30 May Spirit on Canvas

“I give my paintings away,” says contemporary painter of Native Americans Jim Nelson. “I sell the spirit I paint into each piece.”

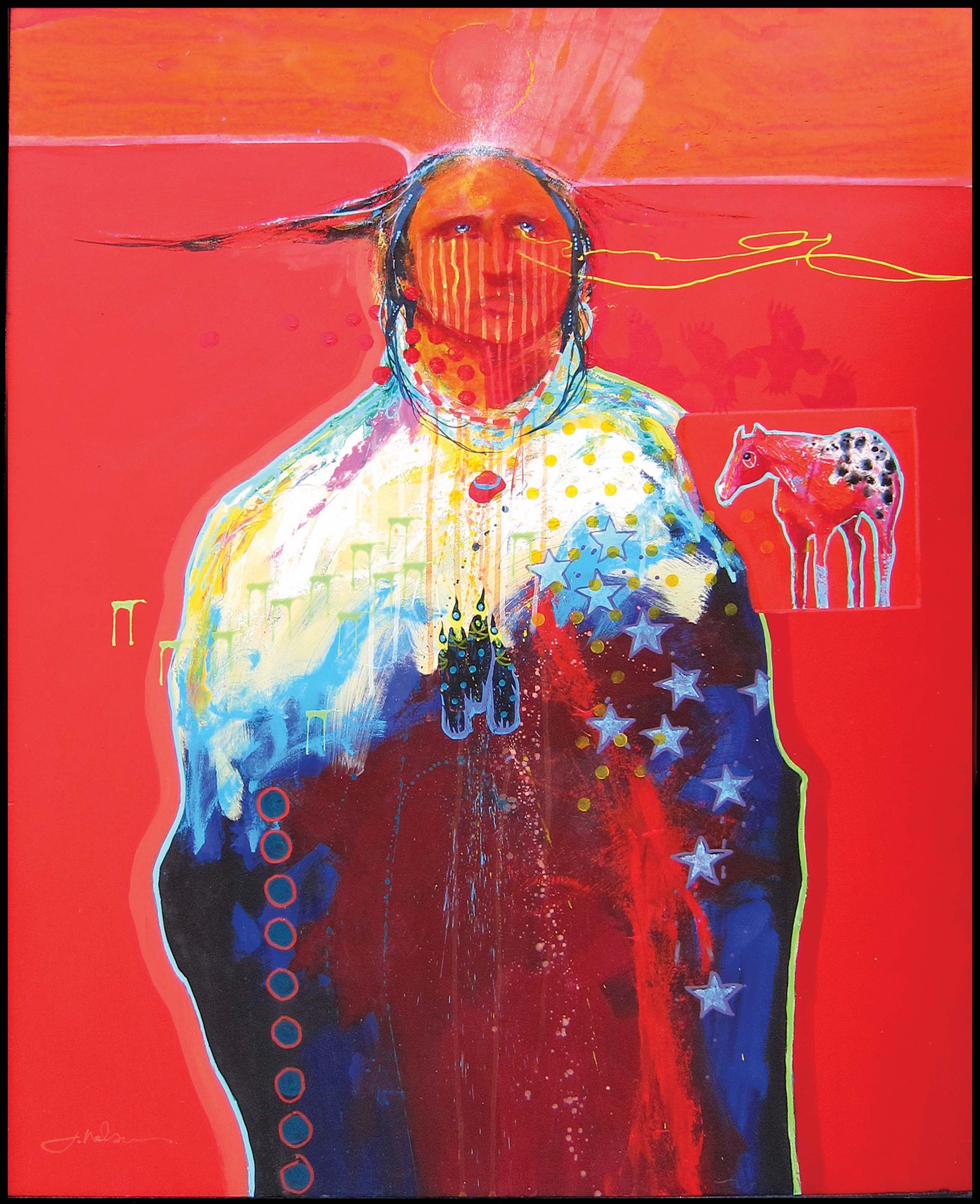

The comment may seem unusual, but to anyone who knows Nelson, agreement is unanimous. The vivid color he utilizes, the patterns and symbols he incorporates into a piece, and even the direction a subject faces has a spiritual significance deeply rooted in what the artist understands about the Lakota and Nez Perce Indian cultures.

Admirers also know only a portion of the finished Nelson painting is visible. Unseen under up to 10 layers of acrylic are painted symbols such as a medicine wheel or bear paw print integral to the spirit of each visual image.

Nelson’s passion and respect for the Native American culture is so deep, he is certain it is the spirit of what he paints that directs how he will render the image. “I paint the eyes first, and they impart what they want to see around them. The image flows out of my body into the brush and onto the canvas,” he says, acknowledging that the explanation may be difficult to comprehend.

He talks intently about being “pulled into a piece” to such an extent that he cannot talk or eat. “Once I am ‘in there,’ I cannot get out until I am done,” he says. When he finishes, Nelson often lays down on the floor, having spent all his energy transferring the spirit of his painting onto the canvas.

“I could talk about the symbolism and spirit and culture represented in one of my paintings for days,” he says. “Red represents the sun, blue represents Father Sky, green is Mother Earth, and yellow is the color of the cold stone, left after everything has been created.”

Nelson explains that a star represents wisdom. Checkered patterns stand for past generations, while a smaller checkerboard pattern signifies generations to come. Antlers on the headdress of a Lakota represent the deer that died to feed the hunter’s family. They have been placed there so the spirit of the animal can continue to look over the land and roam free.

“The spirit of my paintings cannot be contained,” Nelson says, explaining why his art flows off the edge of a canvas. It is also why he does not like a wide frame to surround his work. To ensure that his art is viewed the way he intends, Nelson adds a thin, quarter-inch black wooden border.

Nelson’s path to becoming a prominent painter of Native Americans had an inauspicious beginning. Diagnosed in childhood with dyslexia, and unable to contain his writing within prescribed lines, he was given crayons and blank paper. The freedom to express himself led to Nelson’s love of painting, which is an entirely self-taught skill.

He began to join his grandmother in South Dakota when she visited Indian reservations as a Christian Science missionary. There his fascination and respect for their culture was born. “I would just listen and talk to the elders, and attend as many ceremonies as I could,” he says.

Nelson learned to speak Lakota fluently and developed a close circle of Native American friendships. Eventually he was adopted by a tribal elder and given a Native American name.

After serving as a marine in Vietnam, Nelson worked in construction by day, but he always painted at night. He was unsure enough about his work that he hid paintings inside a closet until his daughter persuaded him to enter an art show where he won first prize. A juried show followed and a judge told Nelson that his was the only “real” art entered.

Realizing he might be able to make a living at what he loved, he began to paint full time.

For Nelson, seeing Native Americans identify with his work is a powerful reward. He tells the story of watching a man make a scooping motion toward his body, pulling the spirit of a painting toward him. For inspiration, Native American artist Amado Peña kept a Nelson painting on either side of his easel for years.

Others have questioned how Nelson can represent the Native American culture as a blue-eyed white person. “Merle Locke, the renowned Native American ledger artist, once asked me ‘Why do you paint my people?’” Nelson says. “I talked to him in Lakota about my knowledge and respect for his culture. Later he returned with a gift of a buffalo robe. It was a wonderful compliment.”

Today, at 71, Nelson lives on Whidbey Island, in Washington, with a panoramic view of Puget Sound and the Cascades out his studio window.

Prices for his work are at an all – time high, and Nelson enjoys a loyal following both with collectors and art galleries.

“Artists traditionally use color as an element in their paintings, but Jim has always been about telling a story with his colors,” says Betty Wilde, of the Wilde Meyer Gallery in Scottsdale. “We have prominently featured Jim’s paintings for 25 years.”

In the last three years demand for Nelson’s large paintings has surged. “We take as many large works as we can get,” Wilde says. Lois Zaroudny, of Milton, Washington, began collecting Nelson’s work 20 years ago. Today she owns 25 originals. “Visitors to my home have actually taken a step back the first time they see his work,” she says. “I know the story behind each piece and it elevates a collector’s appreciation to a higher level.” Her sentiment is exactly what Nelson wants to achieve. “If my art ‘speaks’ to you, I have accomplished what I set out to do,” he says.

Zaroudny expresses her sentiments differently. “Someone would need to kill me and my dog before I would let my Nelsons out of my house,” she says.

- “Ghost Shirt Series #2” | Acrylic | 48 x 38 inches

- “Urban Hunter” | Acrylic | 40 x 48 inches

- “Sun Dog” | Acrylic | 28 x 48 inches

- “Yellowhead Speaks to the Old Woman” | Acrylic | 36 x 30 inches

No Comments