and gut-twisting instinct, an upwelling of mental imagination and curiosity and a constant craving for outside aesthetic stimulation that is absorbed into their being.

In the case of Ralph Oberg, there’s no mystery where his personal identity lies or what serves as the catalyst of his greatest inspiration. Oberg is a man of the untrammeled mountains, and the American landscape painter — from the West Slope of the Colorado Rockies — has, arguably, never been in finer form.

“Ralph is one of the few guys who really lives what he paints. Mountains are his sustenance,” says Matt Smith, who over the course of many years has joined Oberg in the field along with a group of noted artist friends that includes landscape painters Len Chmiel, Bill Anton and Skip Whitcomb.

This fall, Trailside Galleries in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, is hosting the biggest event in Oberg’s career: a one-man show titled The Mountain World — From The Himalaya to the Rockies: Works inspired by Ralph Oberg’s travels in Nepal, Switzerland, Alaska, Canada and the Western U.S.

For art collectors who reside in mountain communities, and even flatlanders who daydream of the crags where mountain goats, bighorn sheep, human mystics, hermits and intrepid explorers dwell, Oberg delivers soaring views from around the world. Where others might go hunting for stow-away artifacts in the garrets of old homes, Oberg has literally trekked into the attic of terra firma, and he’s carried back some astounding visual treasures.

Maryvonne Leshe, owner of Trailside, says the show quite literally represents a breath of fresh air. “After 35 years in the art business, I’ve seen the same kinds of themes repeated over and over again, but this one really is different.” She calls it international in scope and breathtaking in scale. “A lot of landscape artists get out on location, but for someone to reach all of these remote mountain areas and commune with the people and wildlife the way Ralph has, this show truly is unique,” she says.

Among the 20 major works in oil and smaller field studies, there’s something for every taste. The range of scenes includes glacier-fed lakes sparkling like emeralds in the backcountry of America, a colorful tapestry of prayer flags blowing in the wind beside a Buddhist chorten in Nepal and a shepherd ushering Valais blackface sheep into the pastoral Swiss Alps. Oberg’s been to each vantage. All his life, he says, he’s felt a connection to landforms that create jagged vertical horizon lines in the sky.

“I would describe this convergence of work as an apex moment for Ralph, a culmination of everything he’s been absorbing,” Smith says. “It’s an opportunity for people to see the mature work of a painter who has a novel perspective of the high country. He opens our eyes to a kind of beauty we know is there, but may not always register.”

In Above Chamonix, for instance, Oberg aspired to capture the jaw-dropping natural architecture found outside the French village that is a mecca for global mountaineers. “The sheer power of the verticality of the Aquille Verte and its subpeak, called the Dru, is astounding and humbling,” he says. “Elite rock climbers know the aspect for its hard routes, but what attracts them, what gives them and me pause, is the larger sense of grandeur.”

Born in Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1950, Oberg says his first four years of childhood were the only ones he ever spent at sea level. For nearly six decades, since his family resettled in Colorado, he’s never lived at an elevation lower than 4,800 feet.

“For me to be on a mountaintop is a metaphor for the fulfillment of total bliss and conscious awareness that nature provides,” he says from his studio in Montrose, Colorado. “Since the dawn of time, philosophers, prophets and seekers have gone to mountains for inspiration and answers. I hope my work speaks to those who have similar yearnings today.”

If Oberg’s work seems familiar, there’s probably a good reason. His landscapes/wildlife paintings hang in the House Chamber at the Colorado State Capitol Building in Denver and they’re in the permanent collection of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, and the Nature in Art Museum in Gloucester, England. His work also has appeared at the Prix de West Invitational, the Autry Museum’s annual Masters of the American West exhibition, the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s Western Visions show and the Coeur d’Alene Art Auction.

Certainly, every artist has a favorite coterie of historic predecessors. With Oberg, he makes a requisite mention of the French Impressionists, and influences in England such as J.M.W. Turner and art critic and essayist John Ruskin, who wrote, “Go to nature … rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing.” Oberg also has studied the works of members of the Hudson River School, such as Thomas Moran, who subsequently fanned out across the West making exaggerated paintings of the mountains to fit their romantic ideals.

Yet aligned most closely with Oberg’s personal aesthetic is a family of landscape painters, the Comptons, who made the mountains of Europe, namely the Alps, their muse and milieu. In particular, he praises the oeuvre of Edward Theodore Compton [1849-1921] who had an artist son, Harrison Compton [1881-1960], and two artist daughters. The English-born patriarch was a pioneering climber who spent his life painting and mountaineering around the globe.

After all, how many alpinists in history have expressed their joyous reverence on canvas? Answer: not very many. “Typically, artists tended to paint from the foot of the slopes with their heads tilted skyward,” Oberg says. “Edward Theodore Compton was a guy who understood the meaning of being on top because he made the effort to get there.”

Oberg’s affinity isn’t coincidental. He has spent a good part of his adulthood scrambling across the massifs of western North America on foot, from Denali and the Wrangell–St. Elias Range in Alaska to the Sierra and Cascades, and, close to his home and heart, ascending the Fourteeners of Colorado and the spires of the northern Rockies from the Wind Rivers to the Canadian Rockies.

Striking about the elder Compton and his son — who as a young man was stricken by polio that prevented him from reaching many summits — is that they both translated their pure love for the Alps with poetry and style, Oberg says. Another aspect of the Compton family legacy is that sisters Marion and Dora-Keel Compton painted mountain wildflower scenes, a passion shared by Oberg’s artist wife, Shirley Novak.

Novak recalls one of the couple’s research trips in which they followed in the footsteps of the Compton clan throughout the Alps. “When we landed in Zurich and took possession of our Renault Coupe, Ralph quickly learned how to drive like an Italian on the narrow and winding mountain roads,” she said, calling it hair-raising. “He drove to as many mountain vistas as we could pack into our month in the Alps. The excitement he felt as he experienced the same vistas that the Comptons had covered, as well as his time in the Himalayas, is evident in the body of work at Trailside.”

Oberg’s 32-by-54-inch Evening on the Eiger, a serene glimpse into warm evening light, is, in a way, an homage to the Comptons. Meanwhile, the 26-by-32-inch Om Mani Padme Hum is his allusion to the ancient Buddhist meditation on compassion. Oberg believes it has relevance in the 21st century. “It — Om Mani Padme Hum — is written in places throughout the Himalayan valleys,” Oberg says. “Over time, monks carved the mantra over and over on flat Mani stones by the thousands and placed them along the trails to benefit travelers.”

One could argue his paintings fulfill a similar function, but each piece aspires to convey the spirituality of its setting. With Ice Fall, this finished studio painting was inspired by a plein air study and is a view conceived in the Alps, but the artist says it could just as well be a depiction of pristine Nepal, New Zealand or Alaska. And, in the work The Enlightened, a mountain goat plays a metaphorical role, summoning thoughts of an old, white-haired mountain sage that imparts wisdom.

Oberg’s penchant for disappearing into the wilderness and listening to what the land tells him has been relentless. Within the last decade alone, he has accompanied painter Lee Stroncek on a 35-day trek, known as the Manaslu Circuit, in Nepal; made pilgrimages to the century-old vistas chronicled by Carl Rungius in the Wind Rivers of Wyoming with painters Tucker Smith, Chris Blossom, Clyde Aspevig, Carol Guzman and Jim Morgan; and headed into the Canadian Rockies with painter Randal M. Dutra.

“To meet Ralph is to appreciate a gentle soul who values hard work, good friends and is a true believer in all things wild,” says Dutra, recounting a trip when they packed camera, sketchpads and portable paints into Canadian roadless areas.

“We hit the colors in their full autumnal glory and the elk and other animals we were trying to find were there and in their rutting prime,” he says. The pair hiked Wilcox Pass twice — Wilcox being the rugged terrain that inspired some of Rungius’s well-known bighorn sheep paintings. “We found some bighorns and they were especially obliging and active, giving us the most tremendous poses and attitudes,” Dutra says. “Being in the mountains we were, not to exaggerate, closer to heaven, if not actually in it.”

Dutra says it’s those kinds of elements that flow through Oberg’s work. While best known for his portrayals of wildlife, Oberg approaches any subject with the philosophy of a plein air painter — the result of spending the last quarter-century in the company of talented artists positioned at the forefront of new Western Regionalism. “Life is not always a straight line from here to there,” Oberg says, citing a lesson he’s learned. “Often there are impasses and the retracing of one’s steps for a better route.”

Whitcomb describes the tranquil lexicon that Oberg articulates with a brush. “It’s a private, deeply personal, intimate language, a tribal one that defies words. To a layman, we might as well be speaking in tongues but you understand it when you see it,” he explains. “In the constant search for simplification, distilling things down to their pure essence, we’re after the importance of big shapes, and lost-and-found edges. For an artist like Ralph who delves into wildlife, the focus isn’t on feathers and fur. It’s always on identifying the power source of the bigger image.”

Trailside’s Leshe sees Oberg’s work as a vehicle for escape, a means for transport when a person feels stuck in the rat race. “All of our lives are so busy and hectic and consumed by technology. There’s a reason why art collectors are drawn to landscape paintings,” she says. “Ralph Oberg reminds us of the wilderness that is out there and the mountains where we want to be. When you spend time in front of his work, you can feel the stress leaving your body. He knows what life is supposed to be about: It’s about enjoying the beauty and peace of this planet.”

- “Evening on the Eiger” | Oil | 32 x 54 inches

- “Om Mani Padme Hum” | Oil | 26 x 32 inches

- “Ice Fall” | Oil | 12 x 10 inches

- “The Enlightened” | Oil | 34 x 44 inches

_Evening_on_the_Eiger_32x54_Oberg.jpg)

_Om_Mani_Padme_Hum_26x32_Oberg.jpg)

_Ice_Fall_Study_12x10_Oberg.jpg)

The_Enlightened_34x44_Oberg_copy.jpg)

No Comments